By Alec Siegel · June 23, 2014

Series Intro

Every art form has its masters, the icons who learned the confines of their art and busted through, paving the way for growth and achievement. Film is no different. For this on-going series, I will be examining, prodding at and dissecting the filmography of a variety of film talent (dead, retired or still active). It’s always interesting to explore the metamorphoses of a legend, and that’s what this series aims to do. The masters didn’t start out as so, so let’s trace the paths taken from rank amateurs to Academy Awards winners.

Stanley Kubrick

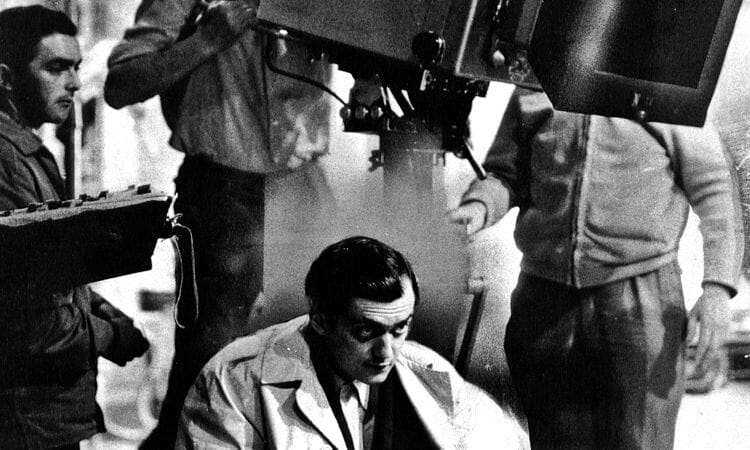

What was a Jewish, Manhattan-born grizzly bear of a man doing living and working in Hertfordshire, England? Well, Stanley Kubrick liked his freedom, he liked being an ocean away from Hollywood, and he liked creative control. But a few decades before he toiled at the Childwickbury Manor (his English abode), hammering away at scripts while ignoring his beard growth, Kubrick was a fresh faced high school graduate, snapping photographs of the New York City jungle on assignment for Look magazine. He had a knack for visual representation, and soon decided to transition from photo-boy to director-man, and thus, a master was born. I’ll be revisiting Kubrick’s storied career as writer, cinematographer, director, producer and editor, a true connoisseur of the art he would help transform. First up, the 1950s, a time of self-discovery and growth for Kubrick as a filmmaker.

Kubrick’s film career began with two 1951 short documentaries, Day of the Fight and Flying Padre. Both are shot in black-and-white and are without dialogue, instead entirely narrated by CBS anchors. Following a photo assignment on middleweight boxer Walter Cartier for Look magazine two years prior, Kubrick decided to feature the Irish-American fighter as the subject of his directorial debut. It was a self-financed effort, and at a budget of $3,900 was later sold at a $100 profit to RKO Pictures for $4,000. The film is exactly as the title suggests, as it shows the monotonous and sometimes maddening routine of a fighter before the night of a fight. Flying Padre is much the same, taking a real life subject, Father Fred Stadtmuller, and shooting a documentary of a day in his life. While Day of the Fight was self-financed, Flying Padre was produced using money that RKO fronted Kubrick and his crew. It’s fascinating to watch these bland, simple exercises, knowing that the man who shot them would later become one of the most revered and influential directors in the history of film. A third short documentary, The Seafarers came in 1953, shortly after the release of his debut feature, Fear and Desire. Like the first two, it was a narrated documentary, a lengthy commercial almost, on the Seafarers International Union.

The brutality of war, what it does to a man’s psyche and its utter ridiculousness, is the subject and theme of a handful of Kubrick’s later films. This preoccupation is first documented on his debut feature film, Fear and Desire (1953), the story of four soldiers from an unidentified nation on unidentified soil fighting an unidentified enemy, which is precisely Kubrick’s point: in war, fear and desire are the only true actors, and the technicalities of national loyalty is immaterial. The film is dialogue heavy without much in terms of story, acting more as a soapbox for Kubrick’s viewpoints rather than a story with characters that demonstrate his ideas. As a foreshadowing of Kubrick’s interest in war’s erosion to rationale, there is a wonderfully directed scene where one of the soldiers (Sidney) watches over an attractive woman who is also a POW. There is a recurrent theme of a man residing on a metaphorical island during war, and Sidney simply self-destructs on his, causing debris and shrapnel to penetrate the islands of his comrades. Fear and Desire is the work of an amateur filmmaker with a lot of ideas, but little experience in how best to express them visually, a skill that will be apparent only a few years later.

There’s a scene in his second feature film Killer’s Kiss (1955) where two characters duel with axes in a room full of mannequins. It’s an absurd, visually arresting scene. Stemming from his days as a youth running around NYC shooting the city’s drab, crumbling inner sanctum, Kubrick flashes his visual acuity with this scene, among others in the film. Killer’s Kiss is a weak story with fairly interesting main characters and an oddly forced happy ending (which Kubrick involuntarily wrote per instruction from United Artists), but shows the blossoming director’s technical improvement with a camera and his eye for striking visual images. It’s an inverse of his previous film, and where that one was heavy on dialogue and not much else, this one has a main character that doesn’t speak until 20 minutes in. With memories of the silent era, Kubrick was raised on images, rather than words eliciting emotion and ideas (a concept he fumbled with his previous film). Killer’s Kiss was a stepping-stone to his finest feature yet that would appear only one short year later.

Signaling the end of Kubrick’s entirely original works (all of his films from this point forward use novels or short stories as source material), The Killing (1956), is a step up in terms of plot and most other elements from his previous films. It was also influential in its use of multiple POVs, where scenes are shown multiple times with fresh perspectives each time. The film is briskly paced, and tells the story of a few mobsters who hire help from the inside of a racetrack they plan to rob. Kubrick shows us the plots; the schemes and the heist itself unfold, which is where the multiple perspectives come in. It was a fresh way to visually tell a story for its time. With The Killing, Kubrick came a long way from uninteresting documentaries and uninspired ramblings on war. The boy with a camera was beginning to mature into a top-notch storyteller and a technical wizard.

Kubrick’s last film of the 1950's was also his best to date. Paths of Glory (1957) is the culmination of Kubrick’s talents to the point of its release, his ability sharper and clearer as the still new filmmaker began to “shoot” his way into America’s conscience. It’s a war film, with the main battlefield being a courtroom and inside the mind of the men who pull the strings during wartime. Gerald Fried, who scored all of Kubrick’s pre-Paths of Glory films, has his best effort here. The actual battlefield scenes, one a reconnaissance mission the other an all out front line assault, are masterfully done. The way he allows the action and facial expressions of his actors to co-exist with Fried’s frantic score is extremely well executed. The film earned several award nominations, the adoration of critics as well as a decent stint at the box office. This newfound success signaled a new era of recognition and box office success for Kubrick, as the 1960's would see the production of many of his most well known films, works that would cement his place in history as one of film's greatest.