Sign up for the

TSL Newsletter

and get $50 off Final Draft 12

By Martin Keady · May 12, 2015

For all their vast difference in appearances, Bogey is the male Marilyn – the greatest, most iconic and most enduring movie star of his sex. However, whereas Marilyn made arguably only one absolute, unquestionable classic, Some Like It Hot, Bogey made at least half a dozen, maybe more, and in the process established the template for the movie “tough guy” – but one with the most sensitive of souls.

Here are his Top 10 movies.

10. PLAY IT AGAIN, SAM

(1972, Directed by Herbert Ross, Written by Woody Allen, based on his play of the same name)

Of course, just as Bogey himself never actually said, “Play it again, Sam” (the “again” was a misquote that stuck), he doesn’t actually appear in Play It Again, Sam: it is his ghost, or memory, or even essence, as embodied by the actor Jerry Lacy (who bore a considerable facial similarity to him) that appears alongside Woody Allen in one of his finest “early funny” films. This “spirit of Bogey” manifests itself to Woody’s neurotic film critic, Allan Felix, as he watches Casablanca and dreams of emulating his idol (particularly in his no-nonsense attitude to women), while fearing that he can never do so.

It is a testament to the cinematic, indeed mythological, status of Bogey that he “haunts” this movie, just as he has arguably haunted cinema ever since his death in 1957. While there have been many male movie stars since, some of whom (notably Harrison Ford at his 1980s peak) have matched the box-office success and critical acclaim of their fabled forebears, there has never been anyone to match the simultaneously cynical but romantic allure of Bogey. As one of his greatest directors, John Huston, said at his funeral: “There will never be another like him.”

Eventually, of course, Woody’s character realises this too, and realises that he must hew his own path in life and love. Indeed, it was not just Woody’s character who realised this, but Woody himself. Play It Again, Sam, which was based on his hit Broadway play, was one of the last major films that Woody wrote but did not direct, as the studio had insisted on the hiring of an older, trusted director in the form of Herbert Ross. Despite the film’s success, Woody vowed that he would always direct his own material thereafter and with a few major exceptions, such as The Front (directed by Martin Ritt), he has done so ever since. It was as if the spirit of Bogey (utterly self-reliant and independent) had imbued even nervous, little Woody, as it has imbued all the other millions of nervous little men who have seen and loved Bogey’s films.

9. SABRINA

(1954, Directed by Billy Wilder, Written by Billy Wilder and Ernest Lehman)

Bogart was a great actor as well as a great star and could play against tough-guy type, as proven by Sabrina, in which William Holden plays the usual “Bogey character” of cynical playboy while Bogey himself plays the workaholic older brother trying to hold the family business together. He does so even as he joins Holden in falling for the charms of Audrey Hepburn’s Sabrina, the daughter of the family chauffeur who returns from a trip to Paris as a fully fledged swan, having formerly been an unnoticed ugly duckling.

Famously, Bogart found it difficult to play a quieter, more reserved character such as this, even though he is the one who ultimately wins Sabrina’s heart. He argued with Wilder throughout filming, constantly fearing that he had been miscast, and Wilder always claimed that his handling of Bogart had been one of his greatest acts of “man management” in his long career as a director. Nevertheless, the result is a completely charming film that made Hepburn a star in her own right (and not just Katharine’s famous namesake) and demonstrated the immense range of Bogart’s acting ability.

8. THE AFRICAN QUEEN

(1951, Directed by John Huston, Written by John Huston, James Agee, Peter Viertel and John Collier, based on the novel of the same name by C.S. Forester)

Of course, Bogart starred with, and won the heart of, the other Hepburn in The African Queen, John Huston’s superb WWI-set adventure movie, a film so epic in conception and scale that it later gave rise to a thinly disguised “making of” movie, Clint Eastwood’s 1990 film, White Hunter, Black Heart.

“The African Queen” is the name of the steamboat that Bogart’s wonderfully named Charlie Allnut uses to help Hepburn’s missionary to escape from the German soldiers who destroyed her mission and killed her brother. However, Hepburn, the first truly feminist female movie star, is at least as tough as Bogart and ultimately seeks revenge upon the Germans by using Bogart and his boat to launch a daring, in fact suicidal, attack on a much larger and heavily armoured German gunboat.

