By Ken Miyamoto from ScreenCraft · October 19, 2017

You’ve heard of screenwriting competitions – but how reputable are they? How can you know which contests are legitimate, and which ones are scams? In this article, we’ll trace the long history of screenwriting competitions from the early days of Hollywood to the present day, and share bits of information about some of the most celebrated competitions.

Buckle up for a deep dive into the long and storied history of screenwriting competitions.

Writing competitions go back thousands of years. The centerpiece of the ancient Greeks’ annual Dionysia festival was a competition between playwrights at the Theatre of Dionysus dating back to before 600 BCE (and eventually actors were permitted on stage). Writers have been celebrated in festivals and competitions, and they have been remembered long after their deaths, from ancient times.

The early days of “screenwriting” go back to the birth of film in the 1890s. Back then, they were called scenarios. Films were only a couple of minutes long and scenarios provided brief explanations — written by writers and filmmakers — primarily utilized for marketing and as explanations for audiences that weren’t used to experiencing entertainment in this then revolutionary technology.

As films became more narratively complex, they went from just one “scenario” to many. One of the first examples of the modern screenplay was from George Melies’ iconic 1902 film, A Trip to the Moon. The script had thirty-some lines of basic descriptions that provided action and locations.

As cinematic narratives grew, so did the film industry. The first movie theater opened in 1905. By 1910, there were ten thousand movie theaters in the United States alone. Audiences were engrossed with cinema. And as with any budding industry, the more popular it became, the more people wanted to be involved.

Budding storytellers began to write their own scenarios. As the film industry grew, the existing studios making movies at the time were bombarded by submissions.

In 1913, Moving Picture World magazine reported that likely over twenty thousand fans had written their own movie “scenarios.”

To engage the fans and to discover talent, studios began to offer cash prizes for the best scenarios. And thus, the screenwriting competition was born.

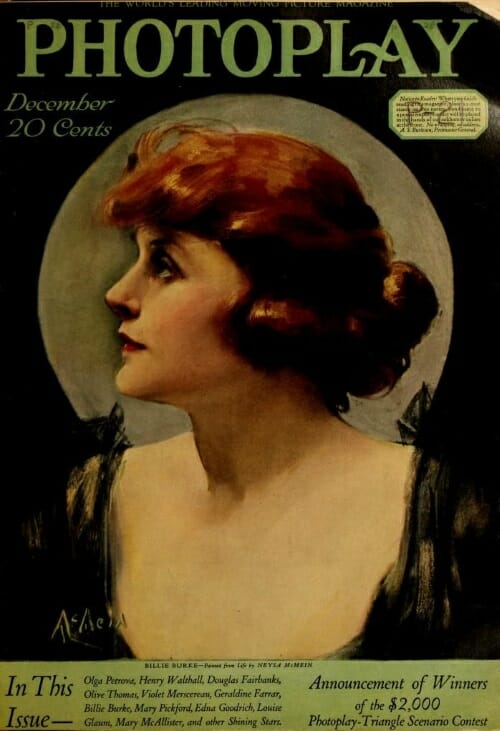

Fan magazines like Photoplay worked with studios to collect success stories and even began to publish advice articles on how to write for the cinema. Dozens of screenwriting schools and scenario advice books — like Louella Parsons’s How to Write for the Movies (1915).

James Quirk, the editor of Photoplay magazine, realized that intrigued cinematic audiences not only wanted to watch movies, but they wanted to participate in them as well. And he also observed that women trying to break into the film industry as actresses were being taken advantage of — often in the most negative of ways.

He later wrote that writing screenplays was a safe way to enter the film industry for women. It was challenging, creative, and crucial to the filmmaking process — and it offered possibilities for fame and fortune. Because of such articles, many early screenwriters of that time were women.

Between 1915 and the early 1920s, Photoplay worked hard to convince women that their futures lay in screenwriting rather than the pursuit of being a Hollywood starlet in front of the camera. Quirk himself promoted the trade as the ideal pursuit for women of all aspirations and backgrounds.

A housewife named Cordelia Ford, earned a $250 cash prize in a screenwriting contest.

Helen O’Keefe, who usually wrote after her children went to bed, paid off all of her debts after winning a cash prize from the American Film Company.

