Sign up for the

TSL Newsletter

and get $50 off Final Draft 12

By Martin Keady · December 7, 2017

Paul Schrader was probably the greatest screenwriter, and certainly the most famous screenwriter, of the late 20th century. The man who wrote the greatest and most famous single line in modern cinema (“You talkin’ to me?”) almost came to embody the idea of what a screenwriter should be: self-sufficient; obsessive; and prepared, if necessary, to put a gun to his head to force himself to write (as Schrader himself was reputed to do early in his career). If, ultimately, his film-making career followed the classic trajectory of so many great screenwriters – early struggle, eventual breakthrough and, finally, slow decline – the two magnificent screenplays that he wrote for Martin Scorsese, Taxi Driver and Raging Bull, alone justify his place in the screenwriting pantheon.

Schrader is unique among all the screenwriters in this series in that he did not grow up watching movies. In fact, his strict Calvinist father forbade him from seeing films while he was a child, so much so that Schrader claims that he only saw his first film when he was 17 years old. Even then, he could not completely escape the confines of his upbringing, as he attended the aptly named Calvin College in his home town of Grand Rapids, Michigan, and studied theology. He was only able to flee from Calvinism and Michigan when he moved to Los Angeles to take an MA in Film Studies at UCLA. Even there, however, and throughout his writing career, he never completely escaped the shadow of Calvinism, the strictest and most ascetic form of Christianity, which is almost a form of Christian fundamentalism. Its central tenet of predestination – that however hard we try, we cannot escape our fate – is there in his greatest screenplays, even if his characters never set foot inside a church.

Schrader is unique among all the screenwriters in this series in that he did not grow up watching movies. In fact, his strict Calvinist father forbade him from seeing films while he was a child, so much so that Schrader claims that he only saw his first film when he was 17 years old. Even then, he could not completely escape the confines of his upbringing, as he attended the aptly named Calvin College in his home town of Grand Rapids, Michigan, and studied theology. He was only able to flee from Calvinism and Michigan when he moved to Los Angeles to take an MA in Film Studies at UCLA. Even there, however, and throughout his writing career, he never completely escaped the shadow of Calvinism, the strictest and most ascetic form of Christianity, which is almost a form of Christian fundamentalism. Its central tenet of predestination – that however hard we try, we cannot escape our fate – is there in his greatest screenplays, even if his characters never set foot inside a church.

In the early 1970s, while he was still studying film, Schrader began writing about it, for publications including Los Angeles Free Press and Cinema. He received encouragement in his early, fledgling criticism from the woman who was arguably the greatest American film critic of all, Pauline Kael, and wrote a well-regarded book about three of his favourite directors, Transcendental Style in Film: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer, which was published in 1972. Even in this venture, however, the influence of Schrader’s Calvinism could be felt, as probably the greatest similarity between Schrader’s “holy trinity” of film-makers was what could be described as their “Cinematic Calvinism”, which emphasised rigour, discipline and artistic endeavour over such trifling and determinedly un-Calvinistic qualities as entertainment, humour and light-heartedness.

Schrader may have remained a film critic rather than a film-maker but for the influence of Ozu’s home country, Japan. Film criticism couldn’t pay all the bills, so for a time in the early 1970s Schrader lived and worked in Japan, teaching English among other things. He drew on that knowledge of Japan to write his first screenplay that sold, The Yakuza (1974), which he co-wrote with his brother, Leonard. In fact, it sold for an awful lot of money – reportedly for more than $300,000, which was a staggering sum for a first-time screenwriter (or even a pair of screenwriters) in the early 1970s.

