By Martin Keady · June 24, 2019

Famous Screenwriters is a new series by The Script Lab for 2019, in which our resident cinema historian, Martin Keady, looks at the great screenwriting cities of the world – those that have produced many of the world’s greatest screenwriters. He has previously covered London, New York, Los Angeles, Boston, Houston and Toronto.

For Part 7, he looks at Sydney, Australia’s largest city and home to (or at least staging post for) many of Australia’s greatest screenwriters.

For much of the 20th century, Australia, including Sydney, remained something of a backwater in global terms: in sport (it was only from the 1980s onwards that all the great non-Australian tennis players started attending the Australian Open); in literature and the arts generally (in which there was the famous “cultural cringe”, or deference to the supposed mother country, Britain); and in cinema in particular (as reflected by the relatively small size and output of the Australian film industry). Then, from the 1960s and 1970s onwards, a new breed of writers and artists, including filmmakers and screenwriters, from Germaine Greer to Peter Weir, began putting Australia firmly on the global cultural map.

As with every city in this series, not all of the writers on this list were born in Sydney, but all of them have a strong cinematic connection with the city; if they weren’t born there, they studied there, lived there or wrote films that were set or shot there. In the process, they all helped to establish the cinematic profile and legacy of a city that is simultaneously the epitome of the old Australian pioneer spirit and one of the truly great world cities of the 21st century.

Here are 10 Sydney screenwriters.

Films truly are like buses: just as you can wait ages for a bus and then they all come along at once, so audiences can wait for ages for a film on a particular subject and then two (or more) films on that subject arrive almost simultaneously. That is certainly true of films about the controversial subject of “gay conversion therapy”, because soon after the release of The Miseducation of Cameron Post (2018), which looks at the subject from the point of view of a teenage girl, there has come Boy Erased (also 2018), which tells the story from a male point of view.

Films truly are like buses: just as you can wait ages for a bus and then they all come along at once, so audiences can wait for ages for a film on a particular subject and then two (or more) films on that subject arrive almost simultaneously. That is certainly true of films about the controversial subject of “gay conversion therapy”, because soon after the release of The Miseducation of Cameron Post (2018), which looks at the subject from the point of view of a teenage girl, there has come Boy Erased (also 2018), which tells the story from a male point of view.

Download the script for Boy Erased here for free.

The writer and director of Boy Erased is Joel Edgerton, the Sydney-educated actor and filmmaker. As an actor, he has been one of the most successful Australian exports since Russell Crowe and Heath Ledger, appearing in major Hollywood films such as Zero Dark Thirty (2012), Baz Luhrmann’s The Great Gatsby (2013) (in which he was particularly good as Daisy’s unfaithful and ultimately vengeful husband, Tom Buchanan) and Black Mass (2015). As a screenwriter, he helped to develop the story for The Rover (2014), a contemporary Australian “Western” (or, more accurately, “Southern”); he wrote and directed The Gift (2015), a psychological drama about a man (played by Edgerton himself) who emerges from a couple’s past to terrorize them; and he co-wrote the screenplay for Jane Got A Gun (2015), an actual Western, but with a gunfighter who is female

Download the script for ZERO DARK THIRTY here for free.

KEY SYDNEY (OR AT LEAST AUSTRALIAN) WORK: THE ROVER (2014)

Nick Enright died in Sydney in 2003, when he was only 52 years old, but in just over half a century he had enjoyed enormous success as a writer in a wide range of fields: as a playwright, including Blackrock (1995), which was based on a real murder in Australian suburbia; as a writer and lyricist for musical comedy, including The Venetian Twins (1979), which was an updating of Carlo Goldoni’s classic 18th century commedia dell’arte play; and as a screenwriter, including on a film adaptation of Blackrock (1997) and, most famously, as the screenwriter of Lorenzo’s Oil (1992).

Nick Enright died in Sydney in 2003, when he was only 52 years old, but in just over half a century he had enjoyed enormous success as a writer in a wide range of fields: as a playwright, including Blackrock (1995), which was based on a real murder in Australian suburbia; as a writer and lyricist for musical comedy, including The Venetian Twins (1979), which was an updating of Carlo Goldoni’s classic 18th century commedia dell’arte play; and as a screenwriter, including on a film adaptation of Blackrock (1997) and, most famously, as the screenwriter of Lorenzo’s Oil (1992).

