By Martin Keady · September 22, 2017

The Story Behind The Screenplay is a series by Martin Keady that examines the origins of some of the greatest screenplays ever written. It continues with an examination of the story behind one of the greatest Shakespeare films ever made, Grigori Kosintsev’s Hamlet.

Shakespeare’s Hamlet is not only (by common, if not universal, consent) the greatest play ever written but the basis for some of the greatest Shakespeare screen adaptations ever made, especially Laurence Olivier’s Oscar-winning version (1948). However, Olivier himself was one of the first to heap praise on a much less well-known screen Hamlet, namely the great Soviet-era adaptation of the play, Gamlet (1964). Its creator, Grigori Kosintsev, was one of the finest screen directors of Shakespeare and the story behind his cinematic adaptation of Shakespeare’s greatest play, which involves a cast list of famous writers, famous composers and famous dictators, is one of the most fascinating “back stories” of any Shakespeare movie.

Kozintsev’s life and career spanned almost the entire length of the 20th century and so coincided with the Soviet era in Russia, when the Communist Party first seized power from the Tsar and then ruled over the country for more than seventy years. Kozintsev died before the end of the Soviet era, when the Communists finally lost control over Russia, but his two great Shakespeare films, Gamlet (1964) and Korol Lir (King Lear) (1971), which were made near the end of his career and life, are among the most profound artistic examinations of Soviet-era totalitarianism.

Kozintsev was born in 1905 in Kiev, which is now part of Ukraine, a country that is obviously still suffering from the convulsions that followed the collapse of the Soviet Union. Consequently, Kozintsev’s early life and artistic career were lived and acted out against the backdrop of the Communist Party taking control of Russia and instantly implementing sweeping social, economic and even artistic reforms.

Kozintsev was born in 1905 in Kiev, which is now part of Ukraine, a country that is obviously still suffering from the convulsions that followed the collapse of the Soviet Union. Consequently, Kozintsev’s early life and artistic career were lived and acted out against the backdrop of the Communist Party taking control of Russia and instantly implementing sweeping social, economic and even artistic reforms.

The young Kozintsev was clearly precocious, studying first at the Kiev School of Art and then at the famous Academy of Arts in Petrograd (now St. Petersburg, having been Leningrad in between). Although he formally studied art, he was always fascinated by theatre, particularly Shakespeare, organising experimental performances from an early age, including of Gogol’s play, Marriage, in which a civil servant contemplates the personal and financial difficulties of taking a wife (exhibiting Hamlet-like indecision as he does so). Among Kozintsev’s direct contemporaries in Petrograd were several luminaries who would go on to become some of the greatest artists of Soviet Russia, including the theatre director and theorist Vsevolod Meyerhold, the film director Sergei Eisenstein and the composer Dmitri Shostakovich. It was with Shostakovich that Kozintsev was to have the longest and most fruitful personal and professional relationship, as Shostakovich ultimately scored Kozintsev’s Shakespeare films, in the process writing some of the finest film music, and particularly Shakespearean film music, ever written.

Having completed his studies at the Academy, Kozintsev found work at the Lenfilm studios in the city, which was part of the newly nationalised state film industry. He worked alongside the likes of Eisenstein and Shostakovich, but his closest friend and associate at this time was Leonid Trauberg, a fellow Ukrainian with whom Kozintsev made all his early films (indeed, all his films until about 1947). These included a 1926 adaptation of another Gogol work, the short story called “The Cloak” or “The Overcoat”, about the attempts of a 19th century Government clerk first to buy and then to retrieve (after it is lost) the new coat that he desperately needs to protect him against the Russian winter.

Unlike many Russian artists of the Soviet era, Kozintsev managed to survive the worst excesses of Stalinism. This was partly because much of his creative energy was dedicated not solely to film-making but to teaching at academic institutions in Petrograd (which by now was called Leningrad after the founder of the USSR). What is particularly intriguing is that Kozintsev taught both cinema and Shakespeare, writing about the great playwright as well as film directors such as Charlie Chaplin and his former contemporary, Eisenstein. In retrospect, it is tempting to see this period in Kozintsev’s life and career as a period of research and even groundwork for the pair of Shakespeare films that he would finally direct near the end of his life.

Another crucial element of this research or groundwork was his close collaboration with Boris Pasternak, the great author (notably of Dr Zhivago, which itself would go on to become a major Hollywood film after the manuscript was smuggled to the West and translated into English) and, crucially, translator of Shakespeare. In the early 1940s, Pasternak translated a number of Shakespeare’s plays into Russian, including Hamlet and King Lear, and these translations formed the basis of Kozintsev’s productions of the plays, first on stage and then, much later, on film.

Kozintsev first staged Hamlet and King Lear in the early 1940s, but the Nazi invasion of Russia put his work of adapting Shakespeare on hold until after the war had ended. And it was not only the Nazis who Kozintsev had to be wary of. Stalin himself was famously suspicious of any production of Hamlet, because he allegedly feared comparisons being made between himself and Shakespeare’s usurper, Claudius. Stalin may not have killed Lenin with his own hands, but he had seized control of the Communist Party after Lenin’s death and he certainly had several of his rivals for power, including Trotsky, eliminated.

