By Ken Miyamoto from ScreenCraft · May 29, 2018

Conflict is the driving force behind any great screenplay — but what is cinematic conflict and how do screenwriters conjure enough of it to keep readers and audiences invested in their stories and characters?

Cinematic conflict differs from story and character conflict found in the literary platform with novels, novellas, and short stories.

In the literary platform, conflict can be presented through a wide variety of literary tools. The description of events through the author’s prose can set up situations and scenarios of two opposing forces — be it physically or intellectually — and describe the outcome. But the author’s primary tools to showcase conflict can be found within the detailed background of the characters, settings, and situations that they have the freedom to describe at length. The author also has the freedom of using inner dialogue or the presentation of inner thoughts of their characters to portray inner conflict and how exterior conflict affects that inner conflict.

Screenwriters don’t have the freedom to use those tools.

Cinematic conflict has to be presented in a visual form where the audience can witness both the interior and exterior conflict with their own eyes, without the crutch of using overly long voice-over or exposition.

Cinematic conflict is every point of opposition between two forces (physical or intellectual) as well as the repercussions of that opposition — all within full view of what can be seen on the screen, be it through a movie theater, television, or device.

Screenwriters can’t convey conflict using background and inner thoughts or explanation of inner thoughts — that’s literary conflict.

Instead, screenwriters are tasked with presenting conflict on screen through scene descriptions, character actions and reactions, and dialogue. While dialogue is something we hear and could certainly — in lesser scripts — be used to replace literary prose to describe background information, past history, and inner thoughts, the best scripts and films show rather than tell.

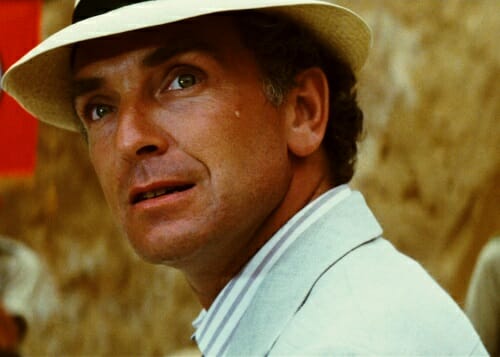

In Raiders of the Lost Ark, we see the many physical obstacles Indiana Jones must overcome.

We also see the many intellectual opposing forces that are working against him.

As well as emotional obstacles.

As we see these opposing forces working against him, we, in turn, see his reactions to those opposing forces.

The actions and reactions of Indiana Jones comprise the cinematic conflict within the screenplay. We see that he is in search of the Ark of the Covenant. We see that the Nazis have hired his nemesis to find the Ark before Indiana does. We see that in order to gain an advantage over his foes, Indiana must confront and partner with a past love that he scorned years ago.

These characters and events lead to multiple cinematic conflicts in the forms of physical obstacles (traps, snakes, soldiers) and intellectual obstacles (puzzles, history, myth).

All of these elements are portrayed on the screen for the audience’s eyes to see.

And this cinematic conflict is present in all genres — drama, comedy, horror, etc.

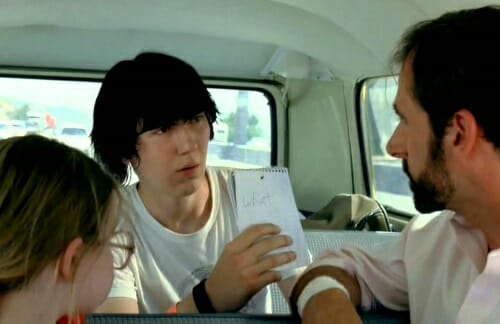

In Little Miss Sunshine, we see that little Olive is obsessed with partaking in a beauty pageant. And we see that she clearly does not fit the stereotypical and usually desired look for such competitions.

We see that her grandfather Edwin is a drug addict.

We see that her uncle is recovering from a suicide attempt.

We see that her father is a failed motivational speaker.

We see that her big brother is living under a vow of silence until he can accomplish his dream of becoming a test pilot.

We see that her mother is a struggling and overworked mother dealing with all of these characters.

And we see all of those character elements compounded into a small VW bus as the family decides to help Olive realize her dream.

