By Martin Keady · January 30, 2020

In our age of screen ubiquity, in which screens (large, small or mobile phone-sized) are seemingly everywhere and apparently showing every film and TV series that has ever been made, it is genuinely strange that one of the greatest television series ever written, Our Friends In The North (1996), is not as widely or easily available as it should be. It has had neither the major repeat viewing within Britain nor the wider international distribution that its extraordinary, indeed almost Shakespearean, quality deserves. Supposedly, this is because of a series of long-running (and ultimately very dull) disputes over “rights”, including the rights to some of the music used in the series.

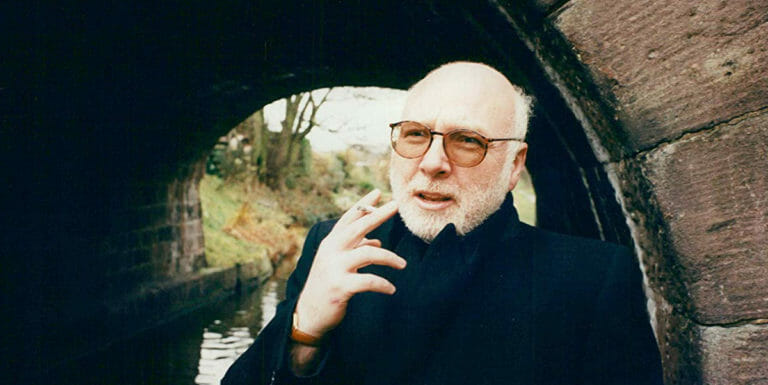

Nevertheless, even if it has to be viewed on YouTube, Our Friends In The North absolutely demands to be seen, as it is one of the few examples of a TV series that can be genuinely said to tell the history (or at least a large part of it) of the country in which it was made. In that respect, Our Friends In The North is fully deserving of its reputation as Britain’s Heimat and its creator, Peter Flannery, is undoubtedly one of the great poet laureates of television.

Peter Flannery is a native of England’s north-east, a relatively impoverished and largely post-industrial part of Britain that is sometimes crudely dismissed as “Geordieland” (the term “Geordie” being a nickname for the inhabitants of Newcastle, the region’s biggest city). Indeed, Flannery was actually born, in 1951, in Jarrow, the historic town that was the starting point for the fabled “Jarrow March” against widespread unemployment in the truly impoverished 1930s. Nevertheless, the north-east of England has also been the home to some of Britain’s greatest television writers, notably the comedy writing duo of Ian La Frenais and Dick Clement. As the rapper Daddy G, a key member of the great British band Massive Attack, famously said of his own hometown of Bristol, “The best times happen in the worst areas”. In the same vein, some of the richest and most satisfying stories come from some of the poorest and most economically disadvantaged areas, and so it is with Flannery’s epic tale of his own homeland.

Our Friends In The North actually began as a stage play before it was adapted by Flannery himself for television. After graduating from the University of Manchester in the early 1970s, which was a particularly difficult period for the entire north of England, including the north-east, as immortalized in La Frenais and Clement’s supreme Britcom Whatever Happened To The Likely Lads? (1973-74), he found himself at the end of the decade in the very different environs of William Shakespeare’s home town of Stratford Upon Avon, where he became the resident playwright of the Royal Shakespeare Company. Flannery wrote several original stage plays while he was in Stratford, but it was one in particular, Our Friends In The North, which was first produced by the RSC in 1982, that both made his name and established his credentials as a playwright worthy of comparison to the great Bard of Avon himself.

To be favorably compared with Shakespeare is the ultimate accolade for any dramatist in any medium, as the term “Shakespearean” is, among many other things, short-hand for a work of genuinely epic scale, depth and historical perspective – a true “state of the world”, usually including a “state of the nation”, address. In the case of Flannery, it is more applicable than with most other writers, because, as he has readily admitted himself, he was directly inspired by Shakespeare and his plays. It was while watching dress rehearsals of the RSC’s Henry IV Parts I and 2 that Flannery was encouraged to “up his game” and write a play that ranged over great swathes of time and space, in the way that so many of Shakespeare’s greatest plays did. And so he came up with Our Friends In The North, and he must have been tickled, to say the least, when so many reviewers of the original play wondered aloud whether the title was a Shakespearean quotation, a mistake made a decade and a half later by some of the first reviewers of the subsequent TV series.