Kozintsev first staged Hamlet and King Lear in the early 1940s, but the Nazi invasion of Russia put his work of adapting Shakespeare on hold until after the war had ended. And it was not only the Nazis who Kozintsev had to be wary of. Stalin himself was famously suspicious of any production of Hamlet, because he allegedly feared comparisons being made between himself and Shakespeare’s usurper, Claudius. Stalin may not have killed Lenin with his own hands, but he had seized control of the Communist Party after Lenin’s death and he certainly had several of his rivals for power, including Trotsky, eliminated.

Consequently, Stalin did not want the Kremlin to be presented as another Elsinore – the corrupt centre of a corrupt state. In particular, he punished another of Kozintsev’s former contemporaries in Petrograd, Meyerhold, who had always dreamed of performing Hamlet but was forbidden from doing so. Worse still, Meyerhold was eventually arrested, tortured and executed for supposed “anti-Soviet” sentiments in his work. After his murder in 1940, it was said that Meyerhold had wanted as his epitaph: “Here lies a man who never played or directed Hamlet”. It was only after Stalin’s own death in 1953, and the subsequent easing (relatively speaking) of Soviet oppression of its artists, that Kozintsev’s vision of a “great Russian Shakespeare” could finally begin to develop fully.

Kozintsev’s films of Hamlet and King Lear were the last two films he ever made, at the end of a long and illustrious career as a film-maker that included not only the aforementioned adaptation of Gogol but other adaptations of classic works of literature, including Don Quixote, which he made in 1957. However, it is on these two great Shakespeare films that his reputation largely endures, especially in the West, and deservedly so, because they are among the finest adaptations of Shakespeare ever filmed.

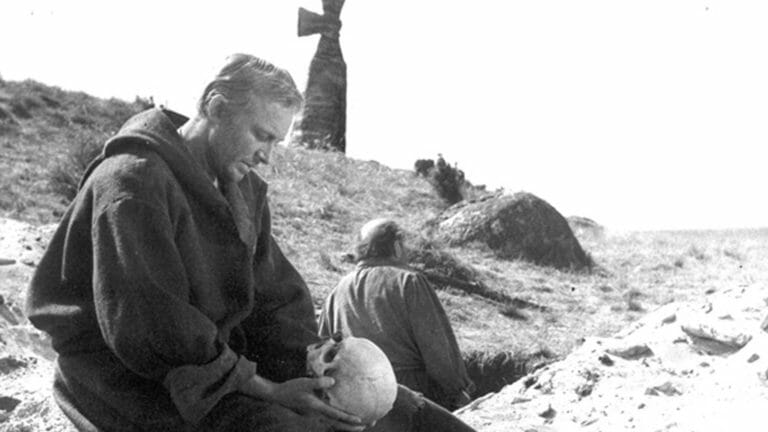

Hamlet was released in 1964 and was one of the major Russian films of its time. Kozintsev marshalled not only his own creative forces (which had necessarily long been suppressed under the brutal reign of Stalin) but those of a stellar list of collaborators: Iosif Shapiro (as assistant director or co-director, who would also work with him on King Lear); his lifelong friend, Shostakovich, to write the music (again, Shostakovich would also compose the music for King Lear); and a superb cast of Russian actors, including Innokenty Smoktunovsky as a smouldering male blonde bombshell of a Hamlet and Mikhail Nazvanov as a charismatic, even glamorous, Claudius.

There are two key sayings of Kozintsev that are vital to an understanding of his Shakespeare films. The first was that he famously said that the main advantage of filming Shakespeare, as opposed to staging him, was not that you could show men on horse-back but that you could show them in close-up, so that you could literally see them think. And this he does continually, to stunning effect, in both Hamlet and King Lear, notably when he is filming Hamlet’s soliloquies, especially the “To Be Or Not To Be” soliloquy. Secondly, Kozintsev, like many Russian writers and critics, argued that Shakespeare was a great natural poet, intimately knowing and describing the world of nature that is largely forgotten by 20th century urban man, and so it was vital to film his plays in nature. Again, Kosintsev does this to astounding effect in both Hamlet and King Lear, in which he convincingly creates whole cinematic “Shakespeare-worlds”: in Hamlet, the world of a cliff-top castle; in King Lear, the world of a huge, sprawling, desolate kingdom, which has as much in common with Soviet Russia and its satellites as it does with early medieval England.

There are numerous cinematic and Shakespearean delights in both of Kozintsev’s Shakespeare films, and the best thing that I can do is to urge any reader to see them (notwithstanding the difficulty of accessing English-subtitled versions of the films). In particular, their openings, while very different in some respects, are similarly effective in introducing the viewer to the distinctively Russian cinematic Shakespeare-worlds that Kozintsev creates.

