By Martin Keady · March 29, 2023

The great André Bazin, co-founder of Cahiers du Cinema, the spiritual godfather of the French nouvelle vague (new wave), and probably the most important film critic and theorist ever, argued in his book Qu’est-ce que le cinéma? (What is cinema?) that film, like flight, has always existed — at least in the mind of humanity. However, just like flight, it took the technological developments of the 19th century to turn that age-old dream, which had extended from the first shadows on the first cave walls to Shakespeare’s Muse of Fire to the earliest photography, into a reality. Let’s discover some of the first movies ever made.

Read More: What Is The Longest Movie Ever Made?

“Wethink,” or the idea of collective human creativity (rather than mere uncreative “Groupthink”), is not, contrary to much contemporary belief, an invention of the internet. However, the internet has undoubtedly facilitated it in a way that was not possible before. The idea that different people in different countries and different cultures could contribute to a succession of imaginative and technological breakthroughs really developed in the 19th century, when technological advancement and the earliest global communication allowed inventors in different continents to make similar leaps almost simultaneously. It was true of so many great 19th-century inventions, from rail to electricity, and it was true of cinema, too.

That is why it is not easy or straightforward to say definitively, “What is the first movie ever made?” The better question might be, “What is the earliest movie that still survives?” because it is possible that earlier cinematic breakthroughs were made but that the films in question just did not survive, especially given the volatile nature of early film stock.

Indeed, it is even possible to go further and say, “Well, it depends on what you mean by a movie,” because there were so many precursors. Even primitive forms of cinema before the term “movie” (as we understand it today) were fully and widely understood that the word itself can be vague and ambiguous.

The relatively new field of media archaeology attempts to answer questions such as these, not least by examining the exact origins of cinema. As Bazin rightly identified, the concept of capturing motion by some medium has existed since the earliest humans and evolved in early visual media such as shadow-play (especially in early China) and, in particular, the camera obscura.

However, it was only in the 19th century, with the mass industrialization and urbanization of the Western world, that these precursors of cinema or primitive forms of it really developed and, crucially, became more widely available and eventually popular. They included magic lanterns and the zoetrope, an optical device consisting of a cylinder with images inside which, when viewed from the outside through slits, gave a convincing impression of motion.

