By V. Prasad · June 15, 2011

If you’ve ever found yourself on the edge of your seat at the end of a football game, you’d know that a screenwriter can learn a lot from sports. A great ball game (football, basketball or otherwise) can teach you important lessons about suspense and holding an audience’s interest.

Sports use the same dramatic principles as screenwriting. There’s a protagonist (the team you’re rooting for) and an antagonist (the team they’re playing against). And your team has a crystal clear goal: score more points than the other team before the game is over.

If the game is close in the final minutes, you’re captivated by the hope your team will win and the fear that they will lose, because you know exactly what your team needs to do to win and how much time they have to do it.

In football, to score a touchdown, you have to get the tip of the ball across the plane of the goal line. Do that and your team gets six points. If you’re even a millimeter short, you get nothing.

That’s the kind of goal you want to define for you main character: One where they get it all or they get nothing. The line between success and failure should be clear and unmistakable.

The briefcase full of cash. The secret war plans. The Maltese Falcon. Sometimes, the goal is the least interesting aspect of the story. Alfred Hitchcock coined the term “MacGuffin” to describe the thing his characters were trying to attain. To Hitchcock, the “MacGuffin” itself was unimportant as long as it was specific and that the audience understood what was at stake if the main character didn’t get it.

If you’re not writing an action movie or a thriller, you probably won’t have a MacGuffin. But, you should still find a discrete goal for your main character, one where success or failure is complete. Where there’s no middle ground.

Make sure to phrase your goal as an achievement. Stay away from using the words “to be” or “to become.” “To become a dancer” is not a clear goal. “Getting into the Royal Ballet Academy” or “Winning the ‘So You Think You Can Dance’ Competition” work better because they give the character something specific to work towards and, at the climax of the movie, the audience will know definitively whether they succeeded or failed.

Now, what if you’re doing a “character-driven” movie? One where the story centers on what the character unconsciously needs as opposed to what they consciously want? That unconscious need will still manifest itself in tangible goals.

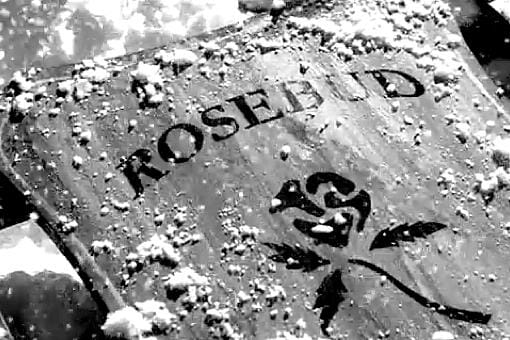

In Citizen Kane, throughout the story, Kane tries to build a newspaper empire, run for public office, and turn his mistress into an opera star. Each of these goals is clear in itself and they are all guided by Kane’s unconscious need, which is enigmatically hinted at in his dying word: “Rosebud.”

So next time you find yourself drawn into an exciting game, pay attention to the short and long term goals and how they keep you, the viewer, on the edge of your seat.