Ida Damon, at that time working as a stenographer, won what was then an astronomical figure of ten thousand dollars from a screenwriting contest awarded by the Thanhouser Film Corporation.

Elaine Sterne, winner of Vitagraph Studio’s International Scenario Contest, was later hired by Photoplay to write a monthly column entitled Writing for the Movies as a Professional.

Many of the women that began to win these early screenwriting contests would later become the literary voices behind such iconic Hollywood filmmakers as Cecil B. DeMille, Douglas Fairbanks, Rudolph Valentino, and many others.

By the late 1920s, Photoplay Magazine began to focus their attentions on the glitz and glamour of Hollywood — accompanied by creative advertising for products. The screenwriting articles began to disappear — as did the screenwriting contests.

Not much is written about screenwriting competitions in the couple of decades after the 1920s. There were certainly contests that continued on, but the majority of writing competitions seem to have shifted focus to literary fiction as the ripples of the Great Depression affected the film industry.

Despite the economic hardship faced by nearly everyone in the country in the 1930’s, many millions of Americans still packed into theaters each week. Why? Escapism from the difficult times.

Musicals became the highest grossing genre of film, and helped to entertain the masses during the Great Depression. Stars such as Judy Garland, Mickey Rooney, Shirley Temple, and Fred Astaire became models of strength, courage, optimism, charisma, vulnerability, and triumph.

Scenarios were no longer being written nor requested — long forgotten as the cinematic narrative built to feature length movies. Original screenplays were less in demand, with the studios now instead opting for more musical compositions.

The most notable screenwriting competition during this time was started by legendary movie pioneer Samuel Goldwyn, Sr.

In 1955, to celebrate his 75th birthday, he started the Samuel Goldwyn Writing Awards at UCLA to encourage young stage, film, and television writers. Notable winners included Francis Ford Coppola, Eric Roth, Pamela Gray, Allison Anders, Colin Higgins, Carroll Ballad, Scott Rosenberg, and Jonathan Kellerman.

The success history of the Samuel Goldwyn Writing Awards is impressive, with winners having later written more than 300 films, television series and made-for-TV movies — and have won a total of 27 Academy Awards with 101 nominations, 35 Golden Globe Awards with 189 nominations, and 87 Emmys with 488 nominations. Previous winners have also become popular authors who, collectively, have published over 60 books — many of which were New York Times bestsellers.

However, this wasn’t an open competition. Only regularly enrolled undergraduate or graduate students at UCLA could partake — a stipulation that continues to this day.

During the 1960s and 1970s, cinema began to change. The counter-culture movement began to bleed into the film industry. The days of actor, director, and screenwriter studio contract deals for multiple pictures began to dissipate. Auteur filmmakers were all of the rage and studios began to take more risks to answer the call of the times in a Vietnam and Post-Vietnam era of cinematic storytelling.

In 1979, Willard Rodgers — a graduate of the American Film Institute’s directors’ program — started the AFI Alumni Association Writers Workshop. At that time, Rodgers convinced the alumni board that talented starting writers could benefit from a process that begins with professional supervision of their scripts and ends with a reading by professional actors and an audience critique.

This was a shift in screenwriting contests. Screenwriters would still submit their scripts to the program, but those that advanced would now benefit not from cash prizes, but through industry access and mentorship where they would work directly with industry professionals during and after the writing process.

At the time, such a process was unheard of — especially the concept behind having the script read in an open forum by professional actors and later critiqued by industry insiders.

“There had not been one word written on staging a screenplay before a live audience,” Rodgers said. “Live readings are valuable in giving writers feedback. Sometimes, you just don’t know what the problems are until an audience tells you.”

“Seeing your writing acted out in front of an audience gives you a sense of its impact,” said Oliver Stone, who moderated one of the readings. “I think it would have helped (me) enormously if there’d been something like it when I was starting. I think I could still use it.”

Novice screenwriters often first read about the program through a regular ad placed in the Writer’s Digest.