There are numerous cinematic and Shakespearean delights in both of Kozintsev’s Shakespeare films, and the best thing that I can do is to urge any reader to see them (notwithstanding the difficulty of accessing English-subtitled versions of the films). In particular, their openings, while very different in some respects, are similarly effective in introducing the viewer to the distinctively Russian cinematic Shakespeare-worlds that Kozintsev creates.

Kozintsev’s Hamlet does not open, as the play does, with the Ghost appearing to the soldiers guarding Elsinore, but with the sea that surrounds Elsinore. (Like all Shakespearean film-makers, especially those filming Hamlet, Kozintsev had to make major cuts to the original play to reduce it to an acceptable running time for a movie audience.) We hear a bell tolling, which eventually segues into the beginnings of Shostakovich’s superb, strident score, and then we cut to Hamlet on horseback, hurrying towards Elsinore with Horatio. He is immediately ushered into the castle, and the drawbridge is raised again.

What is most telling, however, and it is something that I cannot recall seeing in any other Shakespeare film, or indeed any other film featuring a castle, is that Kozintsev shows the men (the poor men, or peasants) literally struggling to raise and lower the drawbridge. He does this time and again throughout his Shakespeare films, particularly in King Lear: he shows the subjects of these kingdoms, the subjects of Claudius and Lear, who are so often absent from any reading or stage production of the plays. Kozintsev literally peoples his Shakespeare-world, more than any other Shakespeare film-maker and arguably even more than Shakespeare himself, showing how the actions of the few (the rich and powerful) impact on the many (the poor).

Kosintsev is credited as one of the three screenwriters of his Hamlet movie, alongside Shakespeare himself and Pasternak, and the individual stories of these three writers had an enormous influence on the film. Kosintsev and Pasternak had endured similarly long and arduous struggles to achieve artistic freedom under the Soviet state, while Shakespeare’s own struggle was a far more personal one. Hamlet is many things, but it is surely also his lovesong (an unrequited one) to his own dead son, Hamnet, who died, probably of the plague, in 1596, aged only 11. For Shakespeare, the loss must have been incalculable. Not only had he lost his only son and heir (in an age when sons were valued infinitely higher than daughters), but it is likely that he had not even spent much time with him before he died, given that Hamnet’s sole decade of life had coincided with Shakespeare’s own flight from Stratford on Avon (apparently, it is often said, because he had been caught poaching on a nobleman’s land) and his subsequent reinvention of himself as a player and playwright in London.

What is perhaps most remarkable about Shakespeare’s original play, Hamlet, is that it is an inversion of the actual events of Shakespeare’s own life. Whereas Shakespeare mourned the death of his son, in the play he does not depict a father grieving for a son he hardly knew but a son grieving for a father who had been a distant, if not mythical, figure who he had barely known personally. This is entirely typical of Shakespeare’s genius at taking original source material (in the case of Hamlet, several earlier versions of the story, including one now known as Ur-Hamlet) and reshaping it, often by completely altering or transforming its core structure, into something far greater than its origins.

What is perhaps most remarkable about Shakespeare’s original play, Hamlet, is that it is an inversion of the actual events of Shakespeare’s own life. Whereas Shakespeare mourned the death of his son, in the play he does not depict a father grieving for a son he hardly knew but a son grieving for a father who had been a distant, if not mythical, figure who he had barely known personally. This is entirely typical of Shakespeare’s genius at taking original source material (in the case of Hamlet, several earlier versions of the story, including one now known as Ur-Hamlet) and reshaping it, often by completely altering or transforming its core structure, into something far greater than its origins.

In Kosintsev’s film of Hamlet, Shakespeare’s own sense of loss at the death of his son is always evident, but there are numerous other marvels, too. They include a wondrous lead performance by Smoktunovsky (even Olivier, the second best screen Hamlet, conceded that Smoktunovsky was the best); a depiction of an Elsinore/Kremlin (a Kremlinore?) that is all walls and shadows; a superb rendition of the soliloquies, especially the “To Be Or Not To Be” soliloquy, which, though much reduced from the stage version, is a masterpiece of compression, proving that the cinematic voiceover is the artistic heir of the stage monologue or soliloquy; and finally a devastating ending, featuring a powerfully authentic fencing match (screen fencing matches are always so much more convincing than their stage equivalents), which ends with Hamlet’s famous final soliloquy literally reduced to “The rest is silence”, before he sits down and dies in a hole in the castle-wall that looks uncannily like a throne made of stone (the only throne he will ever ascend).

Ultimately, Kozintsev’s Hamlet and King Lear cry out to be seen together, as the perfect Shakespearean cinematic double bill. If they are viewed in this way (as I myself have done in researching this piece), they throw up fascinating questions and correspondences about what are generally regarded as Shakespeare’s two greatest plays. In particular, they both emphasise the visual majesty of Shakespeare’s storytelling. I had to oscillate between watching old, faded VHS copies of the films and unsubtitled online versions, but in both formats the storytelling (presupposing only a basic knowledge of the play) was still clear, showing how foreign-language films of Shakespeare, like those of Kozintsev, can be enjoyed almost as silent movies.

For all the latest from The Script Lab, be sure to follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.