Sign up for the

TSL Newsletter

and get $50 off Final Draft 12

By Martin Keady · September 19, 2016

“Round up the usual suspects.”

This classic line from Casablanca, delivered by the cynical Captain Renault (played by Claude Rains) near the beginning of the film and also near its end, has haunted me while trying to write these pieces on “The Great Screenwriters”, because all too often I have felt that I am only focusing on “the usual suspects”– the most famous and celebrated screenwriters of the past, who are invariably dead white males. I have sought to uncover less famous, less celebrated screenwriters and in particular the women and black and other ethnic minority screenwriters who have been largely overlooked in considerations of cinematic history. However, the truth is that up until the 1960s the overwhelming majority of screenwriters, both in Hollywood (the largest film industry in the world) and elsewhere, were middle-aged men, and consequently finding unknown female or black or other ethnic minority screenwriters has proved a largely thankless task. Moreover, it is easy to forget that so many of those white male screenwriters were themselves members of a minority (in the world at large, if not in Hollywood), because they were Jewish. Their ethnicity and even their own experiences of anti-Semitism often informed their work, if only obliquely, and no more so than in the example of Casablanca itself and its principal writers, the Epstein brothers, Julius J. and Philip G.

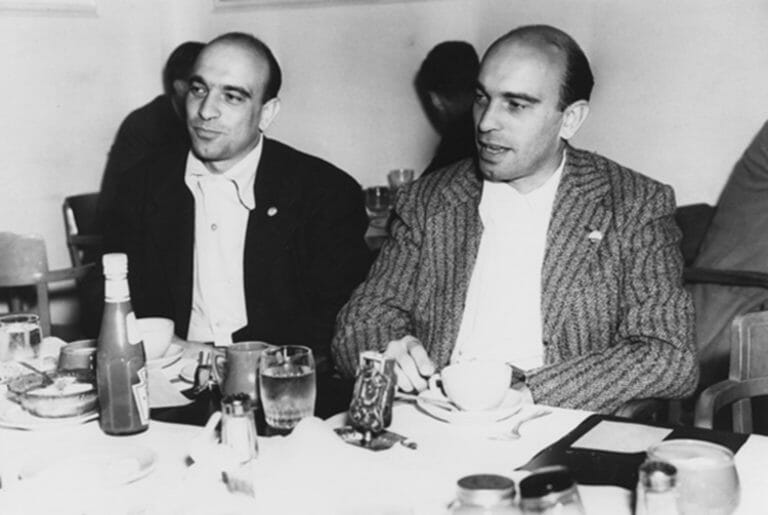

The Epstein brothers were not just brothers; they were twins, and identical twins at that. It is often thought that identical twins have some kind of intimate mutual understanding, even telepathy, and that certainly seems to have been the case with the Epstein twins, who ended up writing scripts together.

Like so many of their Hollywood contemporaries in the 1930s and 1940s, such as Ben Hecht and Herman J. Mankiewicz, the Epsteins originally hailed from New York. In fact, so many of Hollywood’s finest writers of the period hailed from the Jewish community of New York that at least one studio executive took to referring to it as “Jew York”.

The Epstein twins were born on 22 August 1909 and the fact that their parents ran a livery stable in Manhattan, at a time when there were still more horses than cars in the city, is a reminder that the NYC they were born into was not quite the teeming metropolis it is today but rather the host of a dozen or more significant ethnic communities, from the Italians to the Chinese to the Irish. It is a world brilliantly recreated by Francis Ford Coppola in The Godfather Part II, when Robert De Niro’s young Vito Corleone assassinates a local mobster before escaping over the tightly packed rooftops of Little Italy.

Always close, the Epstein twins both studied at the Pennsylvania State University, graduating in 1931 and heading almost immediately to Hollywood to try to pursue a career writing for film. Like so many would-be screenwriters of their generation, they were probably led West by the kind of thinking that lay behind Herman J. Mankiewicz’s famous 1926 telegram to Ben Hecht, which read: “Millions are to be grabbed out here and your only competition is idiots…Don’t let this get around.”

The Epsteins may not have made “millions” initially, but they certainly found work, initially working apart from each other. Julius was the more successful of the two, earning a nomination for an Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay, alongside Thyra Samter Winslow, for his work on Four Daughters (1938). The film was based on Frances Hurst’s novel, Sister Act, and told the story of four sisters whose successful singing careers are nearly derailed by their unwise choices of men, including a cynical composer who hopes to exploit their musical ability.

Undoubtedly boosted by this official recognition of his writing ability, from 1939 onwards Julius increasingly collaborated with Philip. As was so often the case in Hollywood at that time, the brothers would undoubtedly have worked on at least some scripts without receiving official recognition, working as “script doctors” to fix unwieldy or problematic screenplays in a manner that continues to this day. But they finally found fame and considerable fortune when they were hired to adapt an unpublished – indeed, unproduced – Broadway play by Murray Bennett and Joan Alison. It was called Everybody Comes To Rick’s, but it would be renamed for the big screen as Casablanca.

The writing – indeed, the entire creation – of Casablanca has become one of the great movie-myths, in which (in true Hollywood style) it is virtually impossible to disentangle reality and legend. What is certain, however, is that Casablanca undoubtedly benefited from an impeccable piece of timing. Warner Brothers acquired the rights to adapt the original play early in 1942, soon after the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbour in December 1941 that eventually prompted America to enter World War Two. There was suddenly a rush to produce films about the war and particularly American involvement in it. Everybody Comes To Rick’s would have been one of the dozens of plays, novels and other stories acquired in that frantic gold-rush (“celluloid rush” would be more accurate), but unlike almost all the others it would not only be made but would go on to become if not the best movie ever made then almost certainly the most beloved.

