By Martin Keady · November 3, 2020

David Williamson is arguably the greatest Australian screenwriter ever. He has written the full gamut of movies, from small, personal, fiercely independent films in the 1970s to internationally successful hits in the 1980s and beyond, in the process helping introduce Australia’s greatest ever movie star, Mel Gibson, to the wider world. In addition, he has also been a commercially successful and critically acclaimed playwright, whose plays have often focused on the dark underside of supposedly sunny Australia. His is almost the dream screenwriter’s career, achieving artistic greatness (and box office success) on the screen, while always continuing to pursue the non-screenwriting career that William Goldman for one thought was essential to keep a screenwriter sane.

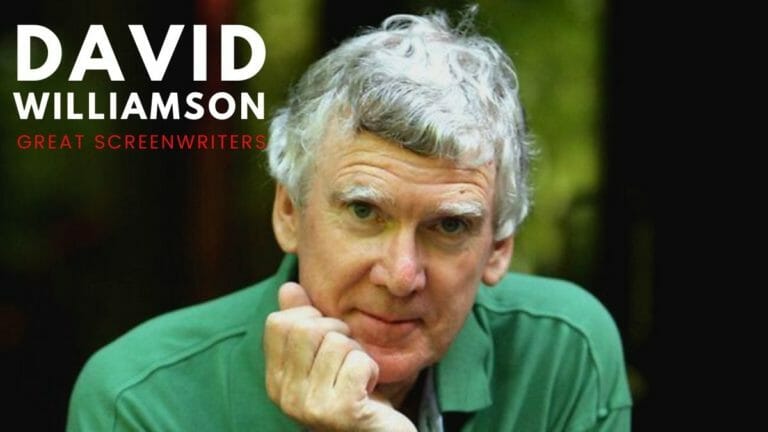

Here’s everything you need to know about one of the best living screenwriters, David Williamson.

For someone who became such a successful writer, it is fascinating to consider that Williamson’s upbringing and early career were almost as far removed from writing as possible. He was born in Melbourne, Australia in 1942, and initially, his academic focus wasn’t on literature or drama but engineering. He graduated from Monash University in Melbourne in 1965 with a degree in mechanical engineering. However, even while he was a student he was developing an interest in both writing and performing, which included writing and performing in scenes or “skits” for the “Engineers Review” and other student productions and companies.

When Williamson became a screenwriter, he used his engineering background to apply structure to his screenwriting., Screenwriting — as we are often told by Goldman and others — is ultimately about structure.

Williamson began writing full-length plays in the late 1960s. His debut play was the marvelously named The Indecent Exposure of Anthony East (1968). Rather than being, as the title perhaps suggests, the tale of a flasher, it was instead a drama about the dual life of a middle-aged Australian man, a corporate “suit” who has a side-line in writing romantic fiction.

This theme of duality, and in particular the conflict between what we want to do (especially artistically) and what we are compelled to do (to make a living), would be explored by Williamson repeatedly throughout his subsequent career. However, given that he was effectively leading a triple life himself – as a teacher (of engineering), a student (of psychology), and a writer (of drama) – the demands of leading a dual life must not have appeared as oppressive to him as they do to most people.

Williamson continued to write plays for various Melbourne theatre companies, especially the Emerald Hill Theatre Company, in the late 1960s and early 1970s. His notable plays in this period include The Removalists (1971), which was a stark account of the domestic violence that plagued Australia and other Western countries at the time (and, of course, to a large extent still does), and Don’s Party (also 1971), the party in question being an election night party, initially to celebrate an expected electoral success and then to drown the sorrows when that success does not come.

However, arguably his most important play of the early 1970s, principally because it was soon adapted into a film that Williamson wrote the screenplay for, was The Coming of Stork (also 1971, which was clearly a particularly busy year for Williamson), which was filmed in the same year as Stork.

In both the original play and the film, Williamson clearly and powerfully drew upon the world that he was most familiar with, namely academic (or college) Australian life. Williamson reveled in the ambitions and apparent contradictions of this world, with his “Stork” being a freakishly tall young man who, after losing his job because of an ill-advised striptease at work, becomes a student, which brings him into conflict with his more obviously academic and diligent class and housemates.

The film of Stork was even more successful than the original play. Indeed, it’s often credited as being the first of the Australian “new wave” of films and film-makers that would soon crash around the world in the 1970s, bringing such brilliant directors as Peter Weir and in particular his stunning 1975 feature, Picnic At Hanging Rock, to the forefront of global cinema. However, for Williamson himself it was even more important, as it established the template that would sustain him for much of the next decade, namely writing a play, seeing it performed, and then adapting it for the screen.

Stork was followed throughout the 1970s by such powerful stage/screen dramas as the films of The Removalists and Don’s Party, and then The Department, which, as the name suggests, was another university-set drama that was actually adapted for television, rather than cinema, in 1980.

