The American: In Case You Had Forgotten, Films Can Be Subtle

By Peter Wertz · September 6, 2010

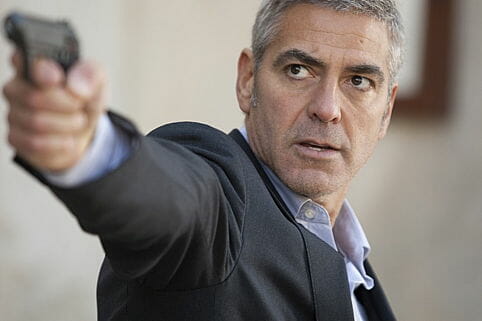

There’s something poetic about The American opening next to Machete, Robert Rodriguez’s latest explosion of cheeky violence. And Machete is certainly not the only case of superfluous violence in recent memory. The Expendables, Piranha 3D, The A-Team, even Kick-Ass way back in April. Film this summer hasn’t had much interest in subtlety or consequences. Meanwhile Anton Corbijn’s The American is quietly released, it’s trailer ambiguous and cerebral, it’s only apparent draw for the average movie-goer: a shirtless George Clooney. After an assault of films who hope to stay unrelentingly in your face for a full two hours, The American gently hopes only to do the next best thing: stay in your mind.

The American Jack (Clooney) is the archetypal assassin; traveling the globe and speaking in grunts. When his solitude is broken and he’s forced to kill the woman he’s taken up with, Jack makes his way to Rome. His contact there and presumably the man Jack works for is named Pavel (Johan Leysen), and his disappointment is fully apparent at all times. Despite Jack’s proficiency it seems inevitable that Pavel will have no choice but to try and kill him. This is the world these men live in. Jack is sent to hide away in a small and picturesque Italian village, where he befriends a priest (Paolo Bonacelli), falls for a prostitute (Violante Placido), builds a super gun for a fellow assassin (Thekla Reuten) and senses the constant presence of a Swedish killer (Samuli Vauramo). All in a row these plot points give the impression that the film is perhaps convoluted or heavy on narrative, but that’s really not the case. The American is clean, and small, and at times… kind of boring.

Regardless of anything else the film does well, it establishes setting and tone masterfully. Mostly Corbijn seems preoccupied with mood, and mostly he does a fine job of distilling the environment into its sensory elements. Footsteps echo through the stone walls of this Italian villa and shadows bleed out of every corner, keeping Jack’s head on a constant swivel. It’s this omnipresent sense of conspicuousness that I believe leads to the title of the film. Jack’s Americanism is constantly recognized and referred to, and for a man so concerned with lying low, this is far from helpful.

Though it may be described as a thriller, The American is far more tense than frightening, and Clooney does an excellent job of navigating Corbijn’s Hitchcockian climate. But I’m an audience member who has become desensitized to the struggle of killers, and this is purely exemplified when, in the first three minutes of the film, Jack shoots an innocent woman in the back of the head. It may not be viciousness or evil, but a world where these kind of choices are no longer choices. But this film has much the same dilemma as any film about a man who has dug his own grave. While I viscerally may feel the tension, I’m not cognitively invested in Jack’s well-being, and this disconnect leads to apathy and, eventually, boredom.

The film attempts to quench this ennui with a poorly developed love story and the prostitute Clara as Jack’s light at the end of the tunnel. Her genuine affection and interest compels Jack to do what all protagonist spy/assassins eventually must try to do: get out of the game. But of course there’s no happy ending, because there’s never a happy ending and as much as The American might feel unique to this season’s celluloid lineup, it absolutely requires of the viewer a history of spy thrillers. When Jack tells Pavel he wants out, you know precisely what the message will be in Pavel’s subsequent phone call. It keeps the viewing simple and not at all surprising.

Which raises the question of whether or not a twist is even necessary. Filmmakers often seem so caught up in keeping their project unique that the presence of twists and turns and monkey wrenches is never questioned. Certainly they can provide a much-needed jolt to a dead script, but they can just as easily convolute. The American is the case where a simplified story based in mythology and archetype is preferable to an attempt at something new. This is mainly because The American is not an action film. It’s a character study. A man who has spent years (presumably) killing and an analysis of his remorse. Is it real or a product of consequence? Is this potential future genuine, or is he simply repeating history. Certainly the film’s opener, with Jack and a beautiful woman holed up in a cabin becomes familiar as we see his relationship with Clara develop. Jack’s remorse for killing his former lover seems genuine, but so does his love for Clara, and anyone paying attention can see that for what it truly is: a reaction to a sexually-charge connection and the pursuit for more. As much as we may want to believe that Killer Jack is capable of being something other than what he is, it certainly doesn’t seem realistic. His ruthlessness may have been built into him, but it’s there nonetheless.

Plenty of reviewers will have no problem dogging the simplicity of The American, calling it slow and exhausting and forgettable. While they won’t be entirely wrong, they will have missed the point. This is not a summer movie and it’s not meant to sit next to Machete on the marquee. This is a thoughtful and tense, well-acted and lovingly shot piece on the character of a man for whom killing is NOT easy. Anytime our hero is a murderer, the killing he does is simply a means to an end, but what keeps The American an exception, what makes this film unique in a truly gratifying way is the way it reminds its audience that, despite everything else you may have seen or heard to the contrary, killing a human being is not fun, or good, or easily forgotten.

2.5 out of 4 moody murders.