By Pam Glazier · April 9, 2012

I was excited to see this small Italian film the moment I first saw the trailer. It looked like it would be a light hearted and respectful romp through the Vatican. A sort of religious Mary Poppins or Il Postino… you know, heartwarming. And beyond that, I was happy to see a film that seemed to be thoughtful and considerate in respect to spirituality, belief, and religion. There are so many movies out there these days that seem to employ a not so subtle iron-jackhammer approach to insinuating that an anarchy of belief is the only thing that won’t destroy your humanity—i.e., these days, in some of the more simplistic cinematic narratives, churches are as good as Nazis or warlords (Priest, or any of that schlock based on those horrid Dan Brown novels). But to get back to the point, it was a novelty to see a film that suggested that spiritual leaders care about the wellbeing of their parishioners.

It was because of all of the above that I was so saddened by this film. You see, it sucked. It was long and tedious and the overly abstruse narrative left me feeling like I didn’t get it, like I wasn’t high-brow enough. But come on! That isn’t possible. I use words like “abstruse” for God’s sake! But there I was, scratching my head, trying to figure out how the plays of Chekov, an international Volleyball tournament between cardinals, and the field of psychoanalysis could possibly come together as a cohesive unit in order to either literally or metaphorically correlate to modern day problems of religiosity. I’ve been ruminating on it for a week, and I still can’t come up with even a semblance of a logical argument that would hold up against scrutiny.

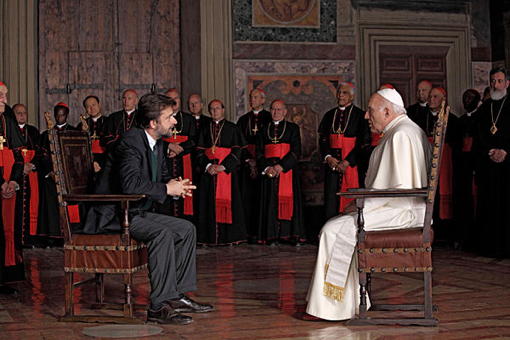

By this point, you might feel like asking me what I am babbling on about. Well, here’s the film in a nutshell with the ending excluded, just in case you want to slog through it. (SPOILERS) The Pope has died and so a new Pope must be elected. Unfortunately, the new Pope (Michel Piccoli) cannot bear to face the world. He screams and hides at the thought of greeting the masses awaiting his first speech. The cardinals try and give him encouragement, but he cannot be persuaded. So a psychoanalyst (Nanni Moretti) is called in. But alas, the psychoanalyst has no luck as well. For secrecy’s sake, the psychoanalyst is kept in confinement until the Pope decides to assume his divine duty. The new Pope tries a second psychoanalyst (Margherita Buy) outside the Vatican and escapes the motorcade during this outing. He then wanders the streets of Rome and eventually begins living with a troupe of actors who put on Chekov plays—one of these actors has a mental breakdown and madly recites his lines as if they were his own. The cardinals are lied to about the Pope’s absence in order to keep them calm and in the Vatican. It is during this time that the psychoanalyst decides to organize the volleyball tournament. And so we are left with a series of questions. Will the Pope find it in himself to return to the Vatican? If he does, will he assume his role? What does Chekov have to do with any of this? And above that, what the hell does volleyball have to do with any of this? And who won the tournament anyway? And does that have anything to do with anything?

By the end we do learn what the pope decides to do, but the Chekov/volleyball/psychoanalysis questions are left bafflingly wide open. I got the sense that I wasn’t Catholic enough to get it, or that I wasn’t Italian enough to get it. And it is because of these confusions that I sadly must denounce the writing of this film. The scenes were good, but they had no substance as a whole. It felt like there was some grander metaphor going on that never seemed to land.

Thus the only reason I would ever suggest this film is for the acting and technical attributes only. The shots of the Vatican were lovely. And the acting was well delivered. If you want to see what a film that despite being comprised of decent scenes manages to fail as a whole looks like, then watch this. There were several, if not many, wonderful scenes that wandered around like poor starving orphans trying to find their way home. Take this as a grave writer’s lesson—from time to time, you’ve got to stand a few feet back from your canvas and squint so as to ensure the composition works not just in its component parts, but as a whole as well.

And if you’ve got some sort of genius insight that links volleyball and Chekov, please do correct me. It would be fascinating to learn about the deeper meaning that I missed.