By 1980, Williamson was a full-time writer who’d written numerous plays and screenplays. He’d also won numerous prestigious Australian awards for both theatre and cinema. However, he was still a big fish in a relatively small pond (or, perhaps more accurately, a whale in a fishbowl), as none of his works for stage or screen had really broken through internationally. But that changed with the series of films that he wrote at the start of the 1980s, three of which would form his own “Australia Trilogy”, telling stories from Australia’s history (rather than from Williamson’s own personal life and experience) that would captivate a wider world that had largely been unaware of them before.

The first of these quintessentially Australian but none the less universal films was Gallipoli (1981). This film tells the story of the disastrous First World War campaign in Turkey in which thousands of soldiers from Australia and New Zealand perished. It had been overseen by a young Winston Churchill and, as Darkest Hour reminded the world, it was what Churchill was most famous for before becoming Britain’s wartime leader in the Second World War and redeeming his reputation.

Gallipoli brought together three stellar Australian talents from different fields: Williamson himself, who wrote the screenplay; Peter Weir, the director, who evoked memories of his earlier masterpiece, Picnic at Hanging Rock, especially in showing the build-up to the First World War in a beautiful, lyrical, almost prelapsarian Australia; and actor Mel Gibson, who had already found fame in the first Mad Max film but cemented his acting credentials in Gallipoli. Together, the epic script, sensitive direction, and superb acting (by the whole cast and not just Gibson) catapulted the film into the global consciousness, showing the rest of the world exactly why the Gallipoli campaign is now almost universally regarded in Australia as its “loss of innocence” or “coming of age”, the specific point at which it began to slough off its traditional dependence on Britain and acquire a new and very distinctive identity of its own.

The same “dream team” (or at least “dream trio”) of Williamson, Weir, and Gibson reunited shortly afterward for another film about a challenging period in Australia’s history. That film was The Year Of Living Dangerously (1983) and the period in question was the summer and autumn of 1965, when Western journalists, including Gibson’s Australian reporter, had gathered in the Indonesian capital of Jakarta to report on the growing tensions there. This would culminate in an attempted coup by the Indonesian Communist Party. Set at a time when the Vietnam War was just beginning to be reported widely on Western TV screens, The Year Of Living Dangerously was a fascinating examination of Western and specifically Australian involvement in Asia, with all the disastrous consequences that would later consume Vietnam and much of south-east Asia.

Williamson’s screenplay for The Year Of Living Dangerously, which was based on the original 1978 novel of the same name by Cristopher Koch, was almost the polar opposite of his screenplay for Gallipoli, which was an original screenplay based on a story by Peter Weir. Where Gallipoli was essentially a tragedy, a lament for Australia’s lost youth and young men, The Year Of Living Dangerously was an avowedly unheroic story about the perils of unintended consequences, especially the unintended consequences that arose when Australia forgot its own colonial past and instead joined America, Britain, France, and others in meddling in Asia. Between them, the two films (and screenplays) can almost be regarded as depicting the two poles of 20th century Australian history: the fatal but glorious failure of Gallipoli; and the still contentious events in Indonesia half a century later.

The third of Williamson’s loosely-linked trio of Australian “period dramas” was Phar Lap (also 1983). It was the only one of the three to be set exclusively in Australia, as it told the story of a remarkable and successful racehorse that captured the hearts and even the minds of Australians in the post-Wall Street Crash period of the early 1930s. Where Gallipoli was tragic and The Year Of Living Dangerously scabrous (and occasionally even satirical), Phar Lap was obviously sentimental, even elegiac. Nevertheless, despite its subject matter, which was very different to that of the two previous films that Williamson had written, it was still intensely interested in Australia and in particular the stories and myths that had helped to create and sustain it as a nation – even those that involved such unlikely dramatic leads as a champion racehorse.

The commercial and critical success of Phar Lap, coming so soon after the similar success of Gallipoli and The Year of Living Dangerously, seems, in retrospect, to have marked the end of a chapter for Williamson. Despite gaining numerous awards, particularly in Australia, for his screenwriting for these three obviously cinematic tales, he seemed to turn his back on the supposedly glamorous life of a globally successful screenwriter that was suddenly open to him. He certainly never followed Weir and Gibson to Hollywood, instead preferring to remain in Australia and recalibrating his writing, such that he returned to the more intimate and domestic dramas that had first made his name in the 1970s.

Williamson has continued to write both plays and screenplays since his major successes in the 80s. He’s also written several plays that he then adapted for the screen. Nevertheless, as a screenwriter, the “Australia Trilogy” will stand as his lasting legacy to Australian and world cinema, an example of the kind of spectacular run of commercial and critical success that all too few screenwriters anywhere in the world have ever enjoyed. Even today, nearly forty years after they first appeared, they remain some of the most successful Australian films ever made and still demand inclusion in any discussion of the greatest works of Australian and even world screenwriting.