By Andrew Schwartz · March 18, 2019

When Academy Award-winning editor and sound designer Walter Murch concedes in his book In The Blink of an Eye that the process of editing film can be reduced to a single idiom – “cutting out the bad bits” – he does so with a sense of irony. To many, editing is merely the cutting of bad bits from a film to leave room for the otherwise good bits. But as anyone who’s been even remotely involved in film production can attest to, there’s so much more to editing than meets the eye. To an outsider, just how much work goes into distracting them from the fact they witnessed a cut can be baffling.

The fundamental question Murch therefore posits is what makes a good cut? For screenwriters, this question can be interchangeable with what does the audience need to see? And, as one scene flows into the next, how will this make them feel?

Whereas a scene must generally satisfy two distinct criteria – advancing the story and/or revealing something about a character – an edit, according to Murch, must satisfy six fundamental requirements to serve the ultimate question of how will this make the audience feel? Each of the six criteria is assigned its own (slightly tongue-in-cheek) intrinsic value relative to the development of the overall film. Here’s how Murch introduces the Rule of Six in his book along with their respective values and purpose:

1) it is true to the emotion (51%) of the moment;

2) it advances the story (23%);

3) it occurs at a moment that is rhythmically (10%) interesting and ‘right’;

4) it acknowledges what you might call ‘eye-trace’ (7%) – the concern with the location and movement of the audiences focus of interest within the frame;

5) it represents ‘planarity’ – the grammar of three dimensions transposed by photography to two dimensions (5%);

6) and it respects the three-dimensional continuity (4%) of the actual space.”

The biggest thing to note about the Rule of Six is the emphasis put on the top three rules; most notably on emotion. As Murch puts it, “what [the audience] finally remembers is not the editing, not the camerawork, not the performances, not even the story – it’s how they felt.” Emotion is the singularity in all stories; our emotional connection to archetypical characters is the reason certain stories have been told for thousands of years. Murch’s Rule of Six demonstrates how even with an aspect of filmmaking as technical as editing, homing in on the emotional through-line is paramount.

Is there a logical cause and effect? Will the audience stay emotionally engaged through each scene? As Scott Meyers of Go Into the Story says, “…the first three [rules] are tightly interlocked and… utterly on point for our task as screenwriters, and instructive to note how emotion ranks first in Murch’s list. That puts his film editing POV squarely in the arena of the story’s characters.”

Even in the most extreme examples of cinema, the emotional through-line is never lost. Murch explains this in the following way, “… if the emotion is right and the story is advanced in a unique and interesting way, in the right rhythm, the audience will tend to be unaware of (or unconcerned about) editorial…”

Taking off where films like Apocalypse Now (edited by Murch) left off, Dunkirk pushes the envelope of filmmaking convention in many ways, but most notably in the execution of multiple storylines. With a script that sits at around 82 pages, the film relies heavily on visual action to tell the story. Never losing sight of emotion, story and rhythm as one storyline transitions into the next, Nolan and Smith bring to life an epic story told on a grand scale.

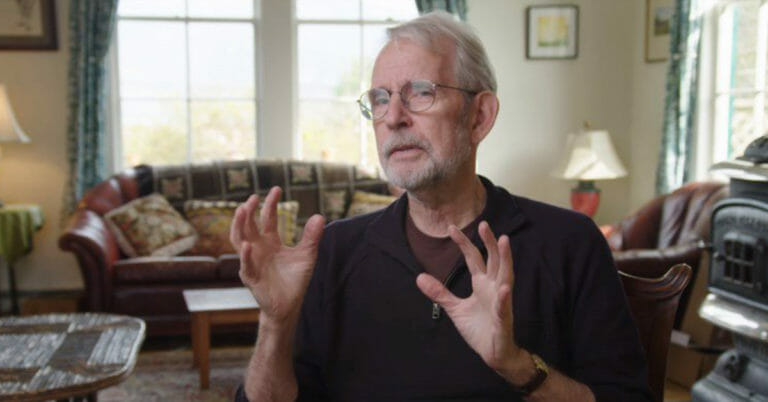

Nolan does an excellent job of summarizing the principles of Murch’s Rule of Six at a Dunkirk Q+A hosted by the Film Society of Lincoln Center. Nolan says, “you can create empathy for character just by virtue of the physical situation.” The non-linear and often jarring storyline of Dunkirk is held together through rhythmic cuts seen through the eyes of characters central to each timeline (land, air, and sea).

