By Martin Keady · July 26, 2017

What makes a great screenwriter? Is one great screenplay, or even a co-writing credit on a great screenplay, enough? Well, if that screenplay is Bonnie and Clyde, which David Newman co-wrote with Robert Benton, then, yes, it is.

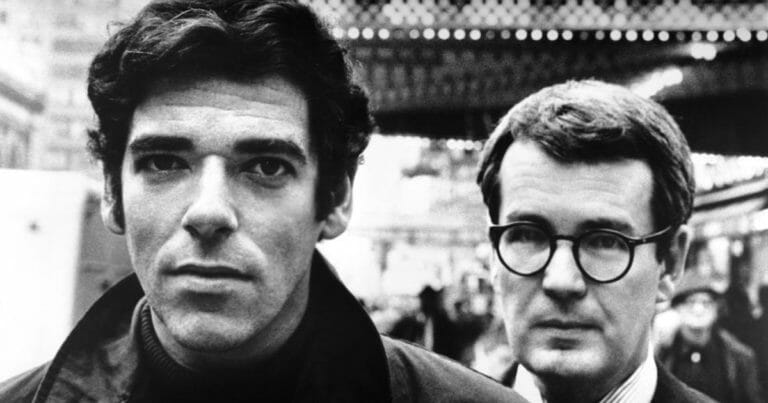

David Newman was born in New York in 1937 and studied at the University of Michigan, but it was his first serious professional job, with Esquire magazine in the early 1960s, that set him on the path to becoming a screenwriter. At Esquire, he met and befriended Robert Benton, with whom he began his screenwriting career. Together, they started work on a screenplay that would eventually become one of the most successful ever written, effectively marking the end of “Old Hollywood” (the classical studio system) and the beginning of “New Hollywood” (the era of the Movie Brats and the beginning of independent cinema). That screenplay was Bonnie and Clyde.

The story of the Depression-era gangsters was already well-known, and at least one film had been made about their exploits. However, as its name suggests, The Bonnie Parker Story (1958), focused on the female half of the crime duo. From the beginning, Newman and Benton paid equal attention to Clyde Barrow, Bonnie’s lover and partner in crime. Indeed, it was precisely the fact that Bonnie and Clyde were a couple that set them apart from all the other infamous US gangsters of the 1930s, such as John Dillinger and Al Capone. In portraying them as young lovers as well as murderous bank robbers, Newman and Benton were able to address the two great defining issues of American culture that, at least until the late 1960s, had not been accurately portrayed on screen – sex and violence.

In his seminal book on American cinema of the late 1960s and 1970s, Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, Peter Biskind argues that the true starting-point of what would become the “New Hollywood” was not actually Easy Rider, which was not released until 1969, but Bonnie and Clyde, which was released in 1967. To fully understand its seismic impact on American cinema and American culture (indeed, Western culture as a whole), it is necessary to mentally time-travel back to the largely moribund Hollywood of the early to mid-1960s. While every other popular art form – especially music, but also fashion, art and photography – was booming creatively and commercially, cinema, or at least mainstream Hollywood cinema, seemed creatively stuck in the kind of big-budget but often empty-headed big-star vehicles of the past, especially musicals. While the rest of the world was turning on and dropping out to Revolver and Pet Sounds, Hollywood’s biggest movie of the 1960s was the astonishingly conservative, indeed downright old-fashioned, The Sound of Music.

This was the world, and the cinema, that Newman and Benton were determined to jump-start with Bonnie and Clyde. From the outset, they did things differently to how most American scripts and films of the time did them. Self-consciously indebted, indeed in thrall, to the French new wave (Jean-Luc Godard’s remarkable A Bout de Souffle, or Breathless, was a huge inspiration for Bonnie and Clyde – indeed, Bonnie and Clyde could be described as an American Breathless), they wanted to take the energy and sheer inventiveness of Godard, Truffaut et al and inject it into an American movie. And to a large extent, they did.