Lorenzo’s Oil is the most successful non-Mad Max film made by George Miller, the creator of the Mad Max series of films that first made Mel Gibson a star and, more recently, have been spectacularly “reanimated” with Mad Max: Fury Road (2015). In contrast with all the “sturm and drang” of the Mad Max series, Lorenzo’s Oil is a genuinely moving family drama based on the true story of a couple who experience every parent’s worst nightmare, namely that their child is diagnosed with a seemingly incurable illness, but somehow they set out to find a cure. Enright and Miller co-wrote the script, for which they were nominated for an Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay.

KEY SYDNEY WORK: COME IN SPINNER (1990), A TELEVISION ADAPTATION OF THE 1951 NOVEL OF THE SAME NAME BY DYMPHNA CUSACK AND FLORENCE JAMES, SET IN A SYDNEY HOTEL

Stephan Elliott is a Sydney native who has done more than most Australian writers and artists to explore the old Australian stereotype of hard-living and hard-drinking “Bruces and Sheilas” in his sublime road-comedy, The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert (1994), which Elliott wrote and directed. It is the hilarious story of a truly odd trio – two drag queens and a transgender woman – who traverse the Australian Outback, from Alice Springs in the north to Sydney in the south, in a tour-bus called “Priscilla”.

Stephan Elliott is a Sydney native who has done more than most Australian writers and artists to explore the old Australian stereotype of hard-living and hard-drinking “Bruces and Sheilas” in his sublime road-comedy, The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert (1994), which Elliott wrote and directed. It is the hilarious story of a truly odd trio – two drag queens and a transgender woman – who traverse the Australian Outback, from Alice Springs in the north to Sydney in the south, in a tour-bus called “Priscilla”.

Such has been the incredible success of Priscilla, which was turned into an almost equally successful musical (for which Elliott co-wrote the book or libretto), that it has almost completely obscured the other films that Elliott has written and directed. However, there have been some other gems, notably Easy Virtue (2008), a screen adaptation of the Noël Coward play of the same name (eighty years after Alfred Hitchcock’s silent version) and in particular Swinging Safari (2017), a coming-of-age story set in the truly “swinging” (or wife-swapping) 1970s.

KEY SYDNEY WORK: THE ADVENTURES OF PRISCILLA, QUEEN OF THE DESERT (1994)

If the surname looks familiar, that is because John Farrow is indeed Mia Farrow’s father. And yet that is arguably the least interesting thing about John Farrow, whose own life is worthy of being turned into a biopic. It is the story of a young Australian (Farrow was born in Sydney in 1904) who literally took to the high seas for adventure, where he met the great American film-maker Robert J. Flaherty (the maker of the first truly successful documentary, Nanook of the North (1922), which bore the wonderful subtitle of A Story Of Life and Love In the Actual Arctic) and, encouraged by Flaherty’s success, headed to California to become a filmmaker himself.

If the surname looks familiar, that is because John Farrow is indeed Mia Farrow’s father. And yet that is arguably the least interesting thing about John Farrow, whose own life is worthy of being turned into a biopic. It is the story of a young Australian (Farrow was born in Sydney in 1904) who literally took to the high seas for adventure, where he met the great American film-maker Robert J. Flaherty (the maker of the first truly successful documentary, Nanook of the North (1922), which bore the wonderful subtitle of A Story Of Life and Love In the Actual Arctic) and, encouraged by Flaherty’s success, headed to California to become a filmmaker himself.

Farrow first found work in Hollywood as an actor, but he soon branched out into directing, producing and writing. As a screenwriter alone, he is credited (and sometimes uncredited) with writing, co-writing or writing the “titles” (the subtitles for silent movies) more than 25 films, including an early version of A.E.W. Mason’s classic 1902 novel, The Four Feathers (1929), the Charles Laughton and Clark Gable version of Mutiny On The Bounty (1935) and, more than two decades later, Around the World in 80 Days (1956).