The Yakuza was directed by Sydney Pollack (it was one of his first major studio films) and starred Robert Mitchum, by then in his fifties, as an American returning to Japan after years away to try and help an old friend find his missing daughter, a search that leads him into the then largely unknown (at least in the West) world of the Yakuza, or the Japanese Mafia. As the tagline for the film put it, “100 years ago, they would have been Samurai”. Certainly Schrader was fascinated by these Japanese gangsters, who differed from Western gangsters in many respects, not least their adherence (or at least notional adherence) to the kind of strict personal discipline that was not a million miles away from the strict Calvinism of Schrader’s childhood. However, despite the impeccable credentials of both the director and the lead, not to mention a rewrite by Robert Towne, The Yakuza failed commercially, probably because American audiences were obsessed in the early to mid-1970s with the Italian-American gangsters that Francis Ford Coppola was genuinely depicting for the first time in The Godfather (Parts I and II).

Nevertheless, the money he made from selling the script for The Yakuza set Schrader up for a screenwriting career and after ditching his brother as a co-writer and going it alone, he soon began writing about his home country, America. In particular, he examined how America was struggling to recover from the loss of the Vietnam War (the first major overseas war that America had ever lost) and the subsequent humiliating retreat from Saigon. All of the attendant feelings of disgrace and unworthiness, which again are classic Calvinist traits, went into his script for Taxi Driver (1976) and the characterisation of the greatest loner in cinema, Travis Bickle.

Nevertheless, the money he made from selling the script for The Yakuza set Schrader up for a screenwriting career and after ditching his brother as a co-writer and going it alone, he soon began writing about his home country, America. In particular, he examined how America was struggling to recover from the loss of the Vietnam War (the first major overseas war that America had ever lost) and the subsequent humiliating retreat from Saigon. All of the attendant feelings of disgrace and unworthiness, which again are classic Calvinist traits, went into his script for Taxi Driver (1976) and the characterisation of the greatest loner in cinema, Travis Bickle.

One of the hardest things to depict in cinema is loneliness, or more precisely the state of being alone. Because of cinema’s natural leaning towards realism (cinema, more than any other art-form, literally captures reality, but equally finds it hard to escape reality) and its natural propensity (since the invention of the “talkies”, at least) towards dialogue, it is extremely hard to portray someone who spends most of their time on their own, as Travis does.

Perhaps the most famous example of a film that shows this difficulty is one of Billy Wilder’s least successful films, The Spirit of St Louis (1957), which tells the story of Charles Lindbergh’s first transatlantic flight. Because Lindbergh was alone in the cockpit on his solo quest, Wilder came up with the conceit that he would talk to a fly, the only other living thing in the plane. (A more modern example would be the volleyball that Tom Hanks talks to in 2000’s Cast Away.) Wilder himself later admitted that the whole conceit was ridiculous and badly damaged the movie.

Schrader overcame this difficulty by having Travis talk to himself, most famously when he is trying out his newly purchased handguns, with which he intends to track down and kill the pimp (played by Harvey Keitel) who is mercilessly exploiting Jodie Foster’s child prostitute. As he tries out his various firearms, Travis (who is played both beautifully and terrifyingly by Robert De Niro) talks to himself in the mirror: “You talkin’ to me?…You must be, because I’m the only one here.” It worked wonderfully, to the extent that this one scene has become probably the most copied, mimicked and parodied in modern cinema. And as Schrader later admitted, it had a lot to do with the sheer hard grind of being a screenwriter (or any other kind of writer), who, by definition, spends most of their time alone.

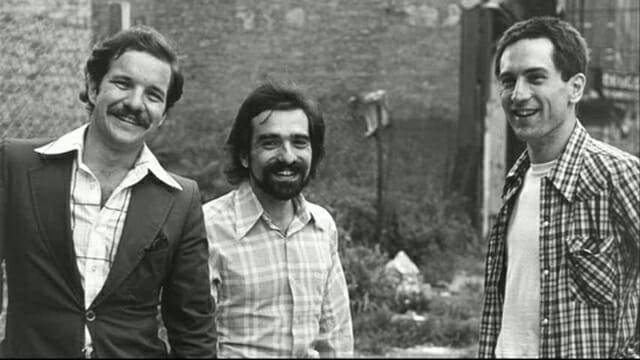

Taxi Driver was an enormous hit, both critically and commercially. It became the breakthrough movie for director Martin Scorsese, allowing him to build on the cult status he had gained from earlier movies like Mean Streets (1973); for De Niro, who was already a star after The Godfather Part II but, until Taxi Driver, had not been a bankable lead; and for Schrader himself. It won the Palme D’Or at Cannes and earned an Academy Award nomination for Best Picture in 1977, one of the most legendary years for the Oscars, as it was up against other instant classics such as All The President’s Men and Network. Sadly, ridiculously, they all lost out to Rocky.

