By Ken Miyamoto from ScreenCraft · September 9, 2018

What are the best and most effective ways to write cinematic scene description that keeps the reader invested, engaged, and lost in the visuals of your movie?

The four basic elements of screenwriting format are scene heading, scene description, character name, and dialogue. Anything else — camera directions, transitions, and parentheticals — rarely do anything beyond creating more for the reader to read and process, which slows down the read of the script. Those elements can be utilized, but only sparingly so and only when completely necessary.

Scene headings are simple. They consist of three elements — interior or exterior, location, and day or night (with some variations).

Read ScreenCraft’s Screenwriting Basics: The Keys to Writing Correct Scene Headings!

Character names are obvious. Dialogue is fairly straightforward.

But it’s scene description that truly holds the key to the success of your screenplay, specifically from the standpoint of how easy it is for the reader to truly experience your story in cinematic fashion. You want the reader to be able to decipher the visuals you are describing in your scene description as quickly as possible — as if they were reels of film flashing before their eyes.

Sadly, most novice screenwriters fail to understand the importance of writing cinematically. Instead, they either focus on directing the camera or go into specific detail with long-winded scene description.

Here are five best practices to help you write effective scene description that will make your screenplays become the coveted page-turners that script readers crave for.

Your job is very simple as a screenwriter — convey what the reader is supposed to envision in broad stroke form, and do so as quickly as possible.

You’re not writing a novel. You’re not using the scene description to go into specific detail about the sets, the locations, the character’s wardrobe, each and every movement, etc.

The fewer words you use to describe a visual the better. That’s how cinematic screenplays are born. A reader would rather read a conventional screenplay that reads in a way where they feel they watching a movie, as opposed to a more original screenplay that feels that they’re reading a long novel. The best thing you can do as a screenwriter is offer them that latter content partnered with a cinematic read.

Anyone can write a long, multi-paragraph description of a setting or action sequence where you articulate descriptive sights, sounds, and atmosphere — and then put together poetic descriptions of each of those details.

In a screenplay, there’s no room for that type of writing. Readers don’t care. You instead need to embrace the art of compressed imagery where you eliminate those elongated elements from your prose and get to the point so the reader can see that visual and move onto the next as quickly as possible.

To master compressed imagery, you have to learn how to whittle everything down to the core. And when you think you’ve accomplished that, whittle it down even more.

Here’s an example.

This scene description block isn’t the worst we’ve seen by any means. Two sentences in one block and one long sentence in another. A lesser writer would have used another paragraph to go further into detail, trying to capture some sort of particular atmosphere for what is basically one image for the reader to visualize.

However, take a look at this whittled-down version.

If you compare the two, they both are describing the same visual. The second example just gets to the point without poetic detail.

Sure, that rewrite would only save you a couple of lines within your script, but if you embrace this Less Is More mantra and apply that to each and every line of scene description in your script, the difference will be substantial.

And the most important aspect will be describing each visual quickly enough where the reader can process it at lightning speed. Hence, you’ll be offering them more effective scene description.

But that’s not all you can do.

A block of scene description refers to the amount of “ink” used before a blank space. It could be just one sentence, two, three, four, or (hopefully not) more.

The first scene example above had two blocks of scene description.

The problem many screenwriters have is that their blocks of scene description are often very thick and long. They pack multiple visuals into one single block of scene description. This drastically slows the read down. Here’s how you can fix that.

Think of each block of scene description as a visual that you are throwing at the reader.

This is what I want you to see.

Now you see this.

Now this happens.

If you pay attention to how those three sentences read, you’ll notice that there’s a beat to that.

Boom Bada.

Boom Bada.

Boom.

When you have visuals crammed together in long paragraphs, the reader’s brain interprets that block differently, despite the same description being used.

This is what I want you to see. Now you see this. Now this happens.

When those three sentences are separated into their own short blocks of scene description, they create a rhythm. When they are garbled together into one block of scene description that consists of three back-to-back sentences, the rhythm is lost.

It reads more like Boombadaboombadaboom.

Do you see the difference? Read those different examples over and over again, and you’ll begin to understand that screenplays have a rhythm to them. A script that embraces the Less Is More mantra and spaces out those blocks of scene description is easier to read and offers a more cinematic experience.

Anytime you have big blocks of scene description with multiple sentences bunched together, space them out. Let each block be a single visual that you are throwing at the reader and do your best to keep each block at no more than two sentences.

And yes, fragments are very welcome.

Scene description is all about setting the stage. Part of that is sharing the specific times, dates, and locations if necessary.

Many screenwriters make the mistake of including that information within the scene heading.

Readers have trained themselves through the format to pay less attention to the scene heading — because it’s very easy to read INT. LOCATION – DAY — and more time on the scene description. So if you’re trying to convey specific times, dates, and locations, you want to utilize the scene description to accomplish that so nothing is missed or forgotten.