Like so many classic movies of the past, The African Queen almost demands a digital makeover, as so many of the scenes aboard the boat are shot against backdrops, which undoubtedly lessens their impact. However, what is absolutely unimprovable is the chemistry between Bogey and Hepburn, culminating in the marvellous ending of the film, which is one of the finest examples of the “Now get out of that” dictum of cinema, as they not only manage to sink the German gunboat but get married in the process.

Incidentally, The African Queen is one of the finest examples of a sub-genre of Bogey movies, namely the “Bogey at sea” movie. (See also To Have and Have Not and Key Largo, below.) A fanatical sailor himself (he regarded sailing as the perfect escape from the imprisoning effects of fame), he was often drawn to material about the sea. In The African Queen, the sea is his final destination as he and Hepburn head downriver towards the German gunboat, encountering obstacles ranging from waterfalls to mudflats, and the authentic depiction of life aboard a boat is entirely befitting of one of the great naval novelists, C.S. Forester, who also wrote the famous “Hornblower” series of books about Napoleonic naval warfare.

7. TO HAVE AND HAVE NOT

(1944, Directed by Howard Hawks, Written by Jules Furthman and William Faulkner, based on the novel of the same name by Ernest Hemingway)

For all that he starred with almost all of cinema’s leading ladies of the 1940s and 50s, including both Hepburn women, Bogey is always associated with just one woman, Lauren Bacall, who he met on the set of To Have and Have Not, fell in love with and later married. Their on-screen double act in this film is almost the definition of “screen chemistry” and it is no surprise that it eventually caused a real-life explosion in both their lives, as Bogart left his first wife, Mayo, to be with the beautiful co-star who was nearly a quarter of a century younger than him.

Some have dismissed To Have and Have Not as “Casablanca-lite”, and certainly there are enormous similarities in plot, theme, characterisation and even music, with Hoagy Carmichael the equivalent of “Sam” in Casablanca as another mordant pianist sidekick. However, that is to dismiss a fine film in its own right, one of the finest features of which is Bogey’s relationship with his supposed crew mate, Eddie, played by Walter Brennan. Eddie is an alcoholic and Bogey’s enemies withhold booze from him to try and prise out valuable information. Nevertheless, Bogey remains loyal to his friend, a much older man, and the relationship between Brennan and Bogart is emblematic of many relationships between Bogey’s generally middle-aged characters and their much older colleagues (for example, his relationship with Walter Huston’s character in The Treasure of The Sierra Madre). Famously, Bogey himself came to fame late, having been a bit-part actor for many years, and he always seemed to identify easily with older, less successful men, as if he realised that their fate could easily have been his, too.

6. KEY LARGO

(1948, Directed by John Huston, Written by John Huston and Richard Brooks, based on the play of the same name by Maxwell Anderson)

AKA “the hurricane movie,” in which Bogey’s war veteran, Frank McCloud, is trapped inside a Florida hotel by Edward G. Robinson’s gangster, Johnny Rocco, as a tropical storm approaches. When the storm finally strikes, hostages and hostage-takers are bound together, and typically Bogey initially rebuffs all attempts to be heroic, before finally revealing his true heroism when Rocco orders him to sail him to Cuba and he has to rebel.

Key Largo is, in many ways, the classic Bogey movie, featuring a great performance by Bogey himself; great support from, among others, Bacall as the war-widow with whom he falls in love; a great villain, in the redoubtable Edward G.; and above all a great script and great direction by John Huston. For all Bogart’s own inestimable abilities as an actor, he was always astute enough to appreciate the importance of great writing and direction, and it is no coincidence that he was so often the leading man for the leading directors of his era, including Huston, Hawks and Wilder. Obviously, they all saw in him the absolute embodiment of, for want of a better term, “the spirit of the age:” a man who knew his own absolute unimportance in a world at war and who consequently assumed almost mythical significance as the unglamorous face of genuine, stoical heroism.