Taxi Driver was an enormous hit, both critically and commercially. It became the breakthrough movie for director Martin Scorsese, allowing him to build on the cult status he had gained from earlier movies like Mean Streets (1973); for De Niro, who was already a star after The Godfather Part II but, until Taxi Driver, had not been a bankable lead; and for Schrader himself. It won the Palme D’Or at Cannes and earned an Academy Award nomination for Best Picture in 1977, one of the most legendary years for the Oscars, as it was up against other instant classics such as All The President’s Men and Network. Sadly, ridiculously, they all lost out to Rocky.

It was another, infinitely more realistic and infinitely better boxing film that was the second and last great collaboration between cinema’s new “holy trinity” of Scorsese, De Niro and Schrader. That film was Raging Bull (1980). A biopic of the legendary and legendarily self-destructive boxer, Jake LaMotta, Raging Bull was based on LaMotta’s autobiography of the same name, which was adapted by Schrader and another writer, Mardik Martin, a close friend of Scorsese’s who had helped Scorsese to write his early films, including Mean Streets.

As they share essentially the same creative team, it is fascinating to think of Raging Bull as a kind of sequel, or more accurately prequel, to Taxi Driver. Like Taxi Driver, it focuses on a solipsistic man who finds it almost impossible to communicate with others (unlike Schrader himself, who is one of cinema’s greatest raconteurs). However, whereas Travis Bickle was a fictional, unknown Vietnam vet before he goes on his redemptive killing spree, Jake LaMotta was not only real but famous, for his ability to use his fists.

Unfortunately for him, he is unable to control where and when he uses them, to the extent that he becomes a wife-beater. As his life, like that of Travis, spirals out of control, he ends up a washed-up has-been, struggling to make a living by singing and telling stories about his boxing career (doing both pretty badly), until he finally begins to turn his life around by writing about it. Once again, for all the obvious differences between Schrader and LaMotta, this is an obvious point of similarity, in that Schrader, who replaced religious obsession with a series of debilitating substance addictions, ultimately saved his own life by writing about it.

However, nothing that Schrader wrote after Raging Bull, which, like Taxi Driver, was nominated for the Best Picture Oscar (and, like Taxi Driver, lost out to a far inferior film, Ordinary People), came close to matching the brilliance and sheer impact of the two masterpieces he wrote for Scorsese. That was partly because Schrader no longer regarded himself purely as a screenwriter and instead became a writer-director. Some of the films he directed, notably Hardcore (1979), in which George C. Scott searches for his missing daughter and finds her in the world of explicit pornography (a plotline similar to that of The Yakuza), and Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters (1985), an avowedly artistic biopic of the Japanese writer, were fascinating. However, none of them, with the exception of American Gigolo (1980), in which Richard Gere played a male escort who becomes the main suspect in a murder case, were particularly successful commercially.

Schrader, who is now 71, still directs, with his latest project, entitled The Jesuit, likely to have a religious theme as well as a religious title. However, nothing that he writes or directs now is likely to have the same power and clout as his classic one-two pair of punches with Scorsese, Taxi Driver and Raging Bull. In those two movies, he effectively created a new kind of American hero, or more accurately anti-hero: a man alone, who is trying to survive in a world that he thinks is trying to kill him (and in Jake LaMotta’s case literally is trying to kill him, in the boxing ring), but who ends up nearly killing himself before somehow surviving, albeit in a drastically reduced state. In this regard, both Travis Bickle and Jake LaMotta are almost autobiographical creations.

For all the latest from The Script Lab, be sure to follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.