By Martin Keady · June 2, 2017

The Story Behind The Screenplay is a new series by Martin Keady that examines the origins of some of the greatest screenplays. It continues with the story behind arguably one of the greatest (or at least most quotable) screenplays ever written – Withnail and I.

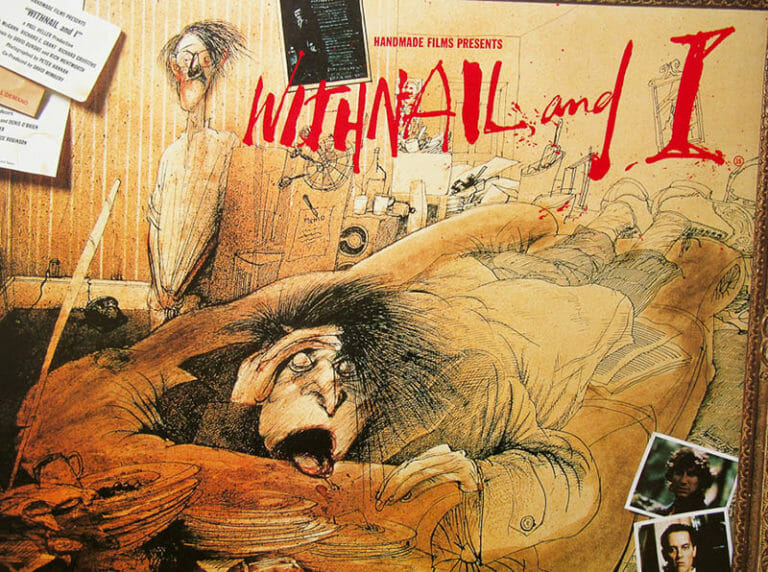

Withnail and I, Bruce Robinson’s autobiographical and magisterial film about the lives of two struggling actors in late Sixties London, has completed the rare cinematic journey from cult movie to acknowledged masterpiece. On its release in 1987, it was far from a box-office triumph, but as word spread (particularly among students and others living penniless lives similar to those of its heroes) about its brilliant script, stunning cinematography and extraordinary ensemble acting, it gradually became revered to the point of obsession. In turn, that obsession translated over time into a realization that it ranks not only among the finest cult movies but among the finest movies full-stop.

Now, more than thirty years after it first appeared, it is routinely regarded as being among the finest British movies ever made (right up there with the likes of The Third Man and David Lean’s classics) and its memorable, indeed infinitely quotable, screenplay is justifiably seen as one of the finest ever written. In a piece for The Script Lab on the greatest screenplays ever written, I argued that only Casablanca trumps it as the very best movie script. However, what is less well known, and certainly less celebrated, is Bruce Robinson’s own “back story” and its influence on Withnail and I.

Before becoming one of cinema’s most legendary screenwriters, Bruce Robinson himself was what is still referred to today as a “classically trained” actor, having studied at the Central School of Speech and Drama in London in the mid-1960s. It was from there that he enjoyed early, indeed almost instant, success as an actor, being cast as Benvolio by the great Italian film director, Franco Zeffirelli, in his self-consciously Sixties-influenced screen adaptation of Romeo and Juliet in 1968. Zeffirelli sought to capture at least some of the youthful spirit of the age by deliberately casting beautiful and, crucially, young actors in the film, including Leonard Whiting and Olivia Hussey as the leads. Hitherto, productions of the play on stage had generally cast actors who were many years older than the titular characters were supposed to be, but Zeffirelli was determined to use young actors to portray the ultimate tale of young love doomed by old prejudices.

This simple but extraordinarily effective casting decision was one of the major reasons for the film’s enormous commercial success, as it became, at the time, the biggest box-office success of any screen adaptation of a Shakespeare play, and Whiting and Hussey briefly became poster-boy and poster-girl for the sexual revolution sweeping the Western world. However, as befits one of Shakespeare’s greatest tragedies, there was a dark, even unseemly side to the movie, one that was instrumental in Bruce Robinson’s development both as an actor and ultimately as a writer-director.

Robinson has always claimed, in numerous interviews, that during the filming of Romeo and Juliet Zeffirelli was attracted to him and at times actively expressed his romantic or sexual interest in him. Like so many of the other young actors in the film, the young Robinson was a genuinely beautiful young man, almost a modern-day equivalent of the exquisite and delicate young men and women immortalized in so many Renaissance paintings. However, Robinson was avowedly heterosexual and Zeffirelli was not only much older (he was 45 when he filmed Romeo and Juliet) but, as the director of the film, in a position of power far greater than that of an actor making his first movie. For Robinson, it was as if the play’s overarching theme – of tender, impressionable youth being threatened and ultimately overwhelmed by the forces of age and entrenched financial power – was being brought menacingly to life.