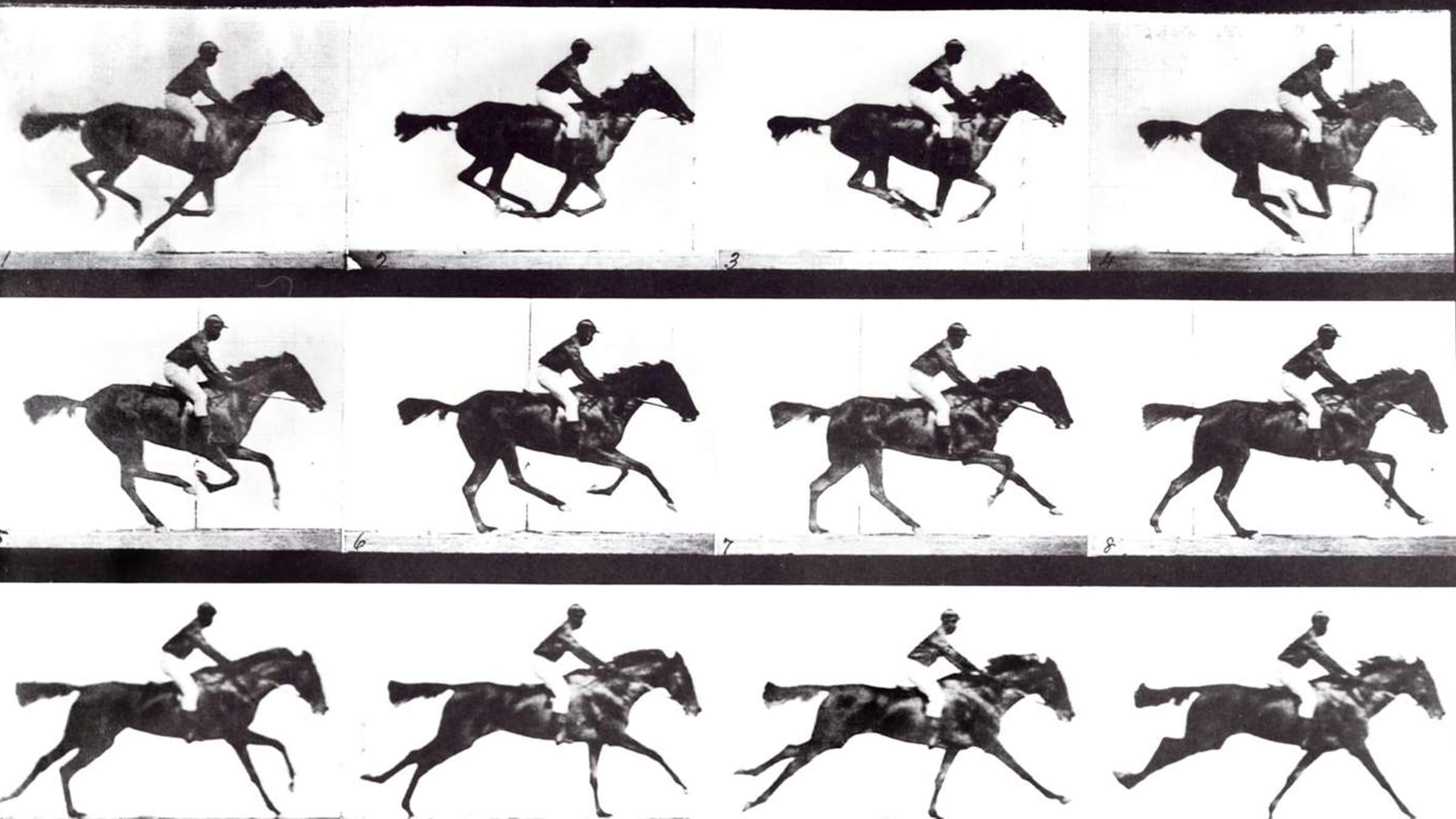

Thus, it is possible to argue (as many film historians do) that the first ever “movie” was Eadweard Muybridge’s The Horse In Motion in 1878, a sequence of a dozen photographs of a horse which, when viewed together, conveyed the sense of the horse literally being in motion.

It was the earliest example of chronophotography, which (as the name suggests) was a kind of hybrid of photography and motion photography. At the time, such images were mainly used for educational purposes rather than any kind of entertainment (let alone any artistic purpose). It is fascinating to consider that if this is the first movie ever made, then it was not really regarded as such at the time.

Indeed, the main source of the contemporary fascination with Muybridge’s The Horse In Motion was that it proved conclusively that at certain points during a gallop, all four of a horse’s legs left the ground, which had hitherto been thought impossible because it was assumed that the enormous weight of a horse meant that it always had to have at least one of its hooves on the ground. Consequently, The Horse In Motion was regarded as a breakthrough in hippology (the study of horses). The idea that it was a cinematic landmark only came later.

Another contender for the title of “The First Movie Ever Made,” or at least “The First Movie Scene Ever Filmed,” is Louis Le Prince’s Roundhay Garden Scene, which came ten years after Muybridge’s The Horse In Motion. The title (which was not Le Prince’s invention but how his footage is commonly known) says it all because this film is literally just one scene that lasts for a little more than two seconds.

Le Prince was a French inventor and industrialist who had moved to Leeds, in the north of England, in 1866, ostensibly to work for a company that made brass valves but in reality to nurture his burgeoning interest in motion photography. Roundhay Garden Scene, dating from over 20 years later, was short in running time. However, although it only depicts one scene, it is a significant scene.

In its extremely short running time, Roundhay Garden Scene simply shows Le Prince’s son, Adolphe, and three other adults (two women and another man) leaving a country house and setting off on a walk. And that’s it before the scene ends, and the film stops and almost starts to distort. However, there are two things that are particularly interesting about this footage.

The first is Adolphe’s very first step, in which the movement of his limbs (his arms in particular) seems enhanced or exaggerated, almost as if he were highlighting it or even “hamming it up” (consciously or unconsciously) for the camera. If it is the very first step ever taken on film, then it is hugely symbolically important because it prefigures the heightened, even exaggerated movement captured in so much early cinema, long before human beings became more comfortable with the idea of being filmed and realized that there is no need to exaggerate movement for it to be filmed successfully.

Louis Le Prince

The second is that Roundhay Garden Scene shows cinema itself, and not just one man, setting out on what would become its epic journey throughout the next hundred years. During this time, it would become (and then eventually cease to be) the greatest storytelling medium and arguably the most important artistic medium full-stop in human history. Indeed, it is perhaps because it captures human beings in motion, rather than animals (as in Muybridge’s The Horse In Motion from a decade earlier), that Roundhay Garden Scene is often described as “The First Movie Ever Made.”

However, it is possible to argue that Muybridge’s The Horse In Motion and Louis Le Prince’s Roundhay Park Scene are not so much the first films ever made but the first fragments of films that still survive. It’s possible to argue that they aren’t films in the modern sense, where stories are conveyed through moving images. At best, they could be considered documentaries or proto-documentaries that simply captured the world, an individual horse, or a small group of humans as they appeared.

