By Ken Miyamoto from ScreenCraft · February 4, 2019

What goes into developing and writing a great spec script that becomes a calling card for the screenwriter, leading to meetings with agents, managers, development executives, and producers?

The calling card spec script is the one that gets screenwriters noticed within the industry. It is the coveted sample that works as a magical key, unlocking those seemingly impenetrable doors of agencies, management companies, studios, and production companies.

While every screenwriter should have a substantial collection of outstanding spec scripts — scripts written under speculation that they will sell — it’s usually one particular sample that breaks through and gets the writer noticed.

These types of scripts have different qualities that stand out from the rest. They exemplify the essential qualities of your cinematic storytelling arsenal. In short, they showcase what you’re capable of as a screenwriter.

But what makes for a compelling calling card spec script? What separates one from the other?

Learn how to write a screenplay in 5 weeks with this guide.

Here are some general guidelines that you can start with when deciding on what script you want to write next.

Hollywood reads hundreds of screenplays per month, thousands per year. The script market is a dense ocean of material, and most of it is either bad or bland.

For every hot trend making big bucks at the box office, there are dozens of copycats in the works at major studios and major production companies. And then there are a hundred more being written by eager novice screenwriters.

To stand out, you need a spec script that offers something new. If you can keep that reader turning the page — if not at first merely because what they are reading is different from the stack of scripts they’ve just read — you’re beating out most of your competitors. And you accomplish that by writing something different. Something nobody has read before.

It often starts with the concept, because Hollywood is all concept, concept, concept. The idea is what sells the project, what gets it made, and what puts butts into those comfortable recliner seats.

In 2015, Bubbles — written by Isaac Adamson — topped the industry’s Black List. Here’s the logline:

Pop star Michael Jackson adopts a baby chimp. Narrating his own story, Bubbles the Chimp details his life within The King of Pop’s inner circle through the scandals that later rocked Jackson’s life and eventually led to Bubbles’ release.

If that’s not something different, what is?

And the compelling story behind this hot spec script is that the industry went nuts over it. Everyone loved the script — agents, managers, development execs, and producers. It was unique. It was original.

There’s no answer to how to find those unique and original concepts. No screenwriting guru could have had the foresight to say, “Consider writing a Michael Jackson story told through the eyes of his pet chimp, Bubbles.”

You, the screenwriter, have to do that work. And you accomplish this by looking at what’s been done and conjuring concepts that haven’t been done.

And you can attempt to develop risks that may sound crazy and unconventional, as long as you apply great cinematic storytelling techniques, structures, and characterizations.

Writing some strange, weird story that is simply strange and weird to be strange and weird isn’t going to get you anywhere. It still has to be producible and attractive to not only Hollywood studios and production companies, but to audiences as well.

So go take some time to conjure those unique, original, and just plain different types of concepts to explore. If one of them pops out at you, with which you can apply great story, characters, and cinematic structure to, give it a shot. It may just become that calling card spec script you’ve been hoping for.

Download your favorite screenplays here for free

This is the most common mistake screenwriters make. They see a trend and write their own version of it. How many Pulp Fiction wannabes were there in 1995 and 1996? Plenty. How many Die Hard rip-offs were written in the nineties? Many.

Now, we do see Hollywood churn out some additional hits that are clearly “inspired” by these predecessors, but what novice screenwriters don’t understand is that’s primarily because the Hollywood power players can get those types of projects greenlit quickly.

When you’re an undiscovered screenwriter, you can’t move a project that fast. It takes you at least a few months to develop and write it. Then it takes upwards of a year or more to win a contest, competition, or fellowship or get it read through submission queries and networking. Then months of general meetings and calls follow. Then it would take at least a couple of months for any acquired representation to shop it further around Hollywood to find a buyer.

By the time your script gets to that stage, Hollywood has already beaten you to it, and the trend is dead.

Alien is a classic that everyone has seen. The same can be said for Predator, The Breakfast Club, The Thing, Goodfellas, The Sixth Sense, or any other iconic flick.

Most studio script readers can attest to the fact that so many screenwriters not only chase trends, but they also chase nostalgia. While nostalgia is hot right now in the industry (Stranger Things, It, and continual reboots and remakes), Hollywood is busy developing those properties and prospects. They’ve already beaten you to the punch, even if you aren’t aware of it.

Yes, this may sound like an oxymoron, but it’s true. Hollywood loves the familiar. But they do because that’s what audiences love as well.

However, once the familiar has been played out, the next best thing is a new take on what we’ve already seen.

The art behind finding a unique take on a familiar genre or subject is exploring where the original didn’t go. In the Eighties, we already had a plethora of movies with action heroes taking on bad guys. When Die Hard came along, we were offered the all-too-familiar concept of a good guy taking on bad guys, but the different take on that premise was that the hero was an average guy that showed emotion and felt pain.