This was the world, and the cinema, that Newman and Benton were determined to jump-start with Bonnie and Clyde. From the outset, they did things differently to how most American scripts and films of the time did them. Self-consciously indebted, indeed in thrall, to the French new wave (Jean-Luc Godard’s remarkable A Bout de Souffle, or Breathless, was a huge inspiration for Bonnie and Clyde – indeed, Bonnie and Clyde could be described as an American Breathless), they wanted to take the energy and sheer inventiveness of Godard, Truffaut et al and inject it into an American movie. And to a large extent, they did.

Newman and Benton’s iconoclastic attitude to their story was evident from the start, when Bonnie and Clyde first meet. It is a departure from the classical Hollywood “meet cute” as Bonnie witnesses Clyde trying to steal her mother’s car, but rather than reporting him to the police she is attracted to both his derring-do and his can-do attitude, especially at a time when the majority of Americans had been hopelessly cowed, if not completely broken, by the ravages of the Great Depression. Consequently, she throws her lot in with them and their crime spree begins.

Newman and Benton’s screenplay soon attracted the attention of major Hollywood players, or at least aspiring players, in particular Warren Beatty. He not only wanted to star in the film as Clyde but wanted to produce it, with his friend Arthur Penn, directing. Beatty, who was also a devotee of the great French cinema of the period, was determined to make an American movie in that vein, and in Newman and Benton’s script, which combined graphic violence with explicit sexuality, he found what he had been looking for.

Bonnie and Clyde was released in 1967 and like so many other films that end up altering movie history it was not warmly received initially, especially by the older, more traditional film critics of the period, such as Bosley Crowther of The New York Times, who struggled to comprehend its style and subject matter. As Newman himself said decades later in an interview for a book on American film-makers called New York Conversations, “He came back and wrote this scathing denunciation of the film, saying that it was offensive and moronic and it glorified crime and what was this ridiculous banjo music doing in a movie about murderers. He got everything wrong. And his ear was so… he had what we call a tin ear. He thought it was still 1945 and it was the ‘60s.” That last comment by Newman – “He thought it was still 1945 and it was the ‘60s” – beautifully sums up the generation-defining nature of Bonnie and Clyde, because in effect the movie and its script finally thrust Hollywood into the 1960s, albeit seven years too late.

The same 60s youth that was devouring The Beatles, David Bailey and Antonioni finally found the film that they were looking for, one in which young people may have broken the law but they did so at least partly because they were reacting against the stultifying, prison-like environment that they were living in. The film consequently became a huge box-office hit, making stars of all its creators, not least Newman and Benton. They were nominated for the Best Original Screenplay Oscar, but the typically conservative Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences opted instead for a far more traditional offering, Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner, as much to pay homage to its stars, Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn, as for any “originality” in its writing.

On the back of Bonnie and Clyde’s success, Newman and Benton left Esquire and became one of the most sought-after screenwriting teams. Their first script after Bonnie and Clyde was a Western, There Was A Crooked Man… (1970), that was most notable for its director, Hollywood legend Joseph L. Mankiewicz, who had directed classics such as All About Eve (1950) and Guys and Dolls (1955). Unfortunately, There Was A Crooked Man… was no such classic, especially in what was then the Golden Age of anti-Westerns, such as Butch Cassidy and The Sundance Kid and The Wild Bunch, which had both been released a year earlier. Effectively, There Was A Crooked Man… set the template for the rest of Newman and Benton’s screenwriting career. While they would achieve considerable commercial success, they never quite managed to replicate the commercial and artistic success of Bonnie and Clyde.

On the back of Bonnie and Clyde’s success, Newman and Benton left Esquire and became one of the most sought-after screenwriting teams. Their first script after Bonnie and Clyde was a Western, There Was A Crooked Man… (1970), that was most notable for its director, Hollywood legend Joseph L. Mankiewicz, who had directed classics such as All About Eve (1950) and Guys and Dolls (1955). Unfortunately, There Was A Crooked Man… was no such classic, especially in what was then the Golden Age of anti-Westerns, such as Butch Cassidy and The Sundance Kid and The Wild Bunch, which had both been released a year earlier. Effectively, There Was A Crooked Man… set the template for the rest of Newman and Benton’s screenwriting career. While they would achieve considerable commercial success, they never quite managed to replicate the commercial and artistic success of Bonnie and Clyde.

