By Brock Wilbur · November 28, 2011

The biopic is a strange device: the retelling/re-imagining of a human life, condensed into an hour and thirty minutes, wherein actors must become not a character, but rather a human being who once existed. Stranger still when making a biopic about the life of an actor, because you're instantly several more layers deep in terms of the identity you're supposed to focus on. This is probably why the phantasmagorical The Life and Death of Peter Sellers and All That Jazz became the unbeatable champions of this genre, due to refusing to limit their scope to, even to just reality. But My Week with Marilyn is, regretfully, not that kind of film. It is another story behind the story behind the story of an actress who was not famous for acting. A woman whose life has been covered to death. Literally.

While I am so loathe to ask this question (as someone who recently pronounced their love for Tucker & Dale vs Evil), but what is the point of this movie? Monroe has been portrayed as the focus of biopics more than a dozen times, with a (second) adaptation of Joyce Carol Oates' Blonde starring Naomi Watts in post-production now. But with no major revelations about the star herself and no daring choices about production or portrayal, for what purpose was this film made?

To win Michelle Williams an Oscar. Which she probably will. And launch the career Eddie Redmayne, much to the displeasure of Kip Pardue.

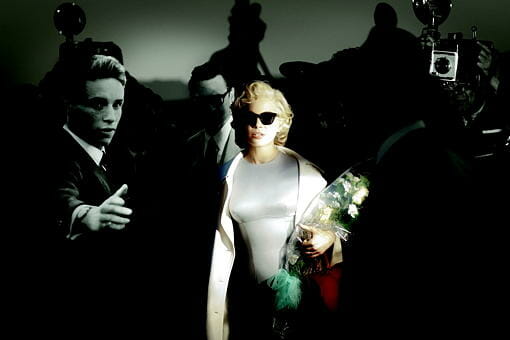

Redmayne plays Colin Clark, a recent Oxford graduate who uses family connections to land his first film industry role as 3rd Assistant Director for Laurence Olivier (Kenneth Branagh). The picture is The Prince and the Showgirl, and it collapses inward upon the arrival of the biggest star in the world: Marilyn Monroe. Olivier's theatrical direction and tyrannical control reduces Monroe to a stuttering mess, and it falls upon her agent (Dominic Cooper) and her acting coach Paula Strasberg (Zoe Wanamaker) to put her back together again. When her new husband Arthur Miller (Dougray Scott) leaves the country, Monroe seeks refuge for one week with the lowly errand boy, who might be the only person truly on her side.

The film is well made and features an exceedingly strong cast, also including Judi Dench, Julia Ormond, Emma Watson, and Derek Jacobi. But it's all a bit of a mess beneath the surface. And no, I do not think that was a clever structural joke for a Monroe biopic.

Williams does excellent work with every minute she's on screen, but she's not on screen nearly enough. Framing the story around Colin Clarke (it is based on his book and diaries after all) is a fine choice, since it would be difficult to show the world through Marilyn's eyes when she spends portions of the film catatonic. That also means this is Colin's story about Colin, and while it means we get to see Strasberg on bended knee praising Monroe as a God or Olivier and his wife falling out over his new lead actress, these little behind the scenes glimpses do little more than cast Colin as a snoop, rather than a character who learned and evolved from what he took in.

This isn't to say they've chosen the wrong protagonist. The only perspective on Monroe is that of an outsider, since she never let anyone in, and a young, love-struck boy witnessing the surprising level of control she wielded versus the control she did not makes for a more interesting film than some omniscient perspective of her private battles. But it does mean that there is a surprising amount of "My" in My Week With Marilyn, and it deflates the audience by the end.

But to make a case for "Why", I think the answer lies in the film's "We". Near the mid-point, Olivier is at his breaking point and explodes on Clark and the agent in private:"Teaching Marilyn Monroe to act is like teaching Urdu to a badger!" But once the agent departs to calm her with more medication, Olivier is left to fume in his predicament of an actress who can neither act nor be natural, directed and controlled by a multiple of people, and consistently kept sedated for fear her hangers-on could lose their golden goose. Clark attempts to defend her team as the only family or friends she's ever had.

While Olivier balks at this, the portrayal of life by committee is perhaps the hidden thesis that delivers on a relevant purpose. Certainly, much of Monroe defines the proto-celebrity, and the central fight between her and Olivier is even called out as the fight between the old and the future. But it was Clark calling them a "team" that defined this as a moment Hollywood, and our society as a whole, would never recover from. Teachers, gurus, guides, life-coaches, partners, lovers, friends, and fans: All elements of a machine designed to bleed you dry while making you feel empty without them. And Collin, whether he admits it or not, is just another cog. Watching this submission reconstructs the events in a global perspective, as if the dying star implosion of Monroe were the klaxon sounding for all western civilization; each tear not for herself, but for the world she would leave in her wake. As if somehow the fabric of time were pulled back just enough for Monroe to glimpse the future, and know that her existence would allow for the creation Kim Kardashian, Tila Tequila, and one million others who pined for a reality they could construct, but never fully embrace.

It was also this moment where I wished so desperately that Lindsay Lohan was insurable, so that she might have taken this part. She would not have done it better, but she's lived it and may one day work through it. While I believe the genuine emotion of every slight gesture Williams gave us, Lohan doing one tenth as good would have still brought such honesty it would have left audiences in awe.

So perhaps that is the singular failing of My Week With Marilyn that leaves you glad to have seen it, but not ready to throw a parade in it's honor: There's no risk. No boundary was pushed, and as a (middle-of-the-road) Marilyn fan, no new information was given. Between the lines, I can read apocalyptic stakes, but they aren't on the screen. There are no stakes at all. The script shoots just low enough to deprive Michelle Williams the performance of a lifetime, and the rest of the film (especially the ending) seems designed purely for award season fodder. It's hard to fault a good film for being too generic, but when you can't shake the presence of an implied Harvey Weinstein instructing you to approve, something in you fights back.

The Weinsteins can't force you to love. Monroe could. Maybe that's why this movie was made.