By Martin Keady · May 12, 2017

The Story Behind The Screenplay is a new series by Martin Keady that examines the origins of some of the greatest screenplays. It begins with one of the most extraordinary and extraordinarily successful screenplays ever written – Alien.

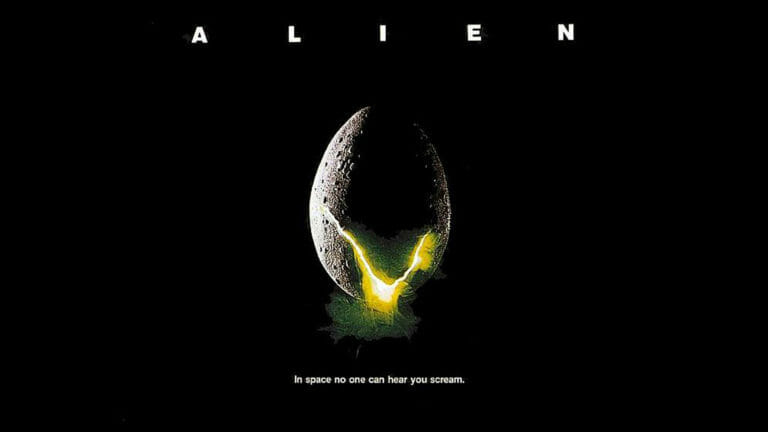

April 26 2017 was “Alien Day”, the second annual celebration of the remarkably successful Alien series of movies, organised by the studio that made them, 20th Century Fox. The very fact that there is an “Alien Day” at all is incredible, given that the original Alien was, in addition to being a sci-fi film, a horror film. There are few other horror films, if any, that have permeated the global cultural consciousness to the extent that they can be considered deserving of such celebration — having their own “day” of the year, like a birthday. However, it is also somewhat ironic, because it demonstrates that the sheer shock and awe that the original film inspired has largely been dissipated. That is a shame, because the original Alien, far more than its seemingly endless succession of sequels and prequels (the latest, Alien:Covenant, will be released within the next few weeks), is simultaneously one of the scariest and most brilliant screenplays ever written.

Like so many sci-fi scripts, Alien began as a short story, co-written by Dan O’Bannon and Ronald Shusett in the mid-1970s. The two men were young sci-fi enthusiasts of the kind who did so much to create the entire sci-fi movie genre, with George Lucas, of course, being the archetype. They had already cut their teeth as film-makers and screenwriters when they began working together. In particular, O’Bannon had attended the University of Southern California film school, where he met a man who would go on to become another giant of the sci-fi genre, John Carpenter.

Carpenter followed in the footsteps of Lucas, who was about a decade older and another alumni of USC, by turning a short sci-fi film he had made at film school into a low-budget but high-concept feature. In Lucas’s case, Electronic Labyrinth: THX 1138 4EB became THX 1138 (1971), his first feature. In Carpenter’s case, the title of his short film, Dark Star, remained the same for the expanded feature, which was released in 1974. O’Bannon had a crucial role in the making of the feature-length version: he co-wrote the script; edited the film; and even played one of the leading roles. Dark Star, dubbed “The Spaced-Out Odyssey”, was that rarity, a sci-fi comedy, about the crew of an intergalactic space-ship charged with the task of destroying unstable planets that might threaten human colonisation of the universe. It was, and remains, a classic cult film, but for all its low-budget brilliance O’Bannon remained dissatisfied, for two main reasons: first, he felt that the alien depicted in the film was poorly, even laughably, realised; and, secondly, he yearned to make a space drama, and ideally a deep space drama (in both senses of the phrase). Eventually, with Alien, he would.

After Dark Star, O’Bannon found work as a jobbing editor and visual effects wizard, skills he had already deployed on Carpenter’s film. In particular, he became attached to an early film adaptation of Frank Herbert’s classic sci-fi novel, Dune, being made by the Chilean director, Alejandro Jodorowsky. Jodorwsky’s version of Dune went unmade (a decade later, the great David Lynch would eventually film the book, making probably the worst and most unsuccessful film of his career) and O’Bannon consequently found himself broke and virtually broken as a film-maker. In desperation, he found himself sleeping on friends’ floors and couches. Fortunately for him, one of those friends was another aspiring sci-fi writer, Ronald Shusett, and in one of their late nights spent chewing the fat and bemoaning their fate they came up with the basic idea for a story called Alien.