Cinematic conflict is what we see on that screen. We can’t rely on dialogue to share inner thoughts. We can’t rely on bad exposition in dialogue or title card form to explain things away.

Physical conflict is easy to show. Emotional conflict is all about showing us the tears, the anger, the joy, and whatever emotion is triggered during a character’s actions and reactions to the obstacles at hand. But we have to see it.

The very definition of cinematic is something of, relating to, suggestive of, or suitable for motion pictures. Motion pictures — movies or television — are part of a visual medium. Thus, cinematic conflict must be ever-present on the screen.

Conflict is often mistaken as character altercation — two opposing forces in a direct altercation with each other. While that certainly comes into play, great conflict is so much more that.

Conflict is most simply defined as the meeting of a character’s goal and the obstacle that gets in their way. And this notion is enhanced by throwing as many obstacles into that equation. The more obstacles, the more the conflict. The more we see those obstacles, the better the cinematic conflict within your scripts.

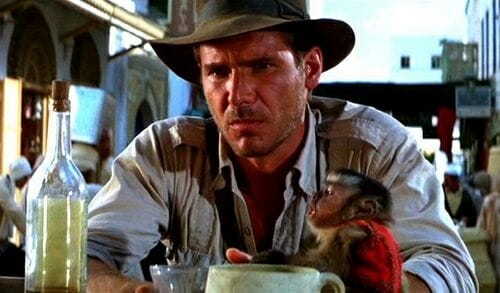

What is in the way of Indiana Jones? A lesser version of the Raiders of the Lost Ark script would have Indy simply going through the various steps to locate the Ark. Maybe he has a map and simply follows the directions.

His journey may take him through jungles and over land and sea.

His journey may task him with connecting with people that can help him unearth the Ark from its hiding place.

But if that’s all there is within the script, there’s little to no conflict.

So what screenwriter Lawrence Kasdan, producer George Lucas, and director Steven Spieberg did to create cinematic conflict was to inject the aforementioned conflicting elements that are in the way of Indy’s quest.

He has to race against time because his nemesis and the Nazis who hired him are trying to find the Ark as well. He has to deal with the added conflict of having his ex-beau Marion in tow, first dealing with her adversarial stance and then having to deal with his newfound love and attraction to her as his enemies threaten not only his life, but hers. And then we have car chases, towering Nazi soldiers, snakes, explosions, and supernatural events that Indy must face as surviving.

That’s how you create cinematic conflict.

And in the case of a small drama like Little Miss Sunshine, yes, screenwriter Michael Arndt surely could have presented the simple story of a little girl traveling to a beauty pageant and dealing with the confrontation of those taking part in and officiating the pageant as they react to her unconventional look and approach.

However, he was wise enough to inject more cinematic conflict by having each and every member of her family pack into a small VW bus during a time where each and every one of them is struggling in their own lives. And those struggles directly affect Olive’s journey from her home to her goal of winning a beauty pageant. The bus breaks down. The brother is crushed to learn that he can’t join the Air Force. The uncle is struggling with depression. The father is putting his own dream in front of everyone else’s. And then, yes, the grandfather goes and dies.

These are just a few of the obstacles that are getting in the way of Olive and her goal.

To create cinematic conflict, all that you need to do is present obstacles that stand in between your protagonists and their goal. And those obstacles don’t always have to be physical. They can be emotional.

In Raiders of the Lost Ark, when Marion is presumed dead, we have the added element of Indiana Jones dealing with her loss. This leads to the moment of his nemesis confronting him when he’s at his lowest. All hope is lost.

And then when Indy discovers Marion alive, the conflict is enhanced because not only does he have to locate the Ark before the Nazis, he also has to save Marion’s life as well because of his emotional connection to her.

To create engaging cinematic conflict, all that you need to do is simply follow these steps:

That’s the fun of screenwriting, when you ask yourself, “What can I do to make their journey towards their goal more and more difficult?”

An excellent analogy to use is The Burning Tree analogy.

