By Monty Mickelson · March 30, 2017

If you read the trades, if you watch a great documentary like Tales from the Script, you come to appreciate the many different, often divergent paths that material can take on its way to the screen (or to the Netflix menu). It would be nice if this were all a meritocracy; if financing, distribution and creative initiative all flowed to the best writers with the very best ideas. Of course, it often doesn’t; and it probably never has. In his book Story, Robert McKee asserts that the spec market for feature scripts is a seller’s market (“..always has been, always will be.”)

I don’t entirely agree. I would assert that Hollywood is certainly a frantic seller’s market provided that your timing is impeccable. For instance, any time the Writer’s Guild goes on strike—say, once every 15 years or so—the resolution of that walkout sparks land rush-style bidding wars for new material. Not just any new material, mind you, but high-concept, market-ready scripts that reside in a hot-genre sweet spot; science fiction, psycho-sexual thrillers, action-driven buddy films. So when the strike ends, the checkbooks open wide. If you (and your agent) are poised to submit in that strike aftermath—well, you too can be a headline in the trades.

Obviously, agents and writers prosper in non-strike years. We’re not cicadas, and none of us has to wait fifteen years to cash in. Specs do sell and bidding wars do occur year-round, so how could that be predicated on timing? I don’t want to dwell on the negative, but bear with me here; failure may be the best market predictor of all. A colossal box office flop has a near-instant, chilling effect on its respective genre.

Case in point: westerns. In 2013, Disney went all-in with a Lone Ranger reboot helmed by the white-hot director Gore Verbinski and featuring his can’t-miss star from the Pirates franchise, Johnny Depp. The picture weathered a dismal $29 million opening weekend and Disney ultimately had to write down a purported $150 million loss. The Lone Ranger’s collapse sparked a kind of echo-failure for other western specs and period western reboots. Western projects in development or even in preproduction were all relegated to turnaround. This is not a reflection of their relative merit; they were casualties of timing.

Happily, this genre-specific market timing cuts both ways. Case in point: Jesus. In 2004, Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ did $83 million on its opening weekend and went on to earn $612 million dollars worldwide. None of this was foretold by anyone—excepting Mel. But you can bet that on the Monday morning after that hysterical success, all of those previously heathen development executives became remarkably pious in their tastes and inclinations.

As I draft this chapter, Hollywood has just experienced an even more spectacular, unforeseen hit: Beauty and the Beast. Disney, in association with Mandeville films, has just seen its fairy tale reboot open to a $174 million weekend. That figure earned Beast a number seven spot on the roster of highest all-time opening weekend gross. Beauty and the Beast made back its $160 million production costs in a scant three days. The opening broke the record for the highest-grossing domestic opening by a PG-rated film, and it was the highest-grossing weekend for a live-action Disney adaptation. I predict all of that fairy-dust and luster will fall favorably upon any similar reboots currently under consideration.

Thus, the spec market for feature scripts is partly driven by what happened at the multiplex on the preceding weekend, during the preceding month, or—occasionally—what film won Best Picture at the Academy Awards. These are all aspects of timing. There’s another happy accident of timing that could benefit your situation as well: star inclinations. It’s difficult to overstate the level of influence and prestige that a major film start can bring to a project. Stars are not just the straw that stirs the drink in Hollywood—they are the drink, the drink coaster, and perhaps even the table upon which the drink resides.

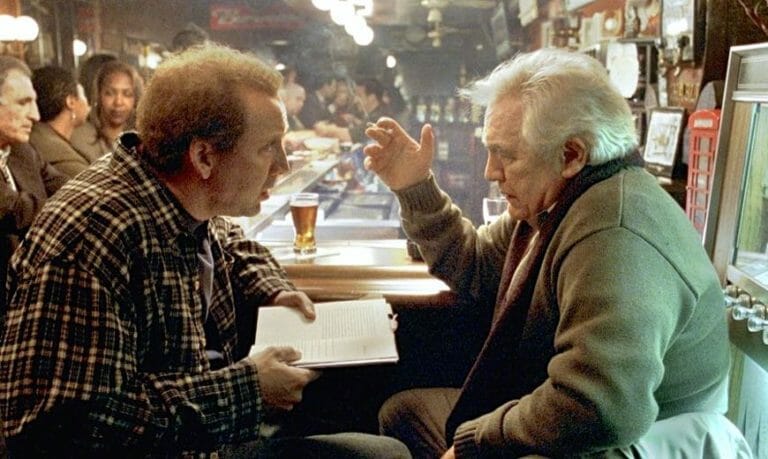

Star influence and star prestige helps attract other, more practical elements to a project, stuff like financing and foreign distribution. Having a major star attached also makes it much easier for a producer to secure an A-list director. An affiliation with a major star will get your phone calls returned, get you a parking space with your name on it, get you a better table at—you get the idea. William Goldman, in his book, Adventures in the Screen Trade, makes two essential points about film stars that are worth noting, 1.) That “one should never underestimate the insecurity of a star,” and 2.) “(Stars) live in a world in which no one disagrees with them.”

Major stars are often given offices and a development staff on a studio lot and at a studio’s expense. Some percentage of these actor-driven companies are vanity projects; an appeasement to the star with the intent of interesting him or her in other projects. Others, however, are both prestigious and prolific, generating a string of prominent—even classic—films. Clint Eastwood’s Malpaso (offices on the Warner’s lot) is a great example. Ben Afleck’s Pearl Street Films (also at Warner’s), George Clooney’s Smokehouse Pictures (Sony) and Tiny Fey’s Little Stranger (at Universal) have all transcended the “vanity project” status.

So, harking back to my point about star inclinations; when it comes to choosing projects, many film stars endorse the “two-for-them, one-for-me” ethic; that is, doing two films that are packaged by their agents and managers (that are consonant with the actor’s “image” and previous work), then doing one passion project that may deviate from their given “comfort zone”. The two-for-them, one-for-me ethic is how you might see Julia Roberts follow her turn in Ocean’s Eleven (Estimated budget: $85 million) with a supporting role in Steven Soderbergh’s experimental indie Full Frontal (Budget: $2 million). Two-for-them, one-for-me is how you find Keira Knightley following King Arthur and Love Actually with Domino—the true story of a former British fashion model who became an American bounty hunter.

The one-for-me ethic is how Matthew McConaughey ends up playing a reptilian hit-man in Killer Joe; one-for-me is how Meryl Steep accepts a role with about five minutes of screen time in The Homesman. Ditto for Jennifer Aniston’s trauma-recovery drama, Cake. I also assume that Channing Tatum was doing “one for me” when he played himself as a servile love slave (wearing a leash, walking on hands and knees) to Danny McBride’s cannibal overlord in This is the End.

Thus, three aspects of star temperament and a star’s inclinations can make for a very happy accident of timing. If a star is restive (which they often are), if they are actively shopping for that “one-for-me” project (which they periodically do), and lastly—perhaps most important—if no one on their development team, no one in their inner circle is willing to disagree with them, then suddenly you have a course correction. Suddenly, instead of sending Keira off to be fitted into her corset for the next Pirates sequel, all hands are fully immersed in the action genre, fully engaged in hearing every action pitch and reading every gritty urban thriller until they find…Domino. If you hold the rights to Domino’s life story; if you have a draft of Domino circulating and a director like Tony Scott attached—then your timing is impeccable.

Monty Mickelson has written YA feature films for cable television, and has worked as a Creative Executive for a literary manager. He also teaches screenwriting through the Recording, Radio, Film Connection and CASA Schools (RRFC) in Los Angeles.