Alien succeeds as a story and as a screenplay largely because of its brilliant simplicity. In the far future, the crew of a space-ship (not dissimilar to the one that O’Bannon had helped to create in Dark Star) are awoken from their celestial slumber when they receive a call for help (or so it seems) from a nearby planet. When they investigate, they find only what appears to be a cave full of mysterious eggs. So far, so fascinating, but O’Bannon quickly realised that the biggest problem they had in fully realising the story was in somehow getting one of the inhabitants of these eggs (the titular “Alien”) on board the ship with the human crew, which it would then systematically hunt down and slaughter.

It was Shusett who made the conceptual breakthrough, claiming to have awoken from a dream with the “killer” idea. He duly woke up O’Bannon from his couch or floor and informed him: “Dan, I think I have an idea: the alien screws one of them…it jumps on his face and plants its seed!” To which O’Bannon, having been awoken from his no doubt uncomfortable sleep, replied, “Oh my God, we’ve got it, we’ve got the whole movie!” Even allowing for the use of artistic licence by the pair, the exchange has the ring of truth and is instructive for any screenwriter. So often with screenplays, there is a fundamental problem that has to be overcome, which, when it is overcome, unlocks the whole story. That was certainly the case with Alien.

O’Bannon and Shusett were self-confessed sci-fi enthusiasts (before the terms “nerd” and “geek” ceased to be criticisms and became badges of honour) and so had liberally drawn on many of the great sci-fi stories and films that they had read and seen. As O’Bannon famously put it, “I didn’t steal Alien from anybody. I stole it from everybody!”, which is an amplification of the line variously attributed to Oscar Wilde and T.S. Eliot: “Talent borrows. Genius steals!” However, unlike in so many of those sci-fi stories and films, such as Forbidden Planet (1956), which itself stole much of its plot from Shakespeare’s The Tempest, the extra-terrestrial in Alien was not completely removed and separated from the humans who encounter it. Instead, it becomes literally internalised, first in the crew member that it attacks and then within the confines of the space-ship. In this way, the story and ultimately the screenplay of Alien extended beyond the limits of sci-fi and drew on older, different traditions, particularly those of horror. Just as Dracula (created by Bram Stoker in his classic late 19th century novel) turns his victims into vampires by biting them, so O’Bannon and Shusett’s alien turns the humans it encounters into its host, and then makes the space-ship it escapes into both its home and its hunting ground.

Having worked out how to get the alien on board the space-ship, via the unsuspecting human it has fertilised, O’Bannon and Shusett had to work out how to get it out again, so that it could terrorise and prey upon the other humans. It was here that O’Bannon made his own invaluable contribution to the creation of Alien, by drawing upon painful personal experience and transforming it into something utterly otherworldly and universal.

Throughout his life, O’Bannon had suffered from Crohn’s disease, a disease that causes agonising abdominal pains. Eventually, he would die because of complications arising from the disease, but before it killed him Crohn’s also gave him the inspiration for his greatest creation and what remains the definitive plot device (and when it was finally filmed, the abiding image) of Alien. Shusett had conceived of an utterly unimmaculate conception, whereby the original alien egg would burst open and somehow “implant” itself in one of the crew members. O’Bannon then imagined the fully-grown alien literally bursting out of the crew member’s chest. He always claimed that the pain from his Crohn’s disease was so excruciating that it felt like his own chest or stomach were going to burst open. He took that very painful, indeed almost embarrassing experience and transmogrified it into one of the defining plot devices and images of late 20th century cinema.

Like many of the greatest screenplays, the rest of Alien seemed to write itself. O’Bannon and Shusett completed the story together and then, being sci-fi enthusiasts in the movie capital of the world, they naturally adapted it into a screenplay, with O’Bannon eventually being credited as the sole screenwriter, adapting “a story by” both men. In the wake of Star Wars (1977), with which George Lucas cast aside the relative failure (at least commercially speaking) of THX 1138 to create the greatest fairy tale of the late 20th century/early 21st century, studios suddenly realised that sci-fi could be commercially successful. Consequently, Alien, which was directed by Ridley Scott and released in 1979, became the greatest horror story of the late 20th century/early 21st century.

Alien is a classic film, brilliantly realised on screen by Scott, who was invaluably aided by the visual design of the alien and its world by the great Swiss surrealist artist, H.R. Giger. However, like all classic films, its genesis lay in its script, co-created by two young sci-fi enthusiasts who would draw on their apparently encyclopaedic knowledge of the sci-fi genre (in both literature and cinema) and their own personal experience to produce one of the seminal screenplays. Indeed, given that the alien originally emerges from an egg, it might be better to describe it as the original ovular screenplay.