The Epsteins were originally hired as the sole writers of Casablanca, but after beginning work they almost immediately left Hollywood to work with the great director Frank Capra on his series of patriotic (i.e. propaganda) films, Why We Fight, which they obviously felt was more important than the “corny” melodrama (as Philip initially described it) of Casablanca. In their month-long absence, the film’s producer, Hal B. Wallis, hired another writer to work on the script without the Epsteins, Howard B. Koch.

The tangled, even tortured creation of Casablanca, especially its screenplay, is comparable to that surrounding the writing of one of its greatest rivals in the “Best Movie Ever Made” stakes, Citizen Kane, which was made just a year earlier in 1941. Just as the great film critic Pauline Kael would argue in the 1970s that the true creator of Kane was the man who wrote its first draft, Herman J. Mankiewicz, so Howard B. Koch would go on to write a couple of books about his contribution to Casablanca, a contribution that the Epsteins always belittled, with Julius in particular maintaining to his death in the year 2000 that not one of Koch’s lines had been used in the final film.

Such was the confusion surrounding Casablanca, as it went through several possible directors before Michael Curtiz was finally drafted in to see it to conclusion, that other writers were allegedly involved in the script, including the uncredited Casey Robinson. Indeed, it has even been claimed that the film’s famous last line (often regarded as the most famous last line ever written), “Louis, I think this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship”, was written by the producer, Hal B. Wallis, himself, as the ending of the movie was hastily re-edited after early test screenings to try and make Captain Renault’s eventual discovery of his own humanity more credible and believable.

Of course, despite the uncertainty surrounding its original creation, Casablanca has gone on to acquire classic status; indeed, it did so almost from the outset, as it went on to win three Academy Awards, including the Best Adapted Screenplay for the Epstein brothers and Koch. To this day, nearly eighty years on, it remains one of the greatest screenplays ever made and, I would argue, the only screenplay (other than Withnail and I) that is totally quotable, i.e. every single line (even the shortest and seemingly most innocuous) is quotable. The Epstein brothers were often mystified by this success, with Julius famously saying that the script had “more corn than in the states of Kansas and Iowa combined. But when corn works, there’s nothing better.”

That typically self-effacing description of their contribution does not do justice to the Epsteins’ work (alongside that of Koch, Robinson and Hal B. Wallis) on the script of Casablanca. It is ironic that they initially broke off from writing the screenplay to contribute to a series of propaganda films, given that Casablanca itself is probably the most perfect and, more importantly, effective piece of pro-war propaganda ever made. It is, of course, impossible to quantify exactly what effect, if any, the success of the film had on mobilising American support for the war, but it is equally undeniable that the fact it won Oscars for Best Picture, Best Director and Best Adapted Screenplay was a testament to America’s growing appetite for involvement in what it saw as a “just war” against the evils of Nazi-ism.

I can cite a personal example of the enduring power of Casablanca. In June of this year, I was watching the opening match of the 2016 European Championships in France in a bar in South London, which was occupied by a large number of French people who had come along to watch their national team open the tournament. As the Marseillaise was played at the beginning of the match, every French man, woman and child in the pub got to their feet to sing along, in a moving demonstration of patriotism, especially in the face of the “new Nazis”- so-called Islamic State – who have wreaked so much havoc in France over the last 18 months. As my wife said at the time, “It’s just like being in Casablanca.”

Unsurprisingly, Casablanca proved impossible to top for the Epstein brothers, especially when Philip died of cancer in 1952, at the early age of 42. Unsurprisingly, his brother Julius was devastated and although he continued to write screenplays, including The Tender Trap (1955), a romantic comedy starring Frank Sinatra, and Send Me No Flowers (1964), one of the many films starring Doris Day and Rock Hudson, it is arguable that he did not write another truly great screenplay until nearly forty years after Casablanca. That screenplay was Reuben, Reuben, which was filmed in 1983 and starred Tom Conti as Gowan McGland, a poet who is a thinly disguised version of Dylan Thomas. Like Thomas, McGland is a Celtic poet adrift in the commercialised, suburbanised America of the 1950s, who eventually accidentally kills himself. The kind of grim humour that Reuben, Reuben is full of is also a characteristic of Casablanca, in which a cynical police chief can announce whenever there is a murder, “Round up the usual suspects”.

Julius eventually died in 2000, nearly fifty years after his brother had passed away, and if in the end the only truly great screenplay that they wrote together (albeit with the possible help of unwanted collaborators) is Casablanca, then that is enough for any writer (or team of writers). Their marvellous screenplay has received the ultimate accolade, in that it has become the inspiration for several other critically acclaimed and commercially successful movies and television programmes, from Woody Allen’s Play It Again, Sam, in which Woody plays a neurotic film critic who receives lessons in love from “the ghost of Bogart”, to the classic episode of Frasier where Frasier rushes to the airport to try to stop the woman he loves from leaving Seattle, only to discover, while they wait for the plane, that they are actually utterly incompatible. In this way, Casablanca has become one of the very few movies that have escaped the screen entirely to become part of the wider culture and, ultimately, part of life itself.