5. THE TREASURE OF THE SIERRA MADRE

(1948, Directed by John Huston, Based on the novel of the same name by B. Traven)

This is a tale of Bogey being lost on land, as opposed to being lost at sea, as he joins two other destitute “desperados” (played by Tim Curtin and Walter Huston, the director’s father) in their search for the mythical Mexican treasure.

The original tagline for The Treasure of the Sierra Madre was, “They sold their souls for…” the titular treasure. As so often with those classic taglines, it was simple but effective, as the film unflinchingly depicts the corrupting effect of money, and by implication capitalism in general, as the treasure-hunters eventually find the gold, only to turn upon each other and anyone else trying to stake a claim to it.

What is perhaps most fascinating about The Treasure of the Sierra Madre is that Bogey is as much the villain as the hero of the film; he is the most venal of the three treasure-hunters and ultimately pays the highest price by losing his life. It must have been a considerable shock to the original audience to see Bogey, who by this time was already probably the biggest star in cinema, not only playing a thoroughly disreputable and unlikeable character but perishing because of it. As The Treasure of the Sierra Madre demonstrates, Bogey was never afraid to explore his own “dark side” on screen and was always at the service of the film and its director in a way that is almost alien to most of the movie stars who succeeded him.

Incidentally, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre was the inspiration for another great work of art, or more specifically music: Fool’s Gold, the finest moment from the Stone Roses. When Ian Brown sang, “The pack on my back is aching,” he was trying, at least in part, to channel the spirit and determination of Bogey and his fellow misguided adventurers.

4. THE BIG SLEEP

(1946, Directed by Howard Hawks, Written by William Faulkner, Leigh Brackett and Jules Furthman, Based on the novel of the same name by Raymond Chandler)

In post-war Hollywood, the stars weren’t just on the screen; they were also working away off-screen, writing and rewriting the stories that entertained and entranced the world. Bogart not only worked with great directors but with truly great writers, including Hemingway, Faulkner, Chandler and Hammett. That is almost unimaginable today, in a movie industry that seemingly draws more inspiration from videogames than from literature. Now, if great novelists write for the screen at all, they write for the small screen, not the big one, as exemplified by the work of Richard Price, George Pelecanos and Dennis Lehane on The Wire.

Nevertheless, for all the stellar literary ability involved with The Big Sleep, it is almost utterly incomprehensible, with a plot so labyrinthine that even a Minotaur would get lost in it. (Famously, not even Raymond Chandler himself knew some of the finer plot points, including who had killed a minor character.) But for all its narrative complexity, The Big Sleep is still stunning cinema, principally because of that all-important chemistry between Bogey and Bacall.

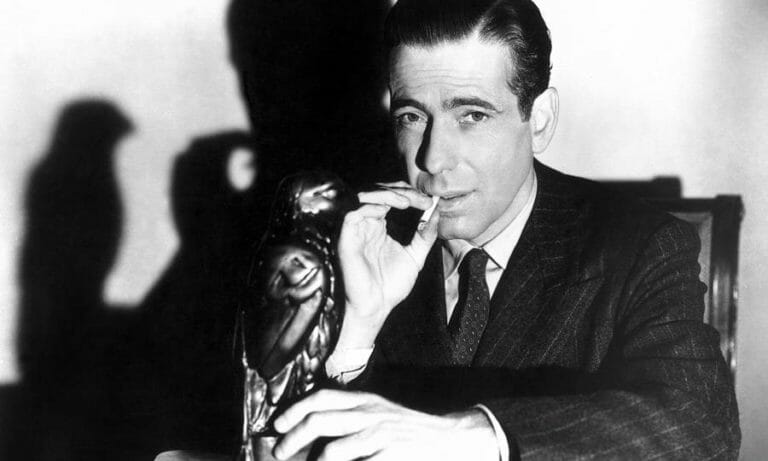

3. THE MALTESE FALCON

(1941, Written and Directed by John Huston, based on the novel of the same name by Dashiell Hammett)

The ur-noir; Bogey’s breakthrough movie (after years of being a supporting or even bit-part player); and the definitive detective movie, just ahead of The Big Sleep. Chandler may now be generally regarded as the greatest detective novelist, ahead of Hammett, but on screen it is Hammett’s Sam Spade who just edges Chandler’s Philip Marlowe, because The Maltese Falcon, while not being an easy film to follow, is infinitely easier to follow and understand than The Big Sleep.