KEY SYDNEY WORK: THE SEA CHASE (1955), PART OF WHICH IS SET IN SYDNEY

Like Nick Enright before her, Angela Webber died tragically young; indeed, just like Enright, she died aged only 52. Although she may not have matched Enright’s prodigious output of plays, musicals and screenplays, she was still an accomplished actress and writer, whose greatest early creation was the character of a self-styled “Punk Pensioner”, Lilian Pascoe, who became a staple of Australian radio and TV, loving heavy metal music and enjoying the kind of gloriously rambunctious old age that, sadly, Webber herself never got to experience.

Like Nick Enright before her, Angela Webber died tragically young; indeed, just like Enright, she died aged only 52. Although she may not have matched Enright’s prodigious output of plays, musicals and screenplays, she was still an accomplished actress and writer, whose greatest early creation was the character of a self-styled “Punk Pensioner”, Lilian Pascoe, who became a staple of Australian radio and TV, loving heavy metal music and enjoying the kind of gloriously rambunctious old age that, sadly, Webber herself never got to experience.

As a writer, Webber’s greatest and most successful work was the children’s TV comedy, Mortified (2006-07), which she created before writing or co-writing many of its episodes. Telling the truly universal story of a 12-year-old girl, Taylor, who is so permanently “mortified” by her family, especially her parents, that she dreams of escaping the small Australian beach resort in which she lives (the magnificently named “Sunburn Beach”) and going…well, anywhere to get away from them. As the father of an 11-year-old daughter myself, who is prone to saying “Just don’t!” to whatever I say or do in public, I can personally testify to the exquisite (if agonizing) writing of Mortified, which was probably why it sold to so many other countries around the world.

KEY SYDNEY WORK: THE WEEKLY COLUMN THAT SHE WROTE FOR THE SYDNEY MORNING HERALD IN THE 1990S ABOUT “THE SHABBY FAMILY”, WHICH WAS BASED ON HER OWN FAMILY AND WHICH PROVIDED MUCH OF THE INSPIRATION AND MATERIAL FOR MORTIFIED

Andrew Bovell is a successful writer for theatre, television and film, whose credits include Who’s Afraid of the Working Class? (1998), a play he co-wrote with several other authors that is about the lives of a number of Melbourne adolescents who, like most teenagers, stay out late while their fearful parents wonder whether they will ever come home at all. It was adapted into a film called Blessed (2009), starring Frances O’Connor as one of the increasingly frantic mothers.

Andrew Bovell is a successful writer for theatre, television and film, whose credits include Who’s Afraid of the Working Class? (1998), a play he co-wrote with several other authors that is about the lives of a number of Melbourne adolescents who, like most teenagers, stay out late while their fearful parents wonder whether they will ever come home at all. It was adapted into a film called Blessed (2009), starring Frances O’Connor as one of the increasingly frantic mothers.

However, Bovell’s greatest success, both on stage and screen, was his breakthrough play, Speaking In Tongues (1996), which was a huge critical and commercial success in Australia and which he later adapted for the screen. Lantana (2001), as the film is called is both a great Sydney film (the title comes from a weed found all over the city) and one of the greatest noirs of the last two decades (even if the action often takes place in bright sunlight rather than shadows). Starting with the discovery of a woman’s shoe in a lantana bush, it spirals upwards and outwards to take in the stories of all those affected by the discovery, including the policeman investigating the woman’s disappearance, who is played by Anthony LaPaglia, in what, alongside his turn as Daphne’s brother in Frasier, is a career-best performance.

KEY SYDNEY WORK: LANTANA (2001)

David Caesar is an Australian writer-director who has worked extensively in television and film. As a director, he has worked on a remarkably wide variety of TV series, ranging from Bananas In Pyjamas (1992-2001), the fantastically successful children’s show that began in Australia before conquering the world, to Rush (2008-11), a cop show about Melbourne’s Tactical Response Unit, a kind of Australian SWAT team that responds to major incidents such as bank robberies or carjackings.

David Caesar is an Australian writer-director who has worked extensively in television and film. As a director, he has worked on a remarkably wide variety of TV series, ranging from Bananas In Pyjamas (1992-2001), the fantastically successful children’s show that began in Australia before conquering the world, to Rush (2008-11), a cop show about Melbourne’s Tactical Response Unit, a kind of Australian SWAT team that responds to major incidents such as bank robberies or carjackings.

