By Jim Rohner · April 4, 2011

Recently my roommate and I re-upped at the apartment where we've been living since last April after our landlords offered us another year for $200 less per month. We were happy to accept the offer; after all, it was a mutually beneficial them (they didn’t have to find new renters) and us (we'd be saving money, and most importantly, we didn't have to physically move anywhere).

Anyone who's ever moved can relate to thinking that there's no bigger pain in the ass on this earth then packing up everything you own, transporting it in piecemeal fashion from Point A to Point B, then unpacking and re-dressing everything in a futile effort to duplicate the physical and emotional groove to which you'd become so accustomed.

Imagine how much more monstrous it would be to move into a new place if you had a newborn daughter to go along with two young boys and one of those boys was so fluent in astral projection that he leaves his body every night during his sleep, and during one of those trips, he gets lost in the spirit world because demonic forces are jealous of the physical form he's left back in the physical world. Sounds like it could exacerbate an already stressful situation, right?

That's the predicament Josh Lambert (Patrick Wilson) and his wife, Renai (Rose Byrne), find themselves in after they move into a new house and their son, Dalton (Ty Simpkins), slips into a coma that medical science cannot explain. Sure, the rapscallion took a tumble from a ladder in the creepy attic, but the blow to his head doesn’t explain why quite comatose even though he displays all signs of consciousness. There's nothing wrong with the body, but the soul seems MIA.

Not just MIA, but being held captive according to Elise Rainier (Lin Shaye), a medium with connections to Josh's past who's called in to help the couple after a second move fails to solve the disturbances: disembodied footsteps, doors that open by themselves, and figures that torment Renai during Josh's increasingly frequent late nights at work. With Elise's help, the Lamberts uncover the demonic connection keeping Dalton imprisoned – "the man with fire on his face" – and they chart a course to bring their son back.

You may notice a lot of similarities to Poltergeist in the description of the Insidious narrative, and it wouldn't be entirely off base to compare the two in both concept and quality. Both films feature paranormal torment that manifests upon the arrival in a new home, and the cores of both hinge on the emotional journey of loving families. Both films also do a damn fine job in scaring the bejeezus out of us. There are no moments in Insidious that come close to that of the clown doll in Poltergeist, but director James Wan shows quite the proficiency in how he diversifies the terrifies to keep the audience on edge. Aside from the dime a dozen loud-noise-holy-shit-there's-something-where-there-was-nothing-before-jump-scares, Wan keeps things interesting with the slow buildup frights that find us begging for something to happen already, those subtle scares that leave us asking, "Holy shit, did I just see what I thought I saw?" and even some false scares that build up to nothing except a scene cut. Considering Wan's past work has been higher concept than this, it's admirable, considering how effective he's able to craft atmosphere and mood.

However, a look beneath the surface of Insidious reveals a lot of problems that prohibit the film from being appreciated any deeper than superficially. The film's got plenty of scares, but it has to fake its way through heart and soul. There's a family at the center of Insidious, but emotional engagement with them is difficult, partly due to the stiff performances Wan gets from Byrne and Wilson, and in addition, because of the missteps Whannell took with the script.

Being that Renai is a stay at home mom, clearly the supernatural forces are going to torment her the most and thus, for the first half of the film, Insidious belongs to her. But then halfway through, a tenuously crafted backstory involving Josh takes over and a character who has been largely peripheral suddenly takes the spotlight, whereas the one with whom we've connected gets pushed aside. By that time, knowing as little about Josh as we do, the plot development takes a jarring 180 degree turn, which leads to an ending that is infuriatingly out of sync with everything that came before it, seemingly motivated entirely by a marketing department arguing for sequel potential.

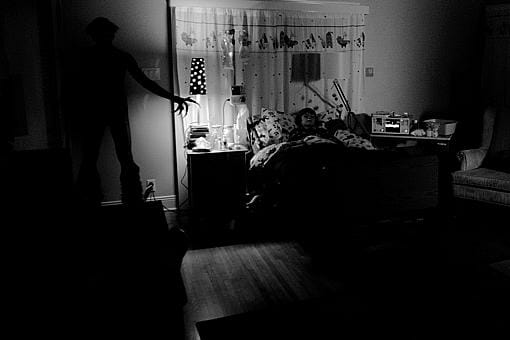

Not helping Insidious' cause is the fact that Wan seems to suffer Wes Craven Syndrome in which he's better at directing mood than action. Insidious is most effective when Josh is walking through The Further, the foggy, Silent Hill-esque astral plane where he can only see as far as his lantern allows him to. Unfortunately, Wan can't seem to help but insert himself into the film with a pivotal sequence shot in his characteristic schizophrenic aesthetic with its sped up camera, double exposures and quick, flashy cuts. It's distracting and incongruous and not the last time in the film that Wan almost torpedoes all the good will he had previously built up by demonstrating a weakness with tonal inconsistency. The film serves up its best work when the scares are held at arms length – a laughing child runs by in the background, a front door is widely ajar seconds after it's been closed and locked, the demonic force is glimpsed only in the shadows of night – but come Act III, Wan and Whannell seemed to have grown impatient with the "less is more" mentality and jammed it full of visuals and set pieces that are better served for another film entirely.

None of this is enough to make Insidious a bad movie, but it's certainly enough to hold it back from being anything great. Almost three decades later, Poltergeist still rises above its genre as a time-tested classic. Three decades from now, conversely, Insidious will be dead, only remembered as just another flick from the guys who brought us Death Sentence and Dead Silence. And so it goes…