After the success of Romeo and Juliet, Robinson continued to act for several years, including in such notable films as Ken Russell’s The Music Lovers (1970) and Francois Truffaut’s The Story of Adele H. (1975). However, as his own youthful bloom and good looks faded, he found it increasingly difficult to find work as an actor and eventually slid into the sybaritic, even alcoholic lifestyle that he would capture forever in Withnail. It was only when he hit the proverbial “rock bottom” that he turned to writing, soon replicating his initial rapid rise as an actor by being Oscar-nominated in 1984 for his superb screenplay for The Killing Fields, adapting Sidney Schanberg’s book, The Death and Life of Dith Pran, about his experiences in Cambodia during the pathological dictatorship of Pol Pot. On the back of that success, Robinson was able to gain funding from the rising British company Handmade Films (whose financiers included ex-Beatle George Harrison) to bring to the big screen his own unique vision of the end of the Sixties, Withnail and I, which included his depiction of a young, impoverished man being pursued by an older sexual predator, who was both sensitive and ruthless.

The ghost of Zeffirelli and his film version of Romeo and Juliet haunts Withnail and I. It is there at the outset when the furiously jealous Withnail reads about a young actor who has secured a “plum role for top Italian director”. As Withnail rages, “Course he does. Probably on a tenner a day. And I know what for. Two pound ten a tit and a fiver for his arse…” Of course, the “boy” in question is Bruce Robinson himself, in a direct autobiographical reference to his own experience on the set of Romeo and Juliet. But that is just the beginning, as the whole plot of Withnail and I is based on this conflation of youthful sexual appeal and commercial exchange. Withnail persuades his wealthy Uncle Monty to lend him his cottage in the country in return for a vague suggestion that the “I” character (called “Marwood” in the screenplay, though he is never referred to by name in the film) will repay him with sexual favours, a plan, of course, that “I” is blissfully unaware of.

Richard Griffiths’ Uncle Monty may be twice the size and girth of the slimmer and taller Zeffirelli but he was nevertheless modelled on him. Like Zeffirelli, he is much older and wealthier than his younger protégés, and he is also remarkably cultured, blithely quoting Latin and lamenting the decline of contemporary life. However, as he ultimately shows, he is equally capable of using his power (both physical and financial) to get what he wants. When he finally forces his way into “I”’s bedroom late at night, made up like a drag queen, he first tries to woo “I”, but when that fails he declares: “I mean to have you…even if it must be burglary.”

Now, it must be stressed that Robinson has never alleged that Zeffirelli ever pursued him in such a direct manner. Nevertheless, the idea of an older man pursuing a younger man for his own ends (and against the young man’s own wishes) was inspired by Robinson’s experience on Romeo and Juliet, and it is also telling that Withnail and I is set not in the 1970s, when Robinson’s own acting career hit the skids, but in the late 1960s, when he was actually a youthful success. The period setting is vital, because at that time, of course, homosexuality had only just been legalised in Britain and it effectively remained illegal in Italy until much later. It is in that historical context that both the real-life exploits of Zeffirelli and the fictional predation of Uncle Monty must be seen. Both were older men who obviously struggled with their own sexuality (Zeffirelli himself only came out as openly gay very late in life) and if at times they resorted to an over-zealous pursuit of younger men, then it must be remembered that during their own youth any latent homosexual instincts would have had to be suppressed for fear of imprisonment. As “I” finally says of Uncle Monty, having read the note he leaves in the cottage after fleeing during the night, “Poor old bastard”. Withnail scoffs, but that lament could have applied to an entire generation of middle-aged and older homosexual men who could not easily, or even legally, join in the sexual revolution of the Sixties.

What is perhaps most alchemical about Withnail and I is that Robinson could easily have made a salacious, “tell-all” memoir of his experiences of filming Romeo and Juliet, a big-budget movie that ultimately became a huge box-office hit. Instead, almost adapting Keats’s famous idea of “negative capability” – “that is, when man is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason” – he wrote a film about two losers (one a permanent failure, the other only temporarily) who seemingly cannot get even a part in a “cheroot” ad to save their life. And then he introduced the biggest loser of all, Uncle Monty, who, like so many of the greatest characters in literature and storytelling from Macbeth to Lolita, is a sensitive monster: a man who is outwardly charming and considerate but inwardly consumed by demons. That Robinson ultimately has both Uncle Monty’s intended victim, “I”, and the audience feel enormous sympathy for this puzzling, troubled soul is perhaps the greatest of his many achievements in writing and directing Withnail and I.