Caesar’s film credits, as both a writer and director, are nowhere near as long or as impressive as his TV credits. Nevertheless, he has made several Australia-set movies, in particular, Idiot Box (1996), which has the memorable (and informative) tagline, “The darkly comic tale of the young and useless”; Dirty Deeds (2002), a 1960s Sydney-set crime drama in which, as in The Long Good Friday (1979), the US Mafia are depicted as trying to usurp a local crime lord; and Mullet (2001), the story of a drifter who returns home. Idiot Box and Mullet are especially noteworthy for starring a young Ben Mendelsohn, the brilliant Australian actor who finally gained global fame for his stunning performance as King George VI in Darkest Hour, during which he occasionally upstaged even the great Gary Oldman’s Churchill.

Download the script for DARKEST HOUR here for free.

KEY SYDNEY WORK: DIRTY DEEDS (2002)

Joan Long’s journey through the Australian film industry is analogous to that of Peggy Olson in Mad Men, in that she worked her way up from being a secretary to becoming a writer, director and producer. After World War Two, her typing skills were employed by the newly formed Australian National Film Board, a Government body that was explicitly set up to try and boost Australian film production, which had largely languished in the first half of the 20th century. However, she eventually proved to producer Stanley Hawes that she was capable of being much more than a typist and by the late 1960s she was overseeing a series of documentaries about early Australian film-making, The Picture That Moved: Australian Cinema 1896-1920 (1968) and The Passionate Industry: 1920-1930 (1971), as well as scripting a documentary, Paddington Lace (1970), about the Paddington district of Sydney, which had become something of an artists’ colony.

Joan Long’s journey through the Australian film industry is analogous to that of Peggy Olson in Mad Men, in that she worked her way up from being a secretary to becoming a writer, director and producer. After World War Two, her typing skills were employed by the newly formed Australian National Film Board, a Government body that was explicitly set up to try and boost Australian film production, which had largely languished in the first half of the 20th century. However, she eventually proved to producer Stanley Hawes that she was capable of being much more than a typist and by the late 1960s she was overseeing a series of documentaries about early Australian film-making, The Picture That Moved: Australian Cinema 1896-1920 (1968) and The Passionate Industry: 1920-1930 (1971), as well as scripting a documentary, Paddington Lace (1970), about the Paddington district of Sydney, which had become something of an artists’ colony.

In the 1970s, Long moved from documentaries to drama, as she wrote the screenplay for Caddie (1976), adapting Caddie: The Story of a Barmaid, which was the story of a Sydney woman in the 1920s who tries to escape from her violent and drunken husband. It was a huge domestic hit and soon led Long to adapt another 1920s-set story, that of a traveling film exhibitor, The Picture Show Man (1977). Eventually, Long completed her remarkable rise up the cinematic ranks by becoming a major Australian film producer, notably on Silver City (1984), a drama about Polish immigrants arriving in Australia after the end of World War Two.

KEY SYDNEY WORK: CADDIE (1976)

Baz Luhrmann is not only the most successful Australian film director in the last thirty years but one of the greatest film-makers from any country in the last thirty years. His “Red Curtain Trilogy” of films – Strictly Ballroom (1992), Romeo + Juliet (1996) and Moulin Rouge! (2001) – were not a traditional trilogy, in the sense of being linked stories, but they were all equally inventive, equally extraordinary explorations of the idea of performance and what it means to be a performer, or even, in the case of Romeo + Juliet, what it means to be a “tragic” hero or heroine. And Lurhmann’s co-writer on those three magnificent movies was Craig Pearce.

Baz Luhrmann is not only the most successful Australian film director in the last thirty years but one of the greatest film-makers from any country in the last thirty years. His “Red Curtain Trilogy” of films – Strictly Ballroom (1992), Romeo + Juliet (1996) and Moulin Rouge! (2001) – were not a traditional trilogy, in the sense of being linked stories, but they were all equally inventive, equally extraordinary explorations of the idea of performance and what it means to be a performer, or even, in the case of Romeo + Juliet, what it means to be a “tragic” hero or heroine. And Lurhmann’s co-writer on those three magnificent movies was Craig Pearce.

Pearce was an actor before he became a writer, appearing in an Australian soap opera, The Restless Years, and small Australian films such as To Make A Killing (1988). However, at the end of the 1980s, he and fellow actor Luhrmann (who he had met in school) co-wrote Strictly Ballroom as a play, before adapting it for the screen, from which it has become the global phenomenon that has directly or indirectly inspired such enormously successful “dance reality” shows as the BBC’s Strictly Come Dancing, which is so successful in Britain that it is universally known simply as “Strictly”.