According to an old L.A. Times article, Tom Homans was a 24-year-old college graduate counting engine parts in a Baltimore warehouse when he first saw the ad. He was an aspiring writer that had a story about a Little League baseball star. He sent in “what read like a 200-page essay” with the $50 application fee and six months later he had an agent at William Morris, an option at Lorimar, and was living in an apartment at the bottom of the hill below the Hollywood sign.

A newspaper article about Homans’ success caught the eye of J.B. Mackey in Texas. Mackey and his wife traveled to Los Angeles that day with his story about a sociopathic child and his demonic dog. Mackey didn’t even have a full script. Instead, he submitted fifty pages of hand-written notes with dialogue. Neither of them had any clue about the format of a screenplay. But they were accepted into the workshop program nonetheless.

“I look for that raw talent,” Rodgers said. “I can teach somebody the screenplay form in three hours. But it won’t help if they don’t have a story.”

Major films like Cross Roads and River’s Edge emerged from workshop readings.

The workshop itself was considered one of the best kept Hollywood secrets at the time — but not by design.

“When you add in Xeroxing and some other things, it’s a tough way to make a living,” he said.

The program costed the accepted writers money as well. According to the article, the most writers would spend to complete the workshop was $450. Rodgers estimated the actual cost for each “graduate” at $2,500.

Hollywood’s talent agencies, independent production companies, and major studios contributed in making up the deficit.

The entire workshop process took less than six months on average — primarily depending on the original condition of the screenplay and how hard and fast the screenwriter could write. Rodgers read the scripts first, then sent them out to volunteer professional writers. When the script was far enough along, it was scheduled for one of the two readings held each month.

After the script was critiqued and a final draft was written, Rodgers copied the script and sent it out to his list of 39 companies and agencies that would read every workshop script submitted to them.

If any of the submitted scripts were bought, or put into active development, the writers were obligated to return 5% of their earnings from those projects to the program.

Rodgers died in 2010 and the AFI Alumni Association Writers Workshop is now just a distant memory.

In 1985, the esteemed Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences — those behind the annual Academy Awards —created what is still known as the most heralded screenwriting competition of them all. Gee Nicholl and Julian Blaustein were behind the development of a program that would aid new screenwriters — that program ultimately became the Don and Gee Nicholl Fellowships in Screenwriting, now known as the Academy Nicholl Fellowships.

The competition was initially limited to California college students. During the first year in 1986, the 99 budding screenwriters that entered could submit a screenplay, a teleplay, a TV series episode, fiction, or a stageplay. The first Nicholl fellowships were awarded to Allison Anders, Dennis Clontz, and Jeff Eugenides.

In 1987, the Academy Nicholl Fellowships expanded eligibility to include college students in nine states and to residents of Texas. Two years later, eligibility was expanded again to include any and all United States residents who had not sold or optioned a screenplay or teleplay.

In 1989, Fellowship winner Radha Bharadwaj became the first fellow to have her Nicholl entry script released as a feature film —1991’s Closet Land.

Very few contests beyond the aforementioned programs were running in the 1980s — at least at the national level. This was primarily due to the work that went into conducting such a contest. At the time, there was no internet. Submissions had to be mailed and copies had to be made. There was also no email correspondence, so mailings had to be sent out for marketing, submissions, and notifications.

It wasn’t until the 1990s that the screenwriting contest began to see the surge that the secondary industry hadn’t seen since the early 1900s.

By the time the 1980s ended, the industry was thrown into chaos as a result of the 1988 WGA Strike. By the time the strike ended there was a sudden high demand for content, resulting in a plethora of original screenplays — spec scripts — that were sold for millions.

Alan Gasmer, a William Morris agent during that time, started the trend of putting such scripts on the market for only a limited amount of time, with the auction block opening on Monday and closing at the end of that Friday. The result led to a competitive streak among the studios, leading to a ridiculous amount of big sales that we haven’t seen since. In 1990 alone, 14 scripts were sold for $1 million or more.

Spec scripts like Milk Money ($1 million), Radio Flyer ($1.25 million), Medicine Man ($3 million), Basic Instinct ($3 million), The Long Kiss Goodnight ($4 million), and many more were purchased and eventually produced — to varying degrees of success. And even more were bought six to seven figures, only to never see the light of day.

This boom sent waves across the country and world. Everyone wanted in.

