By Martin Keady · November 23, 2016

Jean-Claude Carrière is probably the greatest European screenwriter who, more than five decades into his film-writing career, continues to produce both original and adapted screenplays. His work with Luis Buñuel alone, on dark masterpieces such as Belle de Jour (1967) and The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972), would be enough to guarantee him screenwriting immortality, but in addition he produced screenplays for such memorable films as The Tin Drum (1979), The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1988) and Birth (2004). His career encompasses almost the whole of post-new wave French cinema, as he went from being an enfant terrible to an eminence grise.

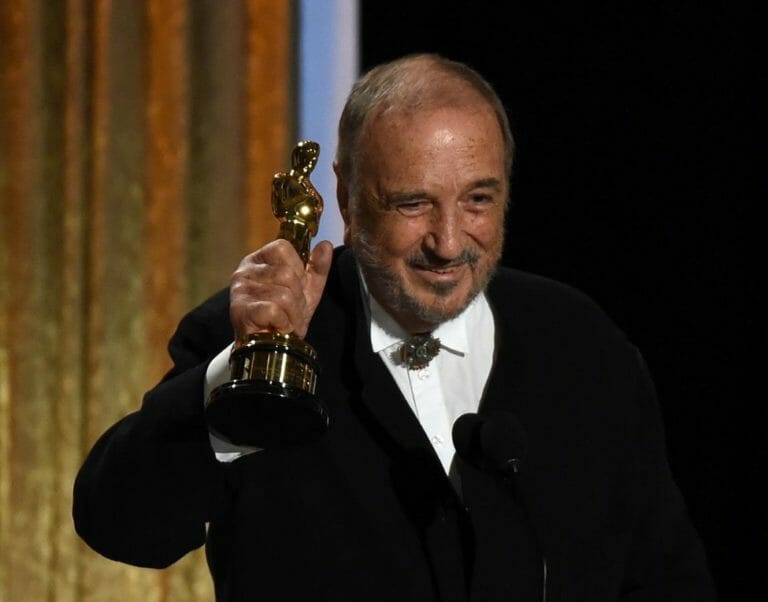

Carrière was born in 1931, the son of a farmer in the south of France, but such was his precocious ability as a child that he won a place at the École normale supérieure de Saint-Cloud, an elite French school specialising in the arts in Lyon. He seems to have moved fairly seamlessly from education into the film industry. After publishing his first novel in 1957, he met and was befriended – even mentored – by Jacques Tati, the great French comic film-maker. Intriguingly, Tati, who was always a shrewd commercial manipulator of his creative abilities, originally employed Carrière to write “novelisations” of his films, as a way of “selling” them in another medium. (Clearly, “novelisations” of movies are not just a post-blockbuster, post-1970s phenomenon.) However, Carrière soon proved his facility with words and it was another fine French clown and film-maker, Pierre Étaix, who employed him to work on scripts, including for Heureux Anniversaire/Happy Anniversary (1962), for which Étaix and Carrière won an Academy Award for Best Short Film. It was a portent of all the other accolades that would be showered on Carrière throughout his long career.

Carrière met the man to whom he was to be a muse (or at least a profound influence), Luis Buñuel, as his screenwriting career began to take off in the early 1960s. Buñuel, of course, was the great Spanish surrealist who had virtually invented cinematic surrealism nearly half a century before with his stunning short, Un Chien Andalou (1927), made with co-director Salvador Dalí. However, as Fascism’s shadow fell across Europe, including in his native Spain, Bunuel was effectively forced into exile, ending up in Mexico for several decades, before he returned to France to embark on a staggeringly creative “late phase” of his career. His closest collaborator during that near-twenty-year burst of audacious and imaginative film-making was Carrière, a man more than thirty years younger his junior but with whom he obviously enjoyed the most intimate artistic relationship.

The first product of the Bunuel-Carrière partnership was Diary of a Chambermaid (1964), based on Octave Mirbeau’s novel of 1900, which had already been filmed by Jean Renoir in America in 1946, with Paulette Goddard as the titular heroine. However, Bunuel and Carrière mined a dark seam that Renoir had left largely unexplored as their chambermaid, seductively played by Jean Moreau, was able to exert control over the wealthy family she supposedly served through her powers of invention and sexual flirtation. So many of the ideas and themes that Bunuel and Carrière would explore together in their working relationship are present and correct in this, their first film: social satire, especially the fecklessness of the wealthy; the dreamlike but disruptive power of female sexuality; and the inversion of supposed social and sexual “norms”. However, the style of Diary of a Chambermaid was relatively orthodox, at times even classical, when compared with that of their later collaborations.

The next major Bunuel-Carrière collaboration was on Belle de Jour (1967), another adaptation of a novel, this time one written by Arthur Kessel in 1928, or just a year after Bunuel had filmed Un Chien Andalou. In making Belle de Jour, Bunuel seemed to come full circle to the deliberately shocking, even provocative, style of his first masterpiece. Catherine Deneuve, who was already regarded as the embodiment of French female beauty and virtue, played the wife of a wealthy man who, because of boredom, sexual frustration or sheer wilfulness, operates as a high-class prostitute while her husband is at work. One of the most controversial films ever made (it has often been attacked by feminist film critics as simply the wish fulfilment of two men rather than the fantasy of a real young woman), it was also incredibly successful, both commercially and critically.