John McClane wasn’t John Rambo from the Rambo franchise or Matrix from Commando.

He was an average guy that had tears of pain in his eyes when shot and tears of emotion in his eyes when sharing his feelings about how he failed his wife in their marriage.

Familiar is great, whether it be a hot trend or type of movie that everyone has seen. But since you’re not a Hollywood power player that can get a retread, reboot, or remake going, you have to be more creative and find different ways to find different takes of what has proven to be popular before.

Entourage gave us a peek into Hollywood A-List life. Ballers offers a similar look into the NFL.

Bull Durham gave us a look into minor league baseball through the player’s eyes while Moneyball showcased what it was like running a major league baseball team on a budget.

The original The Fast and the Furious took a classic action film that everyone had seen — Point Break — and offered a unique take on the concept of an FBI agent going undercover to find a band of thieves by applying a different world to it. Instead of the world of surfing, the undercover FBI agent character-type would be disappearing into the world of illegal street car racing.

A majority of the story and character beats are near identical to those found in Point Break, but the different world enticed Hollywood and audiences enough to want to see that updated take.

The world you feature can play an integral part in your spec script becoming a calling card. And it doesn’t even have to be accompanied by an already familiar concept, story, or genre-type.

If you have a story that delves into a world the cinema hasn’t featured, that may be enough to tip the scales in your favor. If you’ve worked in any specific industry or lived in any particular place and have an interesting inside perspective to offer, that may be enough if you’ve written it well.

If you yourself haven’t had that experience, but you’ve researched a specific world well enough to have it become the center of a compelling cinematic story, great.

Hollywood loves to develop features and television series that explore specific worlds. Audiences love to watch them because humans are a curious race. We love inside looks into worlds and places we don’t know.

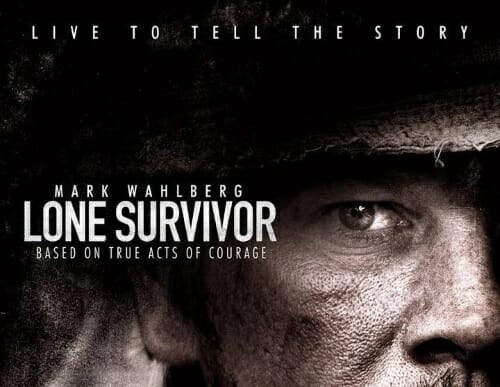

Whether it’s your story, someone you know, someone you’re related to, or something you’ve researched, true stories are always a hot commodity in the eyes of Hollywood.

If they haven’t been told before, you have that originality box checked. If they showcase a specific world that audiences don’t know, or at least an unfamiliar part of an otherwise familiar world (military, law enforcement, etc.), then you have that covered as well.

Screenplays based on — or inspired by — true stories are amazing calling card spec scripts.

Calling card spec scripts are more often than not written with a specific constrained structure and pacing. They’re page-turners, the coveted type of script that all script readers yearn to get their hands on.

It’s not just about short scenes and short scripts. Page-turners encompass a compelling concept, the brilliant and easy-to-visualize delivery of that concept, and the aesthetics of the script.

When a script is easy to read and compels you to keep turning to the next page — not out of obligation but because of a need to know what happens next — your script has a better chance of standing out.

In fact, some well-crafted page-turners with otherwise familiar concepts and characters have been known to rise up to the top of script stacks in agencies, management companies, studios, and production companies because they showcase outstanding cinematic writing alone.

Some key directives to writing a page-turner:

Having a script that is 120 pages or more isn’t the ideal page-turning experience. By page 75, readers want to see the story making its way to the climax. If another 50-60 pages are required to do that (instead of a more readable 25-30), you’re going to start losing people. Sure, if it’s well-written all the way through, that’s good. But we’re talking about page-turners specifically here, and how your spec scripts can stand out because of them.

Overall, there’s no specific formula for writing a calling card spec script. Lightning is difficult to capture in a bottle. But if you explore these above guidelines, you’ll hopefully have a reliable compass to help guide you towards that spec script that can become the coveted calling card you need to get noticed in today’s Hollywood.

Ken Miyamoto has worked in the film industry for nearly two decades, most notably as a studio liaison for Sony Studios and then as a script reader and story analyst for Sony Pictures. Make sure to read his growing archive of posts at ScreenCraft for more inspiration.

He has many studio meetings under his belt as a produced screenwriter, meeting with the likes of Sony, Dreamworks, Universal, Disney, Warner Brothers, as well as many production and management companies. He has had a previous development deal with Lionsgate, as well as multiple writing assignments, including the produced miniseries Blackout, starring Anne Heche, Sean Patrick Flanery, Billy Zane, James Brolin, Haylie Duff, Brian Bloom, Eric La Salle, and Bruce Boxleitner. Follow Ken on Twitter @KenMovies

For all the latest from The Script Lab, be sure to follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.