Los Angeles was no longer a destination for an immeasurable amount of hopeful actors — hopeful screenwriters began to take over as the ultimate Hollywood cliche.

While the Nicholl Fellowship, Samuel Goldwyn Awards, and AFI Alumni Association Writers Workshop were still going strong, other contests began to slowly appear.

The Disney/ABC Writing Program was created in 1990 in partnership with the Writers Guild of America and quickly became one of the most widely recognized and coveted industry writing programs — even to this day.

The one-year program is the only program of its kind designed under terms approved by the WGA and has launched the careers of many successful writers. It offers writers the chance to receive a weekly writers salary for a year while working for and learning from the television industry’s best. It also provides access to executives, producers, and literary representatives through various meetings and events designed to facilitate relationships that can prove invaluable in developing a television writing career.

The Chesterfield Writer’s Film Project followed in those footsteps, offering both television and feature writers a similar experience with a year long fellowship complete with access to and direction by industry insiders. It originated at Steven Spielberg’s Amblin Entertainment and was then sponsored by Paramount Pictures and overseen at the studio by Paramount Motion Picture Group Vice Chairman John Goldwyn and Senior Vice President of Production Dede Gardner.

WFP alumni have written scripts for nearly every studio and major independent including Paramount Pictures, Disney, Universal Pictures, Warner Brothers, DreamWorks, Sony Pictures, MGM, Imagine Entertainment and American Zoetrope and were represented by the Creative Artists Agency, International Creative Management, the William Morris Agency, and the United Talent Agency, among others.

There was even a contest that was created by an international writers group based two thousand miles away from Los Angeles — in Madison, Wisconsin. The Wisconsin Screenwriters Forum accepted membership from all states and all countries, eventually growing to be three hundred strong in membership.

Their screenwriting contest — and the organization itself — were known well enough in the industry to earn a mention in Dave Trottier’s The Screenwriters Bible.

One of the more immersive contests came from Robert Redford’s Sundance Institute, in conjunction with the Sundance Film Festival which is clearly the premiere event of the year for filmmakers worldwide.

The celebrated Sundance Screenwriters Lab proved to be an amazing launching pad into both indie cinema and Hollywood. This competition allowed screenwriters to network and meet some industry professionals, but also served as perhaps the best possible education they could receive in screenwriting and storytelling through film overall.

The Screenwriters Lab is a five-day writer’s workshop that gives independent screenwriters the opportunity to work intensively on their feature film scripts with the support of established writers in an environment that encourages innovation and creative risk-taking. Through one-on-one story sessions with Creative Advisors, Fellows engage in an artistically rigorous process that offers them indispensable lessons in craft, as well as the means to do the deep exploration needed to fully realize their material.

They only accept 12 projects each year. Some of Hollywood’s greatest talents have gone through the various Sundance Labs, including famous auteurs like Quentin Tarantino and Paul Thomas Anderson.

Coming in second to the stature of the Academy Nicholl Fellowship that was created in the middle of the 1980s, the Austin Film Festival came onto the screenwriting contest scene in the middle of the next decade — 1994 to be exact. Independent cinema was booming and the AFF reached out to screenwriters to help hone their skills. AFF was originally called the Heart of Film Screenwriters Conference and functioned solely to launch the careers of screenwriters that were historically underrepresented within the film industry.

Started in 1994 by Barbara Morgan and Marsha Milam, the AFF’s competition was roughly one of a handful of screenplay competitions in operation.

When Barbara and Marsha started the Austin Screenwriters Conference, they gave advancing writers an opportunity to attend panels and network with industry panelists. Producers Barry Josephson and David Valdez were asked to attend and judge, which later resulted in them optioning the winning script Excess Baggage by Max Adams. The script would eventually be produced into a feature film starring Alicia Silverstone and Benicio del Toro.

This ultimately put the the Austin Film Festival on the map for aspiring screenwriters and their number of entries continued to grow each subsequent year.

“Since our inception, we really pride ourselves in maintaining our mission for championing writers. This year, we received over 9,400 submissions in our various categories,” AFF Screenplay Competition Director Matt Dy commented.