Throughout the rest of the 1960s, Carrière wrote scripts for other directors, including La Grand Amour/The Great Love (1969), a comedy directed by his old creative partner, Étaix, but it was clear that his most meaningful artistic relationship was with Bunuel, in whom he seemed to inspire a late, great period of creativity comparable to those of other artists in other media, from Shakespeare in theatre to David Bowie in popular music. Perhaps the greatest product of this period was The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972), which was a genuine spiritual heir to Un Chien Andalou in its fantastical depiction of a dinner party that is interrupted by everything from police and criminals to “waking dreams” of sexual encounters and gun-toting bishops. In its unusual combination of “out there” fantasy sequences and tightly controlled verbal exchanges, it embodied the differing but complementary abilities of Bunuel and Carrière.

The two men – the ageing Spanish surrealist and the younger but ceaselessly experimental French writer – made two more films together before Bunuel’s death in 1983: The Phantom of Liberty (1974); and That Obscure Object of Desire (1977). The former was an almost purely surrealist film, in which time and meaning seem to collapse into each other. The latter was almost a companion piece to Belle de Jour, with the great Fernando Rey (who had found international fame as the Marseilles drug-trafficker in charge of The French Connection) playing an old man who looks back on his life and remembers the woman he had loved, who, in a typically Bunuel-ian touch, is played by two different actresses, both of whom seem equally resistant to his romantic overtures.

Collectively, the films that Bunuel and Carrière made together represent one of the greatest director-screenwriter partnerships in the history of cinema, ranking alongside or even ahead of those made by Welles/Mankiewicz, Wilder-Brackett and Woody Allen-Marshall Brickman. As David Thomson wrote in his entry for Carrière in A Biographical Dictionary of Film (and Carrière is one of the few screenwriters who Thomson deems worthy of having their own entry in the book): “Something magical happened to Bunuel as he passed sixty. Some force, or angel, reinterpreted his spirit of surrealism for a modern age and found a way of making dreams possible with smooth photography and big stars. Carrière wrote these films and I suspect he was an angel of enablement for Bunuel on some of the smartest, funniest and flat-out best movies ever made.” “An angel of enablement” is almost the perfect description of a successful screenwriter, who somehow produces a script that “enables” a director to realise their vision.

Thomson adds in his entry on Carrière that “there is nothing that matches the Bunuel films”, which is probably true. However, that does not mean that the other fine screenplays that Carrière has produced in the thirty-or-so years since Bunuel’s death should be dismissed.

The first major film that Carrière wrote after his long and productive creative partnership with Bunuel came to an end was Volker Schlöndorff’s The Tin Drum (1979). Based on Gunter Grass’s extraordinary novel of 1959, this was another surrealistic masterpiece that Carrière seemed to adapt effortlessly for the screen, telling the story of a boy who refuses to grow up (fearing that, as an adult, he would simply become a grocer like his father) and instead becomes the manic “drummer boy” who can inspire even Nazis to dance. As with so many of his scripts for Bunuel, The Tin Drum was hugely successful both critically (winning both the Palme d’Or and The Academy Award for Best Foreign Language picture) and commercially.

Carrière was now that rarest of things – an in-demand screenwriter. So, in addition to the plays and novels that he produced throughout his career (which never quite achieved the success of his screenplays but which provided him with an invaluable creative outlet for his own ideas and interests), he worked throughout the 1980s on such esteemed films as The Return of Martin Guerre (1982), a film about a medieval missing-person’s inquiry, and Danton (1983), the story of one of the most prominent French Revolutionaries that was directed by the great Polish director Andrzej Wajda. In all these films, his mastery of story and his sympathetic depictions of even the most seemingly unsympathetic characters, such as Danton, were testament to his ability to combine surrealistic flashes with classical storytelling. Such was his lofty status that he wrote for theatre and opera as well as cinema, working with luminaries such as Peter Brook on his stage and screen versions of The Mahabharata, the ancient Indian epic.

At the end of the 20th century, after nearly four decades of writing for cinema, Carrière was almost as ubiquitous a presence in French cinema off the screen as Gerard Depardieu was on it. Indeed, some of Carrière’s finest scripts of this period were vehicles for Depardieu himself, including a marvellous Cyrano de Bergerac (1990), which gave Depardieu free rein to operate at his scene-stealing, scenery-chewing best. Another film by the Cyrano director, Jean-Paul Rappeneau, The Horseman on the Roof (1995), which told the story of an Italian nobleman who flees from his Austrian pursuers in the cholera-ravaged France of the early 19th century, is a relatively little-known classic of the period drama genre that is every bit as fantastical as its title suggests. And if there was any danger that Carrière would slip cosily into “chocolate box” cinema of the kind that his nouvelle vague contemporaries and Bunuel despised, he was also capable of writing and co-writing scripts as strange, surreal and downright odd as Max, Mon Amour (1986), in which Charlotte Rampling falls in love with an ape, and Birth (2004), one of the amazing Jonathan Glazer’s least-appreciated films in which Nicole Kidman falls in love with a 10-year-old boy who she thinks is the reincarnation of her dead husband.

Carrière probably knew all about such odd couplings from his own extraordinary working relationship with Bunuel, which will always define his career, a career that is now into its sixth decade and that encompasses the teaching of screenwriting as well as further collaborations, such as one with Umberto Eco, another elder statesman of European letters, on the future of information providers and carriers. That he was able to survive the death of his film-making kindred spirit and go on to create some of the finest cinematic adaptations of novels and plays from authors as diverse as Gunter Grass and Edmond Rostand (creator of Cyrano) is a testament to his remarkable versatility as a writer and his sheer genius with words. He was the great surrealist writer to Bunuel’s great surrealist director and their work together will endure as one of the most productive and entrancing partnerships between a writer and a director in the entire history of cinema.