Lurhmann and Pearce brilliantly capitalized upon the success of Strictly Ballroom by going to Hollywood and making Romeo + Juliet, which might just be the greatest Shakespeare film ever made; arguably only Peter Brook’s 1970 film of King Lear (a screen adaptation of his famous RSC stage production of a decade earlier) comes close to it for being both truly Shakespearean and truly cinematic. And they pulled off their artistic “hat-trick” with the third installment of the “Red Curtain Trilogy”, Moulin Rouge!, which virtually invented the now-common cinematic trope of using 20th or even 21st century songs in a story set before the 20th century, thus completely overturning the whole idea of what was or was not anachronistic. And if Lurhmann and Pearce’s later films, including The Great Gatsby (2013), do not quite match the majesty of the “Red Curtain Trilogy”, well, as Baz and Craig would surely point out, so very few films do.

KEY SYDNEY WORK: STRICTLY BALLROOM (1992)

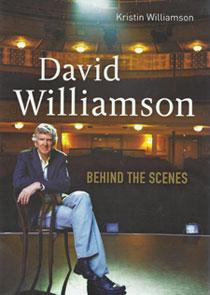

David Williamson is one of the most successful Australian playwrights and screenwriters of the late 20th century and indeed of the 21st century so far, whose output for stage and screen has been prodigious both in quantity and quality. Many of his most successful plays have been adapted by him for the screen, including The Removalists (1975), an examination of the domestic violence that was almost endemic in Australia (and indeed many other countries) at the time; Don’s Party (1976), about an election-night party that goes disastrously wrong; and Emerald City (1988), an autobiographical story about a commercially successful screenwriter who dreams of writing a great play.

David Williamson is one of the most successful Australian playwrights and screenwriters of the late 20th century and indeed of the 21st century so far, whose output for stage and screen has been prodigious both in quantity and quality. Many of his most successful plays have been adapted by him for the screen, including The Removalists (1975), an examination of the domestic violence that was almost endemic in Australia (and indeed many other countries) at the time; Don’s Party (1976), about an election-night party that goes disastrously wrong; and Emerald City (1988), an autobiographical story about a commercially successful screenwriter who dreams of writing a great play.

However, it is the screenplays that Williamson wrote for a series of hugely successful Australian films in the early 1980s that made him an internationally successful writer and not just a domestically successful writer. In particular, he wrote his own “Australian Trilogy” of films, the first two of which starred Mel Gibson, cementing Gibson’s status as a truly global star and in the process introducing the rest of the world to periods of Australian history that had hitherto been largely unknown outside the country. They were: Gallipoli (1981), Peter Weir’s war film about the disastrous Australian campaign in Turkey in World War One; The Year Of Living Dangerously (1983), which was also directed by Weir (who co-wrote the screenplay with Williamson), based on the novel of the same name by Christopher Koch that examined Western (including Australian) involvement in Indonesia in the 1960s; and finally, Phar Lap (also 1983), which was directed by Simon Wincer and told the story of the racehorse whose successes captivated Australia during the 1930s.

KEY SYDNEY WORK: EMERALD CITY (1988), WHICH IS SET IN SYDNEY

Martin Keady is an award-winning scriptwriter whose work has been produced for film, television, stage and radio. His major credits include: The Final, a short film about the famous ending of the 1979 FA Cup Final, which was shown on Channel Four; Moon the Loon, a play about the legendary Who drummer, Keith Moon, which was premiered at The Edinburgh Festival; and a collection of love poetry, Shards, extracts from which have been broadcast on Radio Four.” http://theshakespeareplays.com/

Martin Keady is an award-winning scriptwriter whose work has been produced for film, television, stage and radio. His major credits include: The Final, a short film about the famous ending of the 1979 FA Cup Final, which was shown on Channel Four; Moon the Loon, a play about the legendary Who drummer, Keith Moon, which was premiered at The Edinburgh Festival; and a collection of love poetry, Shards, extracts from which have been broadcast on Radio Four.” http://theshakespeareplays.com/

For all the latest from The Script Lab, be sure to follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.