By Kevin Nelson · April 14, 2021

There are writers who have a seed of an idea, plant it, and let it grow. The story unfolds naturally. Others sit down and subconsciously spill out their souls as if they’re laying down a piano solo or abstract painting. Their creations burst out of them. Then, there are the tinkerers. The engineers and mechanics who can happily get lost for hours in analytics, studying the ways great stories are told.

Every writer is different, so your approach may vary. Whatever your process, it never hurts to take a deeper look at the screenplays that move you. No matter your career experience or intellectual prowess, it’s imperative to continue learning along your screenwriting journey.

Whether we’re conscious of it or not, the world is built in sequences, patterns, and structures. From the golden ratio down to our DNA. One of the ways that humans have come to a better understanding of the world around us is through reverse engineering these processes.

The goal of reverse engineering is to scientifically research a design, product, or system by identifying components and their interrelationships. It’s an analytical process of deconstructing individual components so that one can recreate or improve their own product.

With this in mind, screenwriter C. Robert Cargill states that, “Writing isn’t a mystical art; it’s a mechanical one.”

Imagine that it’s time to move to your dream home. When you moved into your tiny apartment ten years ago, you thought it’d be smart to buy some cheap Scandinavian furniture. You were provided the parts, the hardware, and the instructions. Assembly and tools were required. Miraculously, it came together and held up. Years later, the instructions are long gone. Great. You have to disassemble it piece by piece and either make a mental note of the steps or write them down in order to put them back together.

You can do the same thing with the latest script that moved you to tears. You might not have the instructions, but you have the tools to ensure that you can figure out how the screenwriter(s) achieved her/his/their genius.

One way to do that is to find a screenplay that is similar to your current work-in-progress in terms of form, theme, tone, and genre.

First, determine whether you’re writing a feature or for television. If you’re writing a spec television script, or even a sitcom — then reverse engineering an entire pilot can be beneficial in improving your own work. Specs are samples that demonstrate your ability to adapt to different writing styles/structures. Although specs are less in demand with fellowships and writing programs in recent years, it’s still wise to have a few strong samples in your portfolio.

Most instruction manuals have a step by-step process that starts with a hardware and part list. To apply this to screenwriting, this will be your A, B, C story and character arcs, page counts, or any other method that allows you to keep track of the parts and hardware.

To begin assembling, you’d then work on building the units. These units connect to form the whole. To create your own set of instructions, simply work in reverse.

