Sign up for the

TSL Newsletter

and get $50 off Final Draft 12

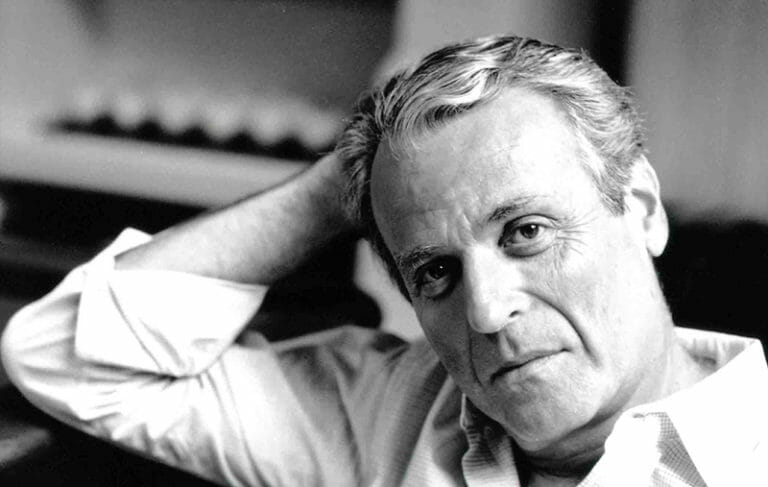

By Martin Keady · June 20, 2017

William Goldman is such a great writer about screenwriting, with his book Adventures In The Screen Trade effectively becoming the screenwriting Bible (and Koran, Torah and Tao), that it is easy to forget that he is a great screenwriter in his own right, having penned several classic movies in several wildly different genres, from Butch Cassidy and The Sundance Kid (1969) to The Princess Bride (1986). It is that ability to walk the walk as well as talking the talk that sets him apart from all other screenwriting gurus, including Robert ‘Story’ McKee. Equally, his keen understanding of the importance of structure in screenwriting (as he himself famously put it, “Screenwriting is structure”) informs his very best scripts.

Like so many great American screenwriters, and as his name implies, Goldman is Jewish. He was born in Chicago in 1935 and his parents were of solid middle-class stock – or so it seemed. His father had been a successful businessman, but eventually succumbed to alcoholism and he ended up taking his own life while William was still in school. Doubtless, the effect on William and his brother, James, who also became a successful author (writing the superb play, The Lion in Winter, about the love affair between King Henry II of England and his wife, Eleanor of Aquitaine), was profound.

Goldman would be the first to dismiss any comparison between himself and greater writers (as he regarded them) who endured childhood tragedy, especially the death or public dissolution of a parent. Nevertheless, it is appropriate that “the Shakespeare of Screenwriting”, as Goldman would come to be called, suffered a similar fate to that of the original Shakespeare. William Shakespeare’s father may not have killed himself, but he was arrested (for usury, or illicit money-lending, and illegal wool trading) and publicly humiliated. In both cases, the destruction or self-destruction of the father helped to create the illustrious writer son.

Goldman always wrote, initially submitting poetry and short stories to college magazines and other publications. Indeed, he was both a successful novelist and playwright before he ever entered the film industry, publishing five novels, beginning with The Temple of Gold (1956), and having a number of plays produced on Broadway. However, it was when he began writing and rewriting screenplays in the 1960s that he finally found his metier.

Like so many screenwriters, Goldman’s first work as a screenwriter was uncredited, when he was hired by the actor Cliff Robertson to adapt a sci-fi novel, Flowers for Algernon, for the screen. Flowers for Algernon, later renamed Charly, was both a successful television drama (in 1961) and then an even more successful film (1968), for which Robertson won the Best Actor Oscar. Telling the story of a man who becomes the subject of a laboratory experiment to raise people’s IQs, it proved Robertson’s signature role (and constant pay check).

Like so many screenwriters, Goldman’s first work as a screenwriter was uncredited, when he was hired by the actor Cliff Robertson to adapt a sci-fi novel, Flowers for Algernon, for the screen. Flowers for Algernon, later renamed Charly, was both a successful television drama (in 1961) and then an even more successful film (1968), for which Robertson won the Best Actor Oscar. Telling the story of a man who becomes the subject of a laboratory experiment to raise people’s IQs, it proved Robertson’s signature role (and constant pay check).

For Goldman himself, however, Charly was an anomaly, because he would later claim that, despite its success, he was utterly incapable of writing sci-fi screenplays, largely because he was uninterested in and ignorant of the genre. Indeed, it is fascinating to consider that in the 1970s and 1980s when, on the back of the phenomenal success of Star Wars, sci-fi almost became the movie genre (and certainly the most successful), Goldman still mainly wrote much more human dramas and often about actual historical events.