It is almost inconceivable to think of Bogey as a bit-part player, but it’s true: his first screen credit was as “Man in doorway at dance” and he went on to appear in numerous forgettable films in the late 1920s and 1930s, such as The Amazing Dr. Clitterhouse (the only unforgettable feature of which is its title). But that “backstory,” as it were, is surely the key to Bogey’s appeal. He wasn’t beautiful; at the beginning, at least, he could blend into the background as a “Man in doorway at dance.” However, that was also what made him such a perfect screen detective, someone who could go unnoticed in a crowd and spy on others. While Bogey may have gone on to become the most recognisable male face in cinema, at the start, in movies such as The Maltese Falcon, his middle-aged, weather-beaten, almost undistinguished features were what first attracted him to directors such as Huston.

2. IN A LONELY PLACE

(1950, Directed by Nicholas Ray, Written by Edmund H. North and Andrew Solt, based on the novel of the same name by Dorothy B. Hughes)

Bogey is the quintessential man of action, by which I mean actual action (and not just jumping out of exploding cars, as is the case in so-called “action movies” nowadays). He usually played doers – sailors, detectives, war heroes – and yet one of his greatest of roles is as a writer, the very definition of someone who doesn’t do things, but thinks about them and then puts his thoughts down on paper.

The great actress Louise Brooks, the queen of silent movies, wrote a brilliant essay late in life about how the role of screenwriter Dixon Steele In A Lonely Place was Bogart’s best performance, because it summed up all his contradictory qualities: he was both thoughtful and capable of being thoughtless; calm and violent; wild and peaceful. It obviously takes a great movie star to recognise another great movie star, and Brooks nailed Bogart’s brilliance in In A Lonely Place. Perhaps all the while that he was struggling to make it as a star, Bogey was studying the scriptwriters on set as they argued (usually in vain) with their directors, and even when he became a star he would have heard first-hand from Hawks and Huston just how difficult it was to write a script (or at least a good script). Whatever and however, he certainly learned, and then played to perfection, all the vanity and insanity of the writer, especially that most benighted of writers, the Hollywood hack.

1. CASABLANCA

(1942, Directed by Michael Curtiz, Written by Julius J. Epstein, Philip G Epstein, Howard E. Koch and Casey Robinson, based on the play Everybody Comes to Rick’s, by Murray Burnett and Joan Alison)

Perhaps Bogey learned everything he needed to know about writers and writing during the making of Casablanca, the film with seemingly a thousand writers (as the above list of credits suggests). Casablanca is probably the antithesis of the auteur theory, the idea that the best films are the product of a single creator, or “author.” It seems to have no one single author (nor even one single director, as Curtiz was just the last in a long line of directors who worked on it) and yet it is still probably cinema’s most singular vision of freedom, both artistic and political.

At the heart of it, of course, as the title of the original play suggests, is Bogey’s “Rick,” the cynic who eventually proves himself a romantic, but in the process loses the woman he loves. If Casablanca is the obvious choice as the ultimate Bogey movie, well, sometimes the obvious is just absolutely obvious and unarguable. As I have written before, Casablanca is probably the greatest film script ever written, with every line not only beautiful but quotable. However, it would almost certainly never have worked as well as it does without Bogey as the lead.

If all art is at least in part a product of its time, so are all artists. Perhaps it was World War Two that made Bogey the greatest male movie star. Up until its outbreak, he was largely unsuccessful and mostly forgettable in the films he made. With the coming of war, however, and the consequent darkening of mood around the world (even in America before its formal entry to the war after Pearl Harbor), the gangsters and glamour boys of the Thirties no longer seemed to fit the public mood. What was needed instead was an Everyman, but an Everyman who embodied every man’s hope for himself (and every woman’s idealised version of that man). That man, of course, was Bogey, and it is chastening to think that just as some children today no longer know about or understand the importance of World War Two, so they know nothing about the man who was effectively its poster boy. For all true lovers of cinema, though, whatever their age, Bogey will always be the greatest. And it is entirely fitting that, like Christ himself, the King of Cinema was born on Christmas Day.