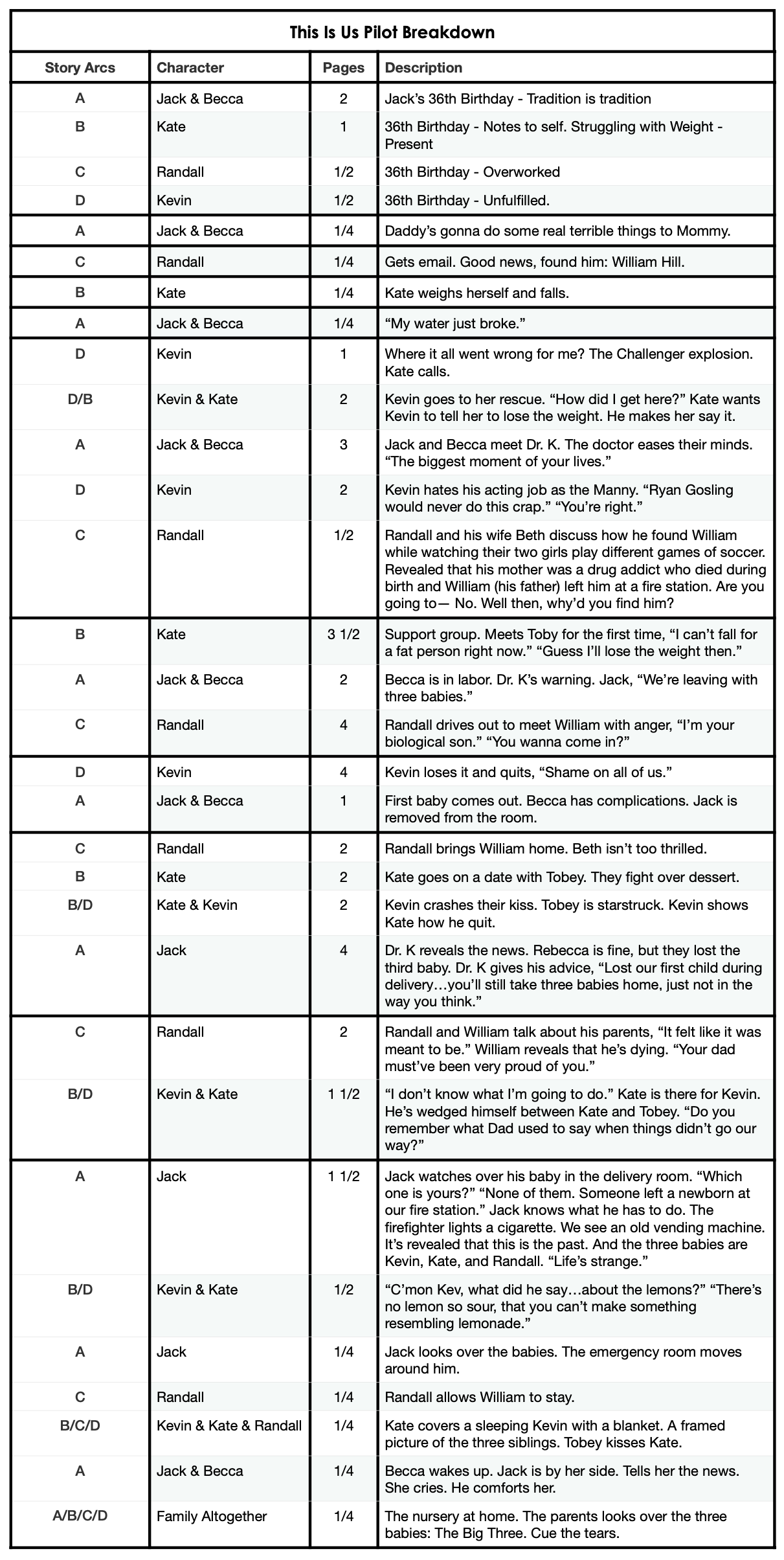

If you look at the breakdown of the This Is Us Pilot, you can get a better understanding of how Dan Fogelman weaved together multiple storylines to reach the final climactic moment.

Download the 'This is Us' pilot script here!

Download the 'This is Us' pilot script here!

Start off with the whole screenplay or show buffering before you. Break it down scene by scene, using a single sentence to describe the action as if you were creating an outline for your own pilot. I assigned the A, B, C, D labels based on the order of the characters’ appearances. You can use color-coded notecards, spread sheets, notebooks — whatever you feel comfortable with.

I often look at the final edit of the produced show as well as the script, because the editing room is the final place where the story comes together — and the final product is often better crafted than the script because more minds (director/producers/editors) have joined the think tank. You can also compare the two if you have enough time and energy. Alas, not all shooting scripts are available online. That shouldn’t prevent you from getting the information you need. This chart reflects the final aired version.

The A story line of Jack and Rebecca serves as the main narrative and anchor for which the other three stories revolve. It isn’t revealed until the closing montage that Jack and Rebecca’s storyline is set in the past, and reveals how the family was formed.

This big reveal is amplified by the lingering mystery as to how Randall fits into the picture. There’s a heartfelt call back to what Dr. K tells Jack about lemonade as it all comes together in the final sequence. You can see how all of the questions build up to the final answer. The final sequence mirrors the opening sequence in rhythm and delivery. This structure is repeated in different ways throughout the series.