His first screenwriting credit was as a co-writer on a fairly undistinguished British comedy, Masquerade (1965), but his first solo screenwriting credit was on the 1966 Paul Newman detective movie, Harper (1966). The film itself is something of a mess, but a fascinating mess, as Newman’s titular private eye investigates the disappearance of a millionaire. Like so many Hollywood movies in the mid-1960s, it attempted to cash in on the new hippy counter-culture that was beginning to emerge and through which Harper trawls in his quest to find the missing mogul.

Harper was almost as complex as The Big Sleep but without Bogey and Bacall’s sheer screen chemistry to make the audience forget about the plot’s pot-holes. However, it at least ended superbly, with Harper being threatened at gun-point by a friend, the attorney who had hired him in the first place. When Harper, who is now virtually suicidal after seeing his marriage end and his career collapse, dares the attorney to shoot him, the attorney is unable to and the film ends on a kind of one-way Mexican stand-off, with the audience wondering whether the trigger will be pulled or not.

In writing Harper, Goldman met and befriended Paul Newman, and it was Newman, along with a then relatively unknown Robert Redford, who would star in the film of Goldman’s first truly great screenplay, Butch Cassidy and The Sundance Kid (1969). It was an original screenplay by Goldman, based on nearly a decade of research into the famous outlaws, who had tried to escape The Wild West by fleeing to Latin America. It was one of the great anti-Westerns that began to emerge at the end of the 1960s (the sine qua non being Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch, which was released just a few years after Butch and Sundance), in which much of the iconography and mythology of the West were subjected to much closer scrutiny than they had been for most of the genre’s history.

Goldman, the most generous of men and writers, always maintained that film-making was essentially a collaborative art-form, as opposed to the idea, in vogue after the French nouvelle vague of the early 1960s, that the best films were individual or even auteur productions. Butch and Sundance is a magnificent vindication of his beliefs, with the subtle but muscular direction of George Roy Hill, the sepia-tinged cinematography of Conrad Hall and the score by Burt Bacharach, including the immortal theme tune “Raindrops Keep Falling On My Head”, all supplementing the wonderful, witty, iconoclastic script. Unsurprisingly, the film cleaned up at the Oscars (with Goldman himself winning the Oscar for Best Original Screenplay) and, infinitely more importantly, almost immediately became the stuff of legend itself.

Goldman, the most generous of men and writers, always maintained that film-making was essentially a collaborative art-form, as opposed to the idea, in vogue after the French nouvelle vague of the early 1960s, that the best films were individual or even auteur productions. Butch and Sundance is a magnificent vindication of his beliefs, with the subtle but muscular direction of George Roy Hill, the sepia-tinged cinematography of Conrad Hall and the score by Burt Bacharach, including the immortal theme tune “Raindrops Keep Falling On My Head”, all supplementing the wonderful, witty, iconoclastic script. Unsurprisingly, the film cleaned up at the Oscars (with Goldman himself winning the Oscar for Best Original Screenplay) and, infinitely more importantly, almost immediately became the stuff of legend itself.

Goldman was in demand as a screenwriter from then on, but he also continued to write novels and other works of literature, abiding by one of his many dictums in Adventures in the Screen Trade that a writer should never just be a screenwriter; they should always be a playwright, novelist, poet or whatever as well, otherwise the misery of seeing so many scripts going unproduced (as was the case with even a successful screenwriter like Goldman himself) would drive them mad. His best scripts of the early 1970s were The Hot Rock (1972), a comedy caper movie about the stealing and re-stealing of a rare African diamond, and The Great Waldo Pepper (1975), about a pilot who misses out on World War One and tries to make amends by flying in the enormous “air circuses” that became popular in America in the late teens and early 1920s.

It was not until the mid-1970s that Goldman would write another truly great screenplay, for which he would eventually win another Academy Award (this time for adaptation, making him one of the few screenwriters to have won Oscars for both an original screenplay and an adapted screenplays). It was All The President’s Men (1976), based on the book of the same name by Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward, the Washington Post reporters who broke the Watergate story. A

As Goldman recounted at length in Adventures in the Screen Trade, the book, like the whole Watergate story, was extraordinarily dense and knotty, necessitating considerable revision and excision before making it to the screen. But as with Butch and Sundance, Goldman essentially boiled the story down to that of two small men (outlaws in the former, journalists in the latter) who become embroiled in something much bigger than themselves (the end of the Wild West in the former, the greatest political scandal of the 20th century in the latter) and through them told a much bigger tale about corruption, disillusionment and eventual salvation.

As Goldman recounted at length in Adventures in the Screen Trade, the book, like the whole Watergate story, was extraordinarily dense and knotty, necessitating considerable revision and excision before making it to the screen. But as with Butch and Sundance, Goldman essentially boiled the story down to that of two small men (outlaws in the former, journalists in the latter) who become embroiled in something much bigger than themselves (the end of the Wild West in the former, the greatest political scandal of the 20th century in the latter) and through them told a much bigger tale about corruption, disillusionment and eventual salvation.