In a video titled “DUNKIRK: Editing the Suspense Snowball” from the popular YouTube series This Guy Edits, Nolan and Smith’s “rising suspense” technique is examined through the ways in which multiple timelines are stitched together to give off the illusion of parallel action. One of the sequences examined in the video is the final dog fight scene: “Two different events at different locations at different times, but it feels like it’s the same beat,” Sven, the video’s creator says of the sequence. “Christopher Nolan and Lee Smith are using parallel action to heighten emotions. The meaning, the contrast and most importantly, the emotion comes down to point of view,” Sven continues. Because we see different events play out concurrently through the eyes of the central characters, we remain emotionally invested despite not being grounded in the linear progression of events.

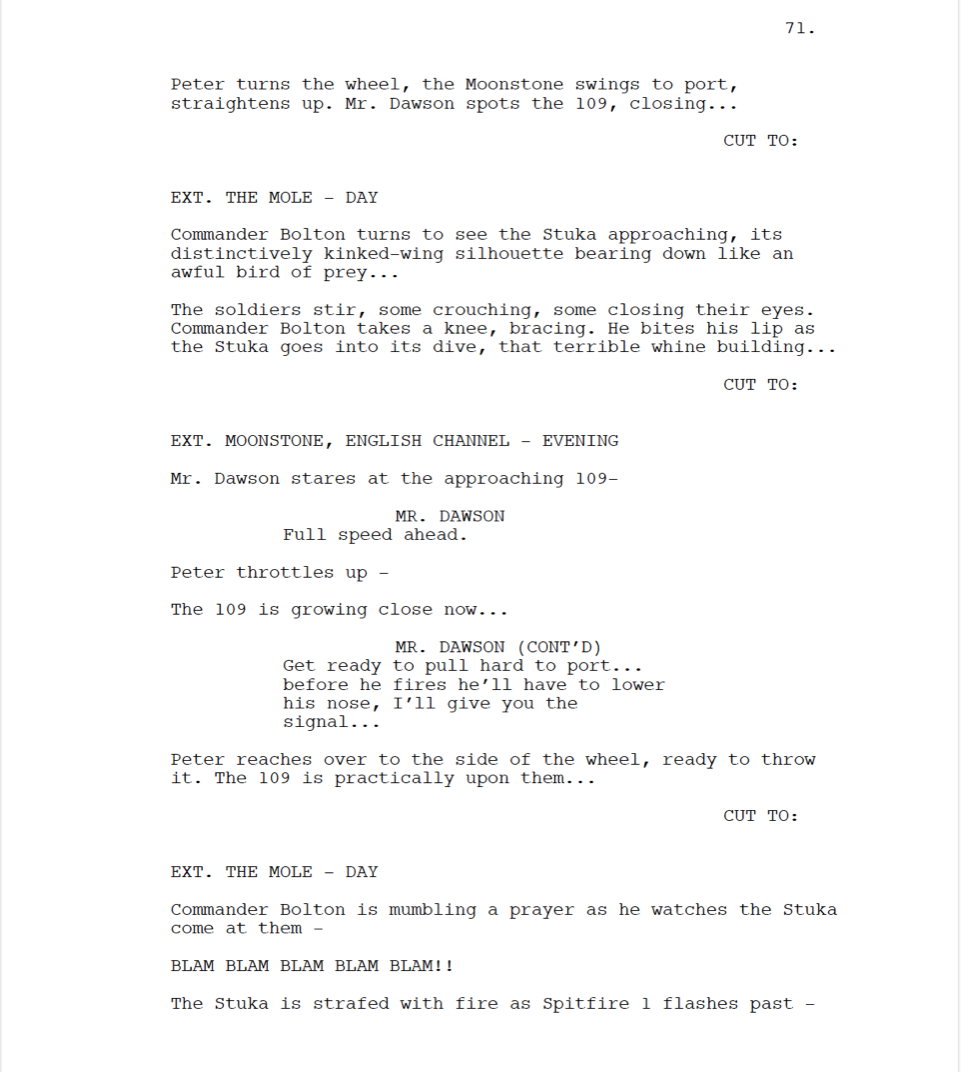

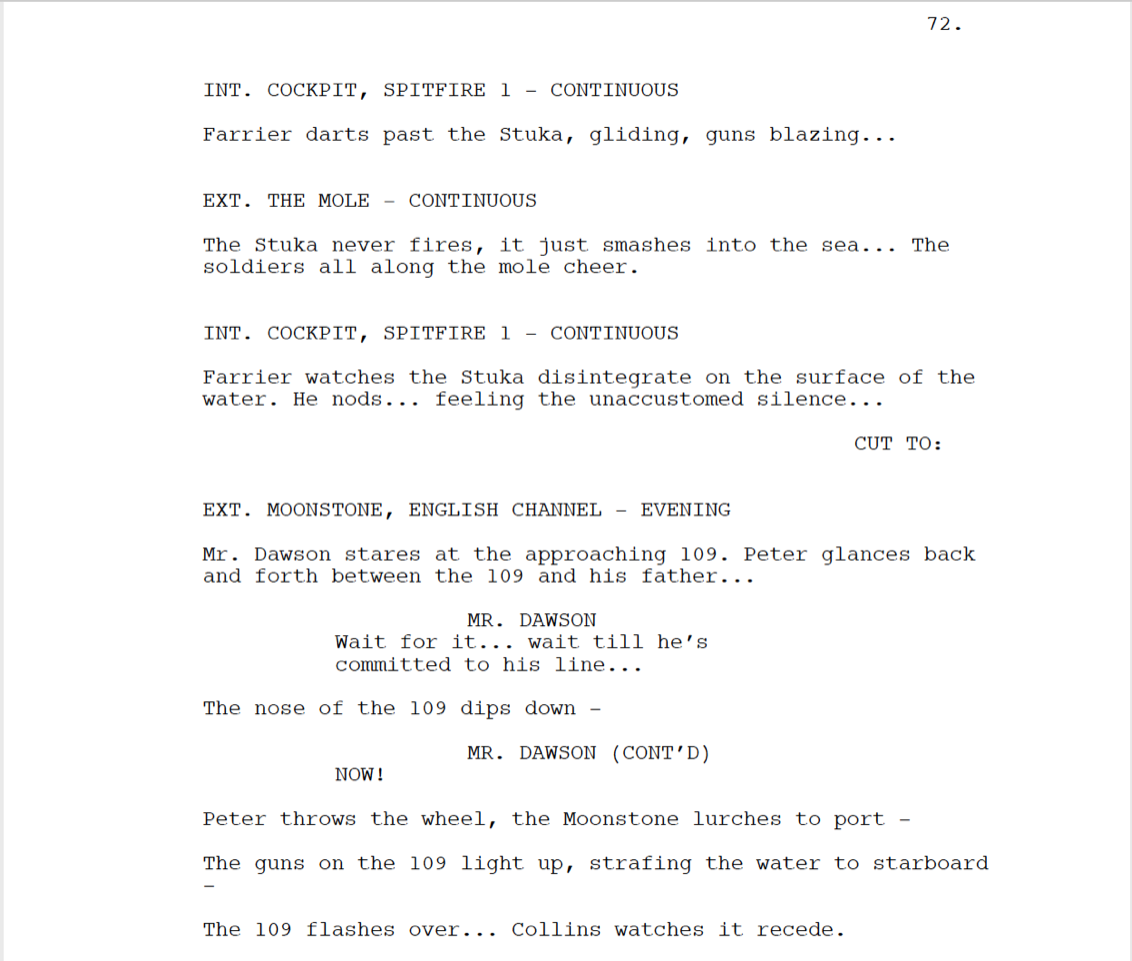

Here’s how the sequence was written for the screen:

Take note of keywords and phrases such as “whine building, guns blazing…” all written right before the scene cuts to another storyline, which play into the heightened sense of suspense. What’s also key to note here is how POV is maintained throughout each event: “[Commander Bolton] bites his lip as the Stuka goes into its dive, that terrible whine building…” Emotion, story, and rhythm are perfectly combined to execute a sequence that ends in a triumphant and emotionally engaging moment: Victory.

What’s most important is to prioritize the list so that topper most aren’t sacrificed for the secondary items. Every production starts with a script, and every good script begins with an empathetic protagonist. As the protagonist actively moves from one scene to the next while satisfying the overall thematic and structural arc of the film, emotion, story and rhythm are key factors to keep in the forefront of our minds. In doing so, the audience will remain emotionally invested throughout the story and even after the film ends. As Murch concludes,

“That brings me back to one of the central responsibilities of the editor, which is to establish an interesting, coherent rhythm of emotion and though – on the tiniest and the largest scales – that allows the audience to give themselves to the film… a good film that is well-edited seems like an exciting extension and elaboration of the audience’s own feelings and thoughts…”

Swap “editor” with “screenwriter” and the message is the same: write only what the audience should see, which will, in turn, make them feel what you want them to.

Photo Credit: asoundeffect.com and Academy Originals

For all the latest from The Script Lab, be sure to follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.