By Nguyen Le · April 8, 2015

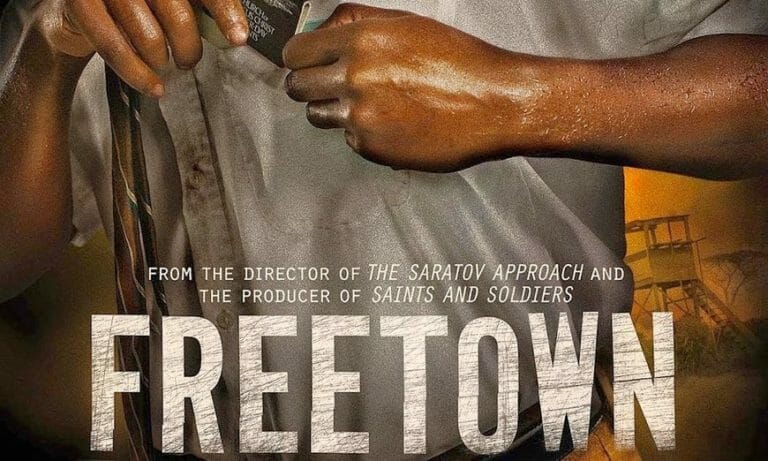

Director Garrett Batty’s latest outing marks a revisit to fact-based and faith-centric storytelling. Mormon missionaries are at risk again, but this time in Africa and in an exclusively local situation. As a film with a religious message, Freetown scores. As a film, this genuine effort has a few rough edges.

For a foreign place becomes a beacon of safety, one’s situation has to be really dire. The year is 1989, and Liberia is in chaos when a rigged election that has placed the Krahn tribe in power ignites a civil war. Rebels are killing anyone who are, or in support of, Krahn. As a result, Elder Gaye (Phillip Adekunle Michael) is in danger and cannot stay in the country. Determined to stand by one of their own no matter what, the other Elders – Nyanforh (Clement Amegayie), Forkpah (Great Ejiro), Meyers (Alphonse Menyo), Menti (Michael Attram) and Sellie (Bright Dodoo) – also pack up, squeeze into the small Toyota Corolla driven by local church leader Abubakar (Henry Adofo) and flee to Sierra Leone’s Freetown.

By now with “based on true events” films, audiences might go “yeah, right” from the outset. For Freetown, however, they will likely reserve or eliminate the notion thanks to the film’s effort in making every aspect so grounded, so honest. Accra, Ghana stands in for Liberia, but every scene is shot on location. The performers on screen? All are local. Surrounding these welcoming details are director of photography Jeremy Prusso’s thoughtful framing choices, Robert Allen Elliott’s stirring score that mixes African chants with a bit of Harry Gregson-Williams, effective use of sounds, the occasional smart dialogue and powerful sequences from Melissa Leilani Larson and Batty’s script.

Unfortunately (and interestingly), each of the aforementioned pros manages to show its other side as well. The music appears in scenes where silence is the better choice. Certain moments, sweat-inducing or enlightening, have their effect ruined instead of realized, heavy-handed as opposed to natural. The actors playing the Elders are better when together; in their isolated sequences their performances range from acceptable to questionable. Extras, on more than one occasion, smile when they are not supposed to. Also worth noting are a bizarrely staged nighttime supply-gathering sequence, Batty’s tendency to include an overhead shot – some welcoming, some arbitrary – and the screenplay’s close brushes into preaching territory. The latter is made worse when the wording, from two Utah writers, is perhaps too complex for our performers; it is difficult to make out what they say at times (if not due to this then it is the overpowering music).

The largest issue, nevertheless, is this: Batty’s straightforward approach. On one hand, this is ideal as it steers the film from Hollywoodization and makes moments of drama (ones without distractions) and humor click better. On the other hand, the sincerity breeds more than a couple of snails in the film’s pacing when, from reading the plot alone, they have every right to expect a fast-paced, tension-all-around journey before the theater lights go dim.

Despite being a refreshing entry in the religious film genre because it avoids exaggeration or constant belief-affirming/questioning moments, Freetown has flaws in its craft that have viewers enjoy at one point and perplexed the next.

Ultimately, the film provides a torn experience upon watching as its “no surprises” nature means “where is the entertainment factor,” but all the investment – creative and otherwise – is so true you are bound to find the film endearing.

Trailer Credit: Three Coin Productions & Go Films