You want to have an opposing force chase your characters up into a towering tree. As they figure out how to get down while evading the threat that chased them up there in the first place, you set that tree on fire. Now they’re faced with the threat of dying from the fall as they try to jump to safety to escape the flames, or being burned alive if they’re too scared to jump. And then, as if that wasn’t enough, you start throwing rocks at them. And then they discover that the tree is full of termites and isn’t going to last as long as they thought it would.

The first act is them being chased up that tree.

The second act is that tree being set on fire.

The middle of that second act is rocks being tossed at them while the fire climbs higher and higher.

The end of the second act is when they discover the tree is full of terminates and the very branches they are clinging to are rotting from within and fueling the fire even more.

The third act is them finally figuring out a solution and acting on it.

That’s cinematic conflict. Every few pages the characters need to be presented with new or evolved obstacles that they must face. And the stakes have to be heightened by multiple obstacles throughout.

Bad exposition would have you using flashbacks and dream sequences to convey conflict. Bad exposition would also have you use dialogue to explain why the protagonist feels threatened.

What’s even worse is watching two characters agree on a piece of information within the plot and story — it’s weak and boring. It’s not cinematic because there’s no conflict present.

But while exposition is something you want to avoid at all costs, it’s also necessary within a story. But only when used wisely. If you have to convey information, have two or more characters disagree on it. Or have them disagree with how to react to that shared information.

In Season Two of The Walking Dead, Shane and Rick are best friends that want the same thing — to keep the group safe. They are always presented with the same information and same situation. However, they both react in different ways. They disagree. They have different solutions in mind.

Same information, same situation. But cinematic conflict is created when they are at odds with the interpretation of the information and the implementation of a possible solution.

So we’ve communicated how simple and easy it is to create excellent and engaging cinematic conflict. The last lesson is to make sure that while you are bombarding your characters with conflict after conflict and obstacle after obstacle on their physical or emotional journey (preferably both), those elements are slowly growing bigger and bigger.

If Raiders of the Lost Ark simply showed Indy facing booby traps, it would get pretty old. The audience would lose interest. But as written and produced, the conflict grew and grew as the story went along.

We first met Indy as a treasure hunter. Then he was tasked with finding a treasure that could threaten not only his country and its allies, but the world as he knew it.

He starts to hunt for the Ark by following the clues. This leads him to Marion. Now the conflict has grown because he has to face his past relationship with her as well. Then we discover that Indy’s nemesis is on the hunt for the Ark as well. His adversary adds more conflict because it’s no longer just Indy against some Nazis — it’s Indy against an equal. Later on, Indy finds the Ark and must unearth it from a deep, dark cave. But the floor is full of snakes — his greatest fear. And then the Ark is taken from him and Marion is thrown into the cave as they are locked in, buried alive. With thousands of venomous snakes.

The conflict builds and builds to the point where supernatural forces are unleashed and Indy and Marion are powerless to survive. It’s out of their hands.

You must constantly build and build with obstacles that are increasingly more threatening than the previous.

And if it’s a drama, you handle that through emotional obstacles. And if it’s a comedy, you put those characters through emotional and physical obstacles and witness the hilarity of those characters reacting to those situations.

Cinematic conflict is something that all screenwriters need to master. We need to see it. We need to see a lot of it. We need new and evolving conflict and obstacles every few pages. And this applies to each and every type of screenplay you write — whether it’s a big action spectacle or small indie drama.

Cinematic conflict is everything.

Ken Miyamoto has worked in the film industry for nearly two decades, most notably as a studio liaison for Sony Studios and then as a script reader and story analyst for Sony Pictures. Make sure to read his growing archive of posts at ScreenCraft for more inspiration.

He has many studio meetings under his belt as a produced screenwriter, meeting with the likes of Sony, Dreamworks, Universal, Disney, Warner Brothers, as well as many production and management companies. He has had a previous development deal with Lionsgate, as well as multiple writing assignments, including the produced miniseries Blackout, starring Anne Heche, Sean Patrick Flanery, Billy Zane, James Brolin, Haylie Duff, Brian Bloom, Eric La Salle, and Bruce Boxleitner. Follow Ken on Twitter @KenMovies

For all the latest from The Script Lab, be sure to follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.