Sign up for the

TSL Newsletter

and get $50 off Final Draft 12

By Patrick Kirkland · June 16, 2011

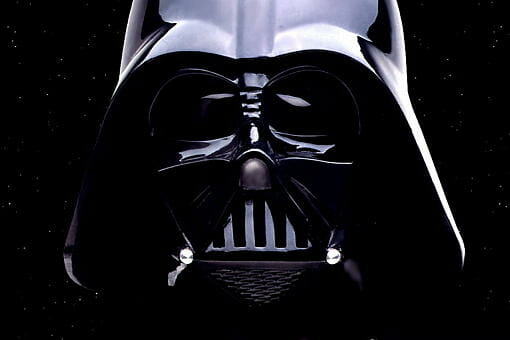

Darth Vader. Gollum. Hannibal Lecter. The Wicked Witch of the West. Wherever you find a Hero’s journey, you shall, or at least you should, find an even greater Villain trying to block the Hero’s path.

This is the second key of writing a great story. The Hero’s objective must breed opposition in order to produce conflict. In your screenplay, you may have the perfect hero. The perfect character. The exact right amount of comedy, drama, and romance. You may have the perfect role for Meryl Streep or Jack Nicholson, but you’ve got nothing if you don’t have those opposing forces.

While you’re writing, ask yourself this. What’s going to keep your Hero from completing her quest? Who (or what) is going to push against her, force her in a corner, and squeeze her to act, to do something, for better or for worse, to rise above, to overcome, to survive?

Think about it like this. Screenwriting, story telling, even life, is a massive event between force and counter-force. Your Hero’s objective will lead your protagonist(s) onto his or her path. The quest to return the ring. The trip down the yellow brick road. The desire to save the Empire. But as much as you put into that objective, that spine, you have to put just as much, if not more, into keeping them from achieving that goal. Your Hero wants to return the ring? Fine. Write in entire armies, floods, and Wizards that get in their way to kill them before they arrive. Your Hero wants to follow the Yellow Brick Road? Great. Swarm it with flying monkeys. Your Hero wants to save the Empire? Cool. But the there’s also a Dark Empire that wants to kill everything you’ve worked for. Oh, and the Leader of the Dark Side is also the Hero’s father.

In trying to achieve the goal, your heroes must have to fight with every inch of themselves; they must reach the end of their limits. They must travel the depths of their souls. How is a character supposed to do that without opposition? Frodo would not have learned the true meaning of friendship from Sam Gangee if he had not had Gollum pushing his every move. And would George Bailey have learned that it’s a wonderful life without Mr. Potter stealing all of the bank’s money? No. Hell no. Without Potter’s schemes, Bailey would have never considered suicide, and would have never learned the meaning of real happiness.

Heroes must feel pain. And not just like normal pain, not just sadness. Pain. Real. Honest to God pain. They must all, like dear Mr. Bailey, consider suicide in their own way. And they get there by the story’s opposing forces giving them no choice but to dig a little deeper, muster up a little more, and push through. The pain must almost kill them. Think about Oskar Schindler falling to his knees, crying, “I could have saved more.” Think about Marlin the clownfish swimming away after he thinks that Nemo has been killed. Or even Maximus being stabbed in the arena. He must consider – must move towards – must decide, for the moment, that he will give up. Because if he doesn’t think about giving up, he can’t think about how the hell he’ll muster all his strength, all his energy, and every bit of his soul just to get back in the fight and win the battle for one last time. He must kill Commudus.

Don’t be afraid to pull out all the stops, as long as you do it organically. Sure, it would have been a lot easier to end Marlin’s journey by Michael Bay’ing it with a handful of grenades and a rocket launcher, but it doesn’t exactly fit with the story. It doesn’t fit with the theme, the genre. Hannibal Lecter could have eaten Clarice Starling’s liver with some fava beans and a nice Chianti. And what if 12 Angry Men’s Juror #8 decided to end deliberations by stabbing all the other jurors with that knife? While you’ve got a whole world of options in front of you to push your characters, it’s the opposition – the villains, the conflict, the obstacles – in the world of your story that makes it work. While Finding Nemo has AA meetings for sharks, proclaiming “fish are friends, not food,” Jaws wants you to believe that sharks will eat anything in their path, including humans. In that world, everything’s food.

In order to maintain the maximum opposition possible, apply the percentage plan. If your Hero is 10% into their journey, come back at them with 15% opposition, and see what happens. If you’re Hero is just rounding the 50% mark, push back with a 60% obstacle, and make them feel really uncomfortable. And if they’re 90% of the way there, go ahead and unleash Hell.

To learn more about The Hero's Objective read Part 1, The Spine and Part 3, Connection.