Sign up for the

TSL Newsletter

and get $50 off Final Draft 12

By Richard Walter · April 27, 2015

A reporter quizzed me about the different skills required for writing animation rather than live action movies.

I said there are no differences.

He opined, however, that since animated films were designed for children, there had to be differences regarding, for example, the sorts of violence that could be depicted in one compared to the other.

I told him that there are only two genres. They are not 1) animation and 2) live action; they are not 1) children’s movies and 2) grownups’ movies.

They are 1) good movies and 2) bad movies.

One screenwriting pundit claims that there are sixteen or eighteen, or two dozen, or thirty genres, I forget precisely how many, and that each one has separate, distinct rules. Fortunately for writers everywhere, the rules are described in DVDs this fellow has produced that are – surprise! – available for purchase via his website.

When my children were young our family would go away for a week during the summer to Bruin Woods, UCLA’s family camp in the San Gabriel mountains. Throughout the week there were activities for kids and grownups. In keeping with this, on movie night there were two offerings: one for youngsters, another for oldsters.

Mom and our teen daughter would go off to the grownups' film, while I would take our young son to the childrens' screening, expecting to settle him in and then, once the movie got started, planning to move over to the room screening the grownups’ film.

Instead, however, invariably I ended up staying through the whole so-called kids' picture. I did this not in order to tend to my child, who was promptly caught up in whatever was showing and probably didn’t even know I was there, but because I was caught up in it myself.

It might be some Disney lost dog movie. It might be Toy Story. Whatever it was, it was just a good movie. It had characters worth caring about. It had dialogue worth listening to all for itself because it was peppy and punchy and provocative. But the dialogue was not there all for itself. At the same time as it charmed the ear, simultaneously it delivered story and character freight.

That sounds like two achievements, but it’s really only one. How else does one advance story other than to expand character? How does one advance character other than to expand story?

But what about animation and childrens' films? Don’t kids’ movies have to soft-peddle violence?

They do not. Childrens' narratives have always been not only Grimm, but grim.

Hansel and Gretel risk being roasted and eaten by a wicked old witch. Bambi’s mom is shot; the darling faun nearly loses his young life in a forest fire. Cinderella is tormented by a cruel stepmother and sadistic stepsisters. In kiddy narratives giants and goblins and trolls harass and oppress youthful characters perpetually.

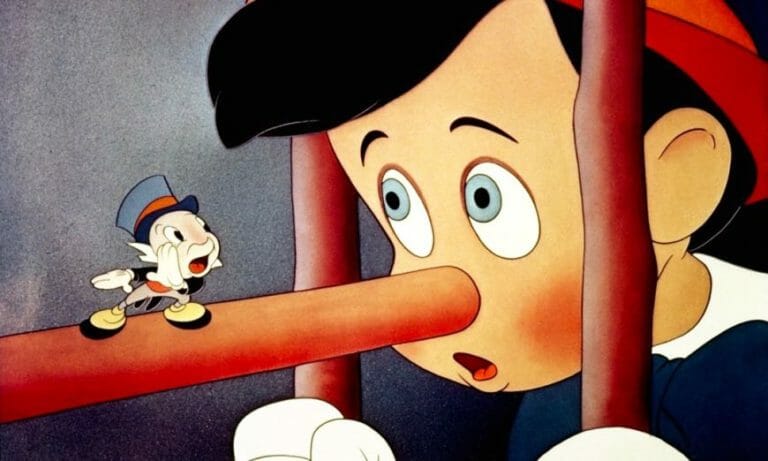

The scariest movie ever? For me it’s the Disney animated feature Pinocchio, which I saw in its original release, when I was but a wee lad, maybe four years old, probably in the late 1940s growing up in Queens.

Above the desk in my writing studio I have a framed frame, an original cel from a Pinocchio pencil test. A pencil test was a hand drawn series of cels designed to test out a particular on-screen motion.

The cel in my writing room is from a sequence in which Pinocchio swims underwater. It’s got to be from the sequence where he is captured by the whale. Is its name Monstro?

My wife bought me the Pinocchio-swimming cel because 1) I’m an addictive, obsessive, compulsive swimmer who, over thirty five years at UCLA’s incomparable Sunset Canyon Recreation Center, has swum literally ten thousand miles, and 2) because Pinocchio is my all-time favorite movie.

Pinocchio’s scariest scene is not the business involving the whale, but the scene where Pinocchio is exiled to Donkey Island, where his ability to talk is replaced by the ability merely to bray. As he tries to speak, he strangles on his own tongue. He is capable of producing only grotesque choking sounds.

From that scene I have endured nightmares my whole life.

That’s Pinocchio.

And that’s no lie.

Richard Walter teaches screenwriting at UCLA. For information regarding his summer on-campus screenwriting seminar, available to non-UCLA students, visit www.richardwalter.com.

Richard Walter Copyright © 2015