Our Friends In The North, the play, was the basis for the later TV series of the same name, but there were some crucial differences, in particular, the inclusion of many scenes set in Rhodesia, the former British colony that is now Zimbabwe. For the TV series, that “international” dimension was dropped and instead there was a scrupulous focus on the national dimension, which effectively told the story of post-war Britain from the 1960s to the 1990s.

The original stage version provided the superstructure of the later TV series, in its juxtaposition of a close-knit group of friends from Newcastle (three men – Nicky, “Tosker” and “Geordie” – and one woman, Mary, who becomes the object of desire for at least two of the men) and the much broader backdrop of Britain’s post-imperial history. Flannery’s genius was to come up with an ingenious, overarching structure in which each part of the story (and subsequently, each episode of the series) took place in the same year as a British general election. Consequently, Our Friends In The North began in 1964 with the election of Harold Wilson (amid his promises that Britain would be reborn in the “white heat” of new technology) and ended in 1996, a year before the election of Tony Blair’s “New Labour”. Indeed, such was the success of the TV series that it was even considered by some commentators to have contributed to the electoral success of New Labour a year later. In both instances, at the beginning and the end of the story, a new left-wing Government ostensibly ushered in a new era of potential growth, both personal and national, after the long-played-out end of a failing right-wing regime.

However, like any précis of a great work of drama, this broad summation of Our Friends In The North does not convey the ambition, the complexity and the sheer impact of the play and in particular the TV series. Our Friends In The North finally came to television in the mid-1990s (after more than a decade in Britain’s own version of “development hell”), and when it did the story was updated by Flannery to take in the 15 years that had passed since he had first written the play. Like Edgar Reitz’s Heimat, the even more ambitious story of Germany in the 20th century, Our Friends In The North simultaneously focused on both the micro (the unrealistic ambitions and petty jealousies of a group of individuals who were superficially very similar but in reality completely different) and the macro (including huge national themes of civic, state and police corruption).

Our Friends In The North was a truly star-making series. It not only established Flannery himself as Britain’s pre-eminent television dramatist (having already established himself as one of its great contemporary stage dramatists) but its cast, especially the core four of Christopher Eccleston, Mark Strong, Daniel Craig (yep, the best Bond since Connery began here) and Gina McKee, all became screen stars (in both television and film) as a result. Of course, that only makes it all the more perplexing that the BBC has neither launched a full-scale repeat (the series has occasionally been repeated, but not on the corporation’s main channels) nor trumpeted the series internationally in the way that it should have done.

Fortunately, the fraught after-life of Our Friends In The North has not completely occluded its original astonishing impact in Britain, both on television itself and more broadly, even in the realm of politics. In the authentically stunning ending of the series, Flannery combined both tragedy and comedy in a way that even Shakespeare himself (the greatest tragicomedian of all time) would have approved of. For me, and for many of my generation, that ending was as much a part of growing up in mid-nineties Britain as the music of Oasis (which soundtracked it) and the eventual election of Tony Blair and New Labour. And if, ultimately, all that promise – both of Oasis and New Labour – was not completely fulfilled (and there are many who would say that in both instances it was not remotely fulfilled), then, as Flannery himself would have noted, that is as much a part of life as the initial, exhilarating promise of youth.

Martin Keady is an award-winning scriptwriter whose work has been produced for film, television, stage and radio. His major credits include The Final, a short film about the famous ending of the 1979 FA Cup Final, which was shown on Channel Four; Moon the Loon, a play about the legendary Who drummer, Keith Moon, which was premiered at The Edinburgh Festival; and a collection of love poetry, Shards, extracts from which have been broadcast on Radio Four.” http://theshakespeareplays.com/

Martin Keady is an award-winning scriptwriter whose work has been produced for film, television, stage and radio. His major credits include The Final, a short film about the famous ending of the 1979 FA Cup Final, which was shown on Channel Four; Moon the Loon, a play about the legendary Who drummer, Keith Moon, which was premiered at The Edinburgh Festival; and a collection of love poetry, Shards, extracts from which have been broadcast on Radio Four.” http://theshakespeareplays.com/

For all the latest from The Script Lab, be sure to follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.