AFF led the charge in offering screenwriters professional feedback as well through contest. Reader Comments — a brief paragraph of one reader’s “overall” notes — are provided to all entrants. Second Rounders and above receive further Reader Comments based on specific criteria. This then unique feature offered writers the chance to learn from industry readers, something that later contests would develop even further.

They also were one of the first contests to send finalist scripts to major production companies — a feature that was implemented at a time when spec screenplays were in high demand.

But despite the boom in spec script sales and the ripples of wide interest that followed, screenwriting contests were still relatively few and far between.

Hollywood screenwriter Sean Hood (Conan the Barbarian, The Legend of Hercules, and Halloween: Resurrection) commented, “I went to film school between ’95 and ’98 and at that time, everyone talked about getting a short film into festivals, especially Sundance, but no one talked about screenplay contests.”

But as technology grew and began to catch up with the industry, things changed.

Moviebytes creator Fred Mensch commented on the impact that the internet made, “When MovieBytes went online in 1997, there were only about 35 or 40 contests worldwide, and most of them were pretty obscure. Almost immediately, though, we started getting 2 or 3 new submissions every week, and our database just took off. We were soon tracking hundreds of contests of all shapes and sizes.”

The screenwriting contest industry was reborn, showcasing a widespread draw that hadn’t been seen since the early days of cinema.

The internet made all of the difference. Contests could now be found with ease and were no longer regional. They were international. Screenwriters now had a platform to find places to submit their screenplays easily online, from anywhere in the world.

Places like Moviebytes became a clearinghouse for screenwriting contest info, both good and bad. Screenwriters could review contests and communicate to others whether or not they were worth the submission.

The technology grew as the 20th century made its into the 21st.

“The big shift in my awareness of screenplay contests came about when Withoutabox changed the way filmmakers submitted to festivals. It was suddenly clear that all these screenplay contests existed, and more and more sprung up with each passing year,” Sean Hood remembered.

Withoutabox was website founded in January 2000 by David Straus, Joe Neulight and Charles Neulight and allowed independent filmmakers to self-distribute their films. The first product launched was the International Film Festival Submission system. It offered filmmakers a platform to submit their films to over 850 film festivals worldwide. This opened up the doors for screenwriting contests to utilize the platform as well.

Contests could now request submissions via the web and manage incoming submissions electronically, instead of the traditional route of sending hard copies. Companies could market their contests, competitions, and festivals to over 400,000 active filmmakers and screenwriters already on the platform. They could also accept submission fees from them electronically, and automatically notify filmmakers for acceptance into their event.

It offered a revolutionary approach to writing contests and would give birth to hundreds of additional screenwriting contests.

Scriptapalooza, BlueCat, Final Draft’s Big Break, PAGE International Screenwriting Awards, Script Pipeline, Slamdance, and many others were born as the first decade of the 2000s brought forth the internet, social media, and overall technological advances that allowed screenwriters to find contests and submit with ease. BlueCat most-notably was founded by Gordy Hoffman, brother to the late actor Philip Seymour Hoffman.

Cash prizes got bigger and more and more contests were offering access to the industry, as well as in-depth feedback from professional readers. Studios began to enter into the mix, with Universal, Warner Brothers, Fox, and Disney offering their own in search of undiscovered talent.

Nearly every major film festival began to widely promote their own screenwriting competitions as well.

Between the years of 2000 and 2008, the rate of screenwriting competitions began to increase, creating an oversatuated industry.

If you visit Moviebytes.com today, you’ll find 553 records of contests to choose from.

The promise of industry access became a game of which contests were true to their word, as far as what access they could offer.

And then, in late 2007 and early 2008, the film industry underwent a drastic change after a new WGA strike was accompanied by one of the worst economic disasters since the Great Depression. It became more difficult for screenwriters to break through by going directly to production companies, studios, management companies, and agencies. If no major intellectual property (“IP”) was attached to any pitched project, it was next to impossible to get a meeting.

But as the strike ended and the economy began to recover, the second decade of the 21st century begin to showcase a new resurgence of the screenwriting contest and its impact on the industry.

Tracking Board’s Launch Pad leveraged its industry community and utilized it as a draw for screenwriters.