In fact, 1976 was really Goldman’s greatest year as a screenwriter, because that year another one of his finest screenplays, Marathon Man, based on his own novel of the same name, was released and was also a critical and commercial success. This was another story about an ordinary man plunged into something beyond his understanding, as Dustin Hoffman played the titular runner whose secret agent brother is murdered, but not before he can reveal (at least partially) the details of a plot involving a former Nazi torturer, Christian Szell, memorably played by Laurence Olivier.

In Marathon Man’s most famous and now truly iconic scene, Szell uses a dentist’s drill to try to extract the information he wants from Hoffman’s running man (information that he either does not possess or does not wholly understand). As with Butch and Sundance’s famous leap, and Deep Throat, the informer who meets Woodward and Bernstein in an underground car park to pass on the details of the Watergate scandal, Goldman had created another set of memorable characters and images that have seared themselves not only into the history of cinema but the wider culture.

Goldman has written, and rewritten, nearly fifty screenplays, in addition to all his other literary output, which ranges from novels and short stories to memoirs and, of course, books on screenwriting. However, after his fantastically successful run of films from the late 1960s to the end of the 1970s, there are three scripts, each one very different from the others, that really stand out.

The first is The Princess Bride (1987), which was again based on one of his own novels. Just as Butch and Sundance was essentially an anti-Western (or at least a questioning Western) and All The President’s Men was an anti-political movie (that was really a detective story), so The Princess Bride was an anti-fairy tale. Ostensibly the story of a wealthy woman who falls in love with one of her helpers or servants, it is actually an exploration of the whole nature of fairy-tales, and by extension story-telling itself. Like Labyrinth (1986), which was released at almost the same time, it has become one of the most beloved modern children’s movies, meaning that it is beloved by everyone (everyone either being a child or having once been a child).

By complete contrast, Misery (1990), Goldman’s adaptation of the Stephen King novel of the same name, is the dark, claustrophobic story of a successful writer who, after a car accident, finds himself apparently being nursed back to health but in reality imprisoned by an obsessive fan. One of the greatest films about writing and the unhealthy effect that it can have both on its creators and its consumers, it featured another classic Goldman “double-whammy” of memorable characters and unforgettable imagery when the fan, feeling that she has been betrayed by the writer, takes a sledgehammer to his poorly foot, literally knocking it out of shape.

Finally, there is The Ghost and The Darkness (1996), based on the true story, recorded in The Man-eaters of Tsavo by John Henry Patterson, of Patterson’s involvement in the building of an East African railway line that was stalked by two man-eating lions. They were nicknamed ‘The Ghost and The Darkness’ because of their apparently supernatural ability to disappear into the night and then reappear elsewhere in the night, claws bared and teeth unleashed.

Adventures in the Screen Trade was first published in 1983 and in it Goldman writes movingly of his long-held desire to write a screenplay based on the book, which he describes as one of the most truly cinematic stories he had ever read. However, by the time his screenplay was finally filmed, nearly 15 years later, the lamentable Val Kilmer had been cast as one of the leads, alongside Michael Douglas, and after the Newman/Redford, Redford/Hoffman and Hoffman/Olivier double-bills that had been at the heart of his great 60s and 70s films, it was a case of from the sublime to the ridiculous. The resulting film was a worthy effort, but Kilmer’s presence alone was enough to deny it the magnificence that Goldman had long hoped for.

It was precisely that kind of story that Goldman had written about so beautifully and humorously in Adventures in the Screen Trade, in which he recounts several tales of how promising screenplays are often completely undermined by appalling casting decisions. He cites the casting of Nanette Newman in The Stepford Wives (1975) by the director, Bryan Forbes, who was also her husband, as another classic example of how poor casting can fatally weaken otherwise intriguing films. It was exactly that kind of insider storytelling, by a man who had made his fortune and name in the film industry, that made Adventures in the Screen Trade so successful, and popular. However, its real value is the advice that it gives to other screenwriters.

Among many other things (a memoir of his own screenwriting career, a ‘how to guide’ for aspiring screenwriters, an analysis of the mechanics and finances of the American movie industry), Adventures in the Screen Trade is the finest collection of maxims about the movies ever written, so many of which have entered not only the cinematic lexicon but the entire cultural discourse.

“Nobody knows anything”, the aforementioned “Screenwriting is Structure” and “First drafts are always shit” are just three examples of Goldman’s unsurpassed ability to condense hard-learned truths from the coalface of the film industry down into memorable phrases or sayings, and it is the absence of similarly memorable maxims that is arguably the biggest failing of his subsequent book on screenwriting, Which Lie Did I Tell? Ultimately, Adventures, along with his scripts for classics such as Butch and Sundance, All The President’s Men, Marathon Man and Misery, will be his legacy, making him a truly singular figure in the history of screenwriting – the only man who could both teach screenwriting and write great screenplays.