Consequently, it is also possible to argue that the first real movies – stories told through motion pictures – only came in the final decade of the 19th century, with the breakthroughs in France (Le Prince’s native country) in the 1890s. And they were largely made by three men, two of whom were brothers.

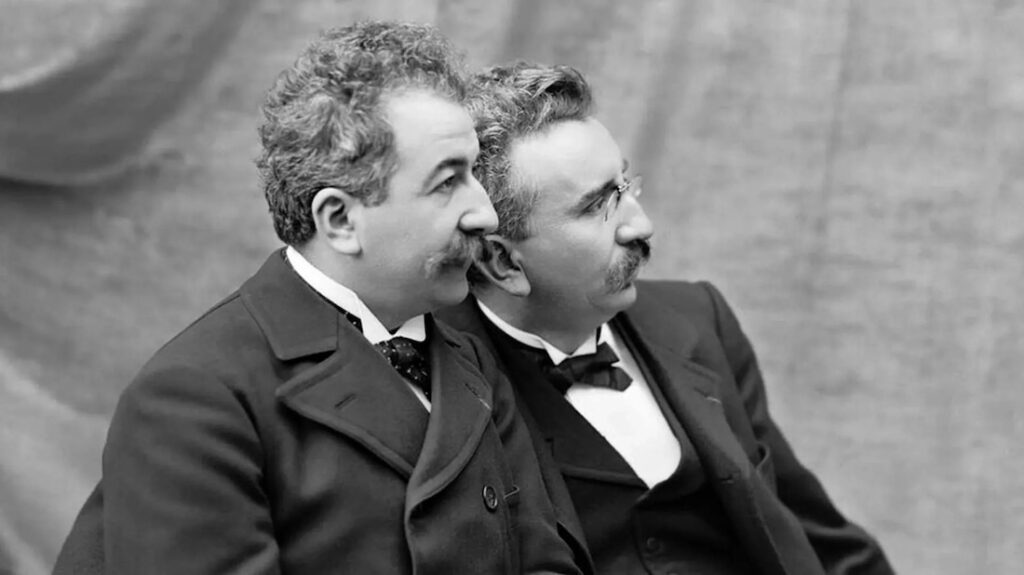

The Lumière Brothers

The Lumière brothers, Auguste and Louis, were originally manufacturers of photographic equipment, but like so many others at the end of the 19th century, they became obsessed with capturing moving pictures and not just still images. Eventually, they succeeded with their Cinématographe motion picture camera (from which the term “cinematography” derives) and used it to make a series of short films at the end of the 19th century and the start of the 20th.

Initially, the Lumières, like so many early filmmakers, only showed their work to fellow enthusiasts, but eventually, they hit upon the idea of exhibiting them to the public, who would pay for the privilege. Thus, the first-ever public screening of a film was in Paris in 1895. However, it was not of one single film but of 10 different short films, each one no more than a minute long, the most famous of which was the first, the La Sortie de l’usine Lumière à Lyon (Exit from the Lumière factory in Lyon).

In a sign of the increasing popularisation or even democratization of filmmaking itself and of what was being filmed, whereas Roundhay Garden Scene had captured just a couple of seconds of relatively wealthy people setting off for a walk around their grounds, the Lumières filmed, for nearly a minute, ordinary working men (some of their own employees) simply leaving their place of work at the end of a long day.

Nevertheless, the most famous film the Lumières ever made was L’Arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat (The Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat Station), which was first shown in public just a month later in January 1896. It did exactly what it said on the (film) can, showing a steam train arriving at a station amid great billowing clouds of smoke and water. However, what is most interesting about this film is the audience’s reaction to it, or more precisely, the possible myth that has grown up around that audience’s reaction.

Read More: The Greatest Directorial Debuts of All Time

It was claimed that so many of the original audience was so stunned by seeing their first-ever film that they genuinely believed that the train was about to crash through the screen and hit them. However, film historians have disputed this version of events and instead claimed that it was mere publicity on the part of the Lumières to generate interest in their new invention. If so, it worked, beginning the process of cinematic mythologizing or publicity generation, which ever since has taken in everyone from Orson Welles (who claimed that his radio adaptation of H. G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds was mistaken by some listeners for an actual invasion) to The Blair Witch Project (which was originally said to be actual found footage of missing filmmakers).

In film, fact and mythology can be very hard, if not impossible, to distinguish between, as is perhaps appropriate for the first medium ever to capture reality (or at least moving reality). That is why it is so hard, and perhaps always will be, to say definitively, “What is the first movie ever made?”