Their Launch Pad competitions — pilots, features, and manuscripts — have helped dozens of writers elevate their professional careers, sell their scripts and even get staffed on television shows.

ScreenCraft co-founders Cameron Cubbison and John Rhodes made the jump from Hollywood development and acquisitions jobs to launch a screenplay development firm specializing in screenwriting competitions by genre, aimed at discovering talented screenwriters and connecting them with producers, agents, and managers.

ScreenCraft’s Screenwriting Competitions uniquely tailor the prize package and jury for each contest — eliminating potential genre bias — by specializing in screenplay competitions by genre. Their script coverage options and consulting packages offer some of the best and most detailed industry feedback that screenwriters can find outside of the studio system.

Organizations like Shore Scripts are notable in the way that they are committed to the production of their prize winning scripts. Not only do they offer a range of contests geared towards TV pilots, features, and shorts, Shore also commissions at least one short film with a budget of up to $15,000 each year through their annual Short Film Fund.

Newer contests are also making strides in cultural ways by focusing on finding more diverse voices in screenwriting. WeScreenplay is a company that not only run excellent feature, short, and television contest — along with coverage — but also runs a specific Diverse Voices competition that strives to provide a contest that is purely focused on promoting and encouraging diverse voices and stories.

The contest encourages stories that are told from diverse perspectives — through the author and/or characters — that are often underrepresented in Hollywood today. The contest accepts Features, TV Pilots, Web Series, and Shorts.

Perhaps the most revolutionary advancement in screenwriting contests — at least in terms of access to the film industry — came from one of Hollywood’s staple annual surveys: The Black List.

In 2005 Franklin Leonard surveyed almost 100 film industry development executives about their favorite unproduced scripts from that year, and he called it The Black List. Since then the voter pool has grown to 500 film executives, 60% of whom typically respond.

In 2012, Leonard decided to leverage the brand online, creating a script hosting service that charges members a $25-per-script monthly hosting fee plus an optional one-time $50 charge to get the material evaluated. Screenplays that receive high ratings from one of Blcklst.com’s script analysts get recommended to movie executives.

“It’s essentially a screenplay competition but it’s also more than that,” Leonard said to Wired. “We’re delivering the best scripts directly to the hundreds of people who can help get them bought and made.”

Using the Hollywood clout of Leonard’s annual survey generated a strong response from aspiring writers and the industry. Development executives, producers, managers, and agents receive regular emails from the site and can log in and peruse the database of loglines and scripts themselves.

The drawback to screenwriters is that the hosting can get quite expensive. It’s not uncommon for some writers to spend over $1,000 per year hosting their projects and getting feedback.

With that in mind, in comes another leap into the future of screenwriting competitions, talent discovery and access to industry professionals — The Script Lab is excited to announce the launch of Coverfly.

Coverfly is a free network connecting emerging screenwriters with industry professionals.

Coverfly is the industry’s largest database of screenwriting competition entries, connecting the industry’s most highly-regarded competitions into a single database for industry insiders to search and discover emerging talent. Users can sync their Nicholl and Black List accounts, as well as enter top competitions all in one place – and much more.

Scripts and scores are automatically tracked in one central dashboard, and it’s free to join!

We welcome your input! Feel free to join Coverfly and give us your thoughts. We will continue to develop and improve the platform with even more features and services.

Ken Miyamoto has worked in the film industry for nearly two decades, most notably as a studio liaison for Sony Studios and then as a script reader and story analyst for Sony Pictures. Make sure to read his growing archive of posts at ScreenCraft for more inspiration.

He has many studio meetings under his belt as a produced screenwriter, meeting with the likes of Sony, Dreamworks, Universal, Disney, Warner Brothers, as well as many production and management companies. He has had a previous development deal with Lionsgate, as well as multiple writing assignments, including the produced miniseries Blackout, starring Anne Heche, Sean Patrick Flanery, Billy Zane, James Brolin, Haylie Duff, Brian Bloom, Eric La Salle, and Bruce Boxleitner. Follow Ken on Twitter @KenMovies

For all the latest from The Script Lab, be sure to follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

If you found this article interesting, ScreenCraft has a great post on the History of Modern Screenplay Formatting.