Below are examples of elements that should not be in scene headings.

Instead, you want to share those dates within the first line of the scene description after the heading.

If the dates are meant to be seen onscreen by the audience, you have to use the scene description anyways.

It may seem like a very small detail, but it matters. Scene description sets the stage. Use it for those important details.

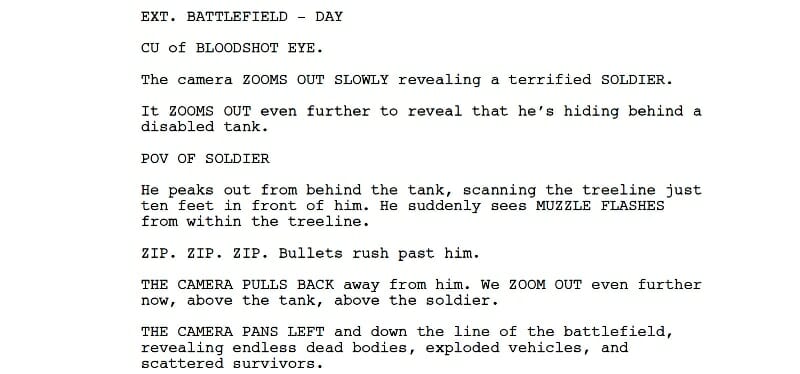

Too many screenwriters feel the need to direct the camera within their scene description.

They likely believe that writing a cinematic screenplay entails showcasing stylistic camera angles and movements, but nothing could be further from the truth.

For the reader, it’s very distracting. It often slows the read down to a halt as they try to interpret the camera directions.

Beyond that, the eventual director and cinematographer are going to do what they want anyway, so there’s no need to call for specific angles, movements, and shots.

At times, it’s okay to do so. But only if such directions — like a closeup or pan that reveals something — are partial to the story. Beyond that, it’s best to just give the reader the basic details and let their own imagination and visualization fill in the holes.

We know that you want to set the stage and create an atmosphere. Music does play a big part in the final cut of any film. However, screenwriters can often fall into unseens traps when they begin to dictate exactly what songs are to be played and heard during specific moments within the script.

First off, the screenwriter cannot dictate what songs will be available for the eventual filmmakers and studio. Soundtracks cost money. And most of the time, studios are signed to specific music labels. Or the budget of the film may not be enough to include that classic or current hit. Or the artist or label may not want to attach their song to your movie.

Secondly, what happens if the reader doesn’t know the song that you are referring to? Anytime that you’re referencing a specific song within a script, you’re telling the reader that this is partial to the story. If it’s not, it’s a waste of space, and you’re doing someone else’s job. If it is partial to the story, and they don’t know the song, there’s an instant disconnect.

It’s better to merely dictate the genre of the music that you feel should accompany the scene.

Instead of writing The House of the Rising Sun by The Animals plays, consider writing Classic 60s rock plays.

A common misconception is that a slugline is another name for the scene heading. Sluglines are instances within the scene description where you use CAPS to identify information that you want to call attention to.

![]()

Some writers overuse these. Others don’t use them at all.

Sluglines and action elements written in CAPS are effective ways to call attention to the surprising — or important — visuals within your scenes. There is no rule as far as how much or how little you should use them, but the best thing you can do as a screenwriter is use them only when necessary. Some scenes may call for more than others. Other scenes may not need them at all. Use your best discretion.

Yes, rules are meant to be broken. Understand that these are just guidelines to follow through a majority of your screenwriting. If you want to break or bend them every now and then, go for it. Just make sure that you do so few and far between.

Sometimes you need to write a longer and more detailed block of scene description.

Sometimes you need to group separate visual descriptions together in one block to save space or pair them up.

Sometimes you forget to delete that time, date, or specific location from your scene headings.

Sometimes you need to have a little camera direction to reveal something.

Sometimes you need to reference a specific song if it’s partial to the story.

But if you apply these five guidelines to help you write more effective scene description and better the read of your script, the reader will appreciate it. And those readers aren’t just interns and assistants. They are also managers, agents, development executives, producers, directors, and talent — the people that can make or break your career.

Ken Miyamoto has worked in the film industry for nearly two decades, most notably as a studio liaison for Sony Studios and then as a script reader and story analyst for Sony Pictures. Make sure to read his growing archive of posts at ScreenCraft for more inspiration.

He has many studio meetings under his belt as a produced screenwriter, meeting with the likes of Sony, Dreamworks, Universal, Disney, Warner Brothers, as well as many production and management companies. He has had a previous development deal with Lionsgate, as well as multiple writing assignments, including the produced miniseries Blackout, starring Anne Heche, Sean Patrick Flanery, Billy Zane, James Brolin, Haylie Duff, Brian Bloom, Eric La Salle, and Bruce Boxleitner. Follow Ken on Twitter @KenMovies

For all the latest from The Script Lab, be sure to follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.