Now that we have a condensed version and know how the show is structured, we can find narrative connections, rhythms, fill in the blanks, rearrange sequences and character transitions, and have a general roadmap so that we don’t get lost in recreating our own spec scripts.

Remember, just because you map out the outline/structure of a produced script, the hard work of finding captivating ways to make that well trodden space fresh and unique still lies within you.

Limited series are a lot like features in that they tell a single story with a finite end, often using similar story telling techniques — except their narratives are stretched out over multiple episodes. Like feature studies, deconstructing The Queen’s Gambit can be a cumbersome, yet rewarding pursuit.

For features and limited series — instead try focusing on specific scenes and sequences that achieve what you wish to replicate in your own work. Say, if you want to pull off the ultimate heist scene — then dive into Mission Impossible and find out how they did it so flawlessly.

In the spirit of scene work, let’s dive into the much contested subject of jump scares. A jump scare is a horror technique typically used after a short period of suspense that typically manifest in the form of a sudden noise or appearance. There are some writers who feel as though jump scares are examples of lazy writing, or that they’re easy to pull off.

The Conjuring proves that ain’t the case. Let’s see how the Hayes Brothers and James Wan developed their infamous hide & clap jump scare over the course of the script’s first act.

The Conjuring’s first act has two primary plot lines:

A: The Warrens

B: The Perron Family.

Once we have a condensed version of events, we can seek out the instances where the hide & clap game is played. Within the Perron Family’s plot line, there are two initial plot points (highlighted in bold) where the hide & clap game is played, and each time important information is revealed.

Each plot point ups the ante a bit, compounding by adding layers of mystery, leading the characters and viewers closer to the evasive truth behind the danger lurking within their malicious house. Let’s take a look:

Hide & Clap game is first played between the older sisters. It helps establish the layout of the house and leads to the discovery of the sealed up basement at the heart of the story.

The game is played between mother and daughter, making the mother further question whether there is a third player at play — despite only two people being home.

Game is played between the mother and demonic spirit — the claps leading her into a trap.

The first two instances not only reveal important information behind the house’s mystery, but they also help set up and strengthen the big pay off at the end of act one. Now that we’ve mapped out how the writers got there, let’s take a closer look at the scene.

Notice how each action leads the audience and character deeper into the darkness. To the reader or viewer, it seems like she’s being led on a wild goose chase. Yet, the desired final destination (the basement) has already been determined/established, and she’s in fact being led toward it. It’s like a siren song through a house of horrors that Carolyn feels the need to investigate.

In Action Numbers 11 & 12, we see that Carolyn’s actions reflect the original backstory of a possessed person being locked in the basement. Every beat compounds the level of tension like the tightening of a guitar string — until it’s finally so wound up that the final clap breaks it with a single strum.

This goes to show you that jump scares aren’t cheap or easy — they’re an art. The hide & clap jump scare was able to go down as one of the scariest jump scares in film history because it was developed over the course of the first act, and was punctuated by a complex and terrifying third scene. Each beat of that final scene invokes different levels of suspense, tension, and dread not easily achieved.

By studying the work of the greats before us, we can find ways to transcend them. By reverse engineering your favorite scenes and screenplays, you will inevitably come to a better understanding of your own process and proficiency. Study, hard work, and practice will only help to sharpen and improve your skills.

Technicalities and analytics aside, stories need room to grow. Characters need to be free to make their own decisions. Having a solid outline and framework doesn’t mean you can’t adapt and evolve it as the story unfolds. Nothing is set in stone. Never forfeit creativity and ingenuity for conventional wisdom.

Although there are certainly otherworldly factors behind your gifts, it’s how you wield them that matters. You’re the fuel that propels the engine with your own unique voice. These exercises shouldn’t act as a crutch. They’re a jumping board. Practice and hone your craft with childlike enthusiasm. Prepare now to present your best work to the world.

Enthrall them with your genius.