The early development of cinema was a process that continued throughout the end of the 19th century and in different countries. Muybridge was the father of chronophotography (or proto-cinematography, as it is sometimes called); Le Prince was the father of cinematography (actual motion picture filmmaking); and the Lumières were the pioneers of commercial filmmaking and exhibition, although, ironically enough, they eventually lost interest in filmmaking and withdrew from it completely to concentrate on photography.

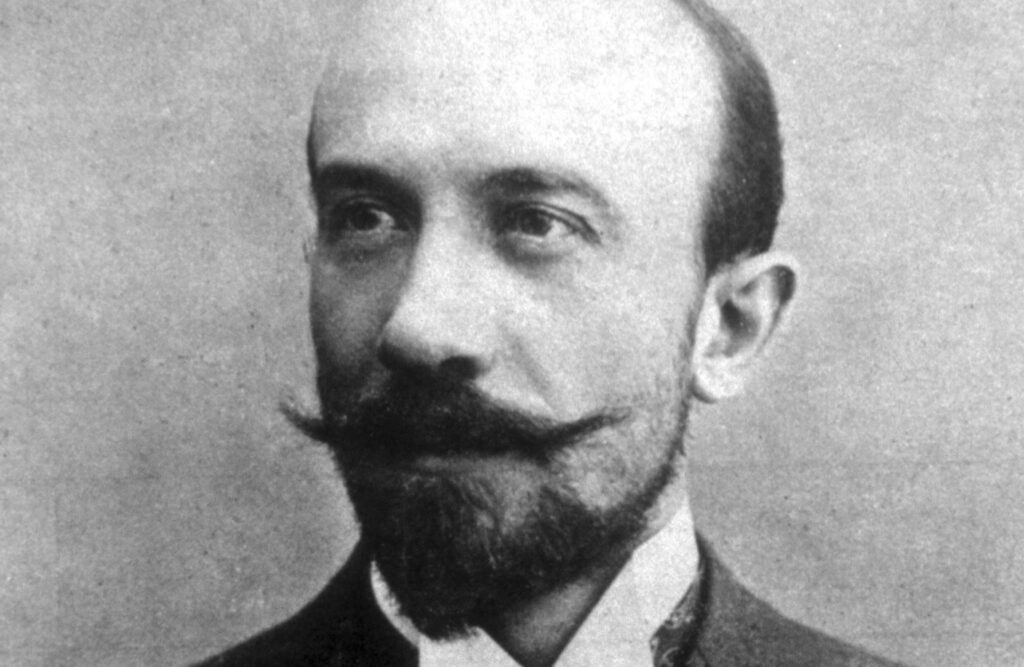

Georges Méliès

The final one of what might be called the five founding fathers of film is Georges Méliès, who can also be considered the father of narrative filmmaking or film storytelling. Like his predecessors, Méliès began with documentary or actualité filmmaking of the kind that his compatriots Le Prince and the Lumières had specialized in. However, he soon began to experiment not just with photographing reality but with shaping or even altering it, to tell stories that were not just single scenes, like Roundhay Garden Scene, or even single sequences, such as L’Arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat (The Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat Station). Instead, these were stories with recognizable beginnings, muddles, and ends, to use Philip Larkin’s famous definition of a story.

The most famous of Méliès’s films and the one that is arguably the most deserving of the title “The First Movie Ever Made,” or at least the earliest film whose influence endures to this day, was his 1902 epic, Le Voyage dans la Lune (A Trip to the Moon). It remains the original or even Ur sci-fi film; its image of the man on the moon getting a rocket in the eye remains the most enduring of all early cinema (and a foreshadowing of so much of the sci-fi cinema that would follow, as it brilliantly summarises the dangers of human interaction with other inhabitants of the universe); and, perhaps most compellingly for writers and readers of Script Lab, it had what is generally considered the first ever screenplay.

Read More: A Brief History of Screenwriting

Other film firsts would follow, most importantly The Jazz Singer (1927), the first commercially successful and widely available “sound picture”, which added audio to the cinematic mix for the first time. However, the major steps taken at the end of the 19th century were the first film firsts: the initial, often stumbling (and barely surviving) steps on the road to the cinema that we know today.

Ironically, we are now in an age when the great John Boorman (director of Point Blank, Deliverance, and Excalibur, among many others) argues that the age of film is over, such that none of the supposed “films” nominated for the 2023 Oscars (with the exception of Steven Spielberg’s The Fabelmans, which was shot on celluloid) should even be called films. And so, as cinema itself is arguably coming to an end, there may be even greater interest in its origins, and further revelations about other historical and technological triumphs may yet emerge. Consequently, it is not impossible that in 10 years’ time, the question, “What is the first movie ever made?” might just have a different answer.

Read More: A Brief History of Screenwriting