Nevertheless, the next few films that they worked on after There Was A Crooked Man… were noteworthy, if only for their disparate nature. First, there was What’s Up, Doc? (1972), Peter Bogdanovich’s homage to ‘30s screwball movies, which they co-wrote with Bogdanovich himself and Buck Henry, who had been one of the screenwriters of The Graduate (another classic of the “new” Hollywood). Then, they were part of what is perhaps the most remarkable group of screenwriters ever to work on one movie, when they were listed, alongside John Lennon, Kenneth Tynan and a youthful Sam Shepard, as one of the many co-writers of Oh! Calcutta! (1972), the film of the “sex-sketch show” that had been such a hit on Broadway.

By now, however, the strains and tensions were beginning to emerge in the Newman-Benton writing relationship. Benton, like so many screenwriters, longed to direct and finally got the chance with another Western that he and Newman had written, Bad Company (1972), which drew explicit parallels between the Vietnam draft-dodgers and those American men who, more than a century earlier, had fled west to escape being drafted into the US Civil War. Although the film was only a modest success, both at the box office and critically, it none the less convinced Benton that in the future he should try to write scripts that he would then direct. Consequently, Newman, who was only interested in writing, had to find another screenwriting partner. Fortunately, he did not have to look far, as he eventually settled on writing with his wife, Leslie, and they went on to become one of the most successful husband and wife screenwriting duos.

With Bonnie and Clyde, Newman had done much to shape late 1960s cinema, which eventually flowered into what is often described as Hollywood’s second Golden Age – the 1970s. Even the greatest film of that period, The Godfather (1972), paid homage to Bonnie and Clyde, with Sonny Corleone being gunned down in remarkably similar fashion to Bonnie and Clyde. A decade later, however, Newman would achieve his second great period of screenwriting success with his wife but in a completely different field. Indeed, he was a major contributor to the rise of the blockbuster movie that would eventually come to sweep aside the more personal and artistic movie-making of the early to mid-1970s. He did so with Leslie as the co-writers of the original Superman movies.

On the surface, there might appear to be little to link Bonnie and Clyde with the Superman trilogy (1978 to 1983), but Newman had actually been involved in scripting Superman stories even while he and Benton were trying to sell Bonnie and Clyde. Together, they had worked on the book of a Superman musical called It’s A Bird… It’s A Plane… It’s Superman, which was a considerable Broadway success in the late 1960s. When Newman and his wife were hired as part of the team of writers working on the first Superman movie (1978), alongside Benton (who was prepared to forego directing for an enormous pay cheque) and Mario Puzo, who wrote The Godfather novel, they inverted the musical’s convoluted title to create the tagline for the movie: “Is it a bird? Is it a plane? No, it’s SUPERMAN!”

On the surface, there might appear to be little to link Bonnie and Clyde with the Superman trilogy (1978 to 1983), but Newman had actually been involved in scripting Superman stories even while he and Benton were trying to sell Bonnie and Clyde. Together, they had worked on the book of a Superman musical called It’s A Bird… It’s A Plane… It’s Superman, which was a considerable Broadway success in the late 1960s. When Newman and his wife were hired as part of the team of writers working on the first Superman movie (1978), alongside Benton (who was prepared to forego directing for an enormous pay cheque) and Mario Puzo, who wrote The Godfather novel, they inverted the musical’s convoluted title to create the tagline for the movie: “Is it a bird? Is it a plane? No, it’s SUPERMAN!”

David and Leslie Newman worked on all three Superman movies; indeed, they were the only writers on Superman III (1983). However, despite the extraordinary financial compensations of working on such a series, there was relatively little artistic fulfilment, and certainly none on the scale that Newman had enjoyed with Bonnie and Clyde. And after the Superman films, things only got worse, as Newman contributed to such appalling fare as Santa Claus: The Movie (1985) and, most cringeworthy of all, Moonwalker (1988), the Michael Jackson star vehicle for which Newman was credited as the sole writer of the “Smooth Criminal” section.

The irony, of course, was that Newman, alongside his original writing partner, Benton, had arguably created the original smooth criminals in Bonnie and Clyde. For that alone, he is deserving of deification as a screenwriter, even if he never again matched the brilliance of that era-defining and Hollywood-redefining script.

—