By Ken Miyamoto · January 20, 2020

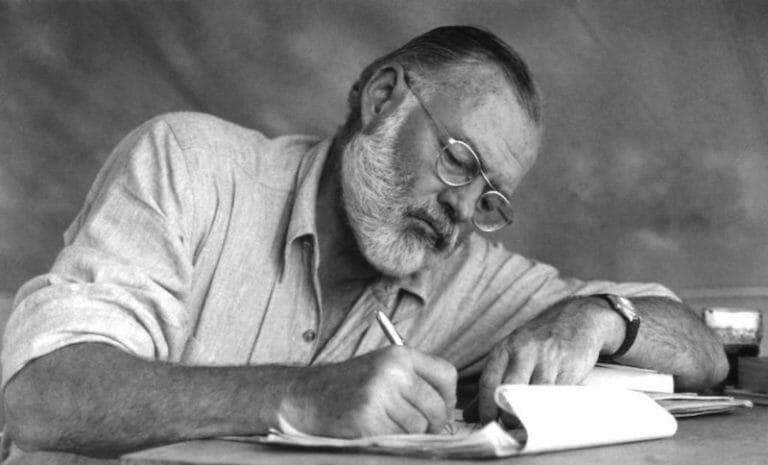

What are some inspiring writing lessons that writers can learn from Ernest Hemingway and his own writing journey?

Welcome to the inaugural post of our new ongoing series, Inspiring Writing Lessons from the Greats, where we feature inspiring stories from some of the greatest writers and filmmakers of our time and apply the lessons that can be learned from them to your screenwriting journey.

Here we feature the story of Ernest Hemingway, his lost manuscripts, and how he turned a nightmare situation into an amazing career…

It was the first week of December 1922. Ernest Hemingway was just a 23-year-old writer making ends meet as a journalist for the Toronto Daily Star. He was on assignment in Lausanne, Switzerland covering the Geneva Peace Conference. His wife of just one year at the time, Elizabeth Hadley Richardson, was back in Paris nursing a cold.

Hemingway missed her and suggested that she join him in Lausanne. As she packed for the trip, she decided to bring all of Hemingway’s works in progress with her. Hemingway had just met successful journalist and author Lincoln Steffens. Perhaps Hemingway could share the work with Steffens and continue writing during his time on assignment.

She packed all of his manuscripts into an overnight suitcase. Her horrible mistake was including the carbon copies of each manuscript — original carbon copies that worked as insurance for any possible lost drafts.

These were early Nick Adams stories about Michigan, the short stories Hemingway had been working on for many months.

She boarded her train, settled into her seat, and stowed her bags. She went to buy water before the train left the station. When she returned, the small overnight suitcase was gone.

Distraught, she worked with the conductor to search the train for the suitcase. Nothing.

She cried the whole eight-hour train ride.

When she arrived, Hemingway found her in tears — with no clue as to what could be causing such an emotional breakdown. Then she told him what had happened.

Ernest wrote in A Moveable Feast:

“I had never seen anyone hurt by a thing other than death or unbearable suffering except Hadley when she told me about the things being gone. She had cried and cried and could not tell me. I told her that no matter what the dreadful thing was that had happened nothing could be that bad, and whatever it was, it was all right and not to worry. We could work it out. Then, finally, she told me. I was sure she could not have brought the carbons too and I hired someone to cover for me on my newspaper job. I was making good money then at journalism and took the train for Paris. It was true alright, and I remember what I did in the night after I let myself into the flat and found it was true.”

It is unclear what had happened in the flat. Regardless, his work was gone.

It’s important to remember that at this time in his life, Hemingway was not the writer he would soon become.

None of his work had been published yet. All that was left in Paris was two short stories — Up in Michigan, which Gertrude Stein had called unpublishable, and My Old Man, which an editor had at the time.

Everything else was gone.

“It was a bad time, and I did not think I could write any more then,” Hemingway wrote.

Despite losing all of his work, Hemingway continued on. This tragic turn of events could have derailed Hemingway’s drive to write. He was making good money as a journalist. He wasn’t getting any of his stories published. And he just had the universe seemingly tell him that maybe he should consider another line of work other than writing books and short stories.

Instead of relenting to an unfortunate turn of events, Hemingway changed his writing style to make up for time constraints by writing shorter sentences, cleaner paragraphs, and more readable prose. This allowed him to write faster.

Just four years later, he would publish the bestseller The Sun Also Rises. And the rest is literary history.

All writers struggle — even the most iconic masters. You can choose to succumb to the struggle and use any number of excuses to quit or you can persevere as Hemingway did.

It also teaches writers how to adapt their process and style to whatever the circumstance calls for. Without that decision to shift his style to shorter sentences, cleaner paragraphs, and more readable prose, we wouldn’t have the Hemingway we know today. Everything happens for a reason.

Instead of assuming that the adversity you face is a message from the universe that you’re not meant to achieve or pursue this writing dream, consider any adversity as a message trying to tell you that you need to shift your approach.

For some writers, you may need to discover that your story isn’t meant for the screen. Perhaps it should be a novel first? For others, maybe your novel is something that would make for an outstanding limited or network series?

Listen to the whispers and signs. Not with a negative and cynical filter, but with a positive one that is leading you in the direction you need to take.

For all the latest from The Script Lab, be sure to follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

And become a member of TSL 360 to enjoy the LARGEST screenwriting education content library, featuring masterclasses, deep-dive interviews, and lectures from Academy Award-winning screenwriters, TV show-runners, producers, literary managers, agents, studio executives, and leading educators – all in one place.