Sign up for the

TSL Newsletter

and get $50 off Final Draft 12

By Martin Keady · March 27, 2023

There’s nothing like great screenwriting debuts. The appearance of a wondrous new work of art creates a sense of wonder in the modern reader or viewer, akin to an inhabitant of the Middle Ages witnessing a meteor; there’s the same sensation of seeing something new and mysterious suddenly appear in the sky. It’s true of such momentous debuts as the First Impressionist Exhibition of 1874 and the 1967 release of The Velvet Underground and Nico, and it’s true of the stellar screenplays in this collection.

However, even great screenwriting debuts are rarely the first work that an artist creates. That was proven again recently by the posthumous release of Lou Reed Words & Music, May 1965, an early demo of his work, before he and John Cale “feedbacked” it up, in which the influence of Dylan is almost painfully obvious. Consequently, even these great screenwriting debuts often result from earlier, agonizing missteps before a switch is flicked, and somehow the right and unforgettable words start to flow.

Let’s dive into our curated list of ten of the greatest screenwriting debuts ever written in English.

Read More: The Greatest Directorial Debuts of All Time

It’s easy to forget that arguably the greatest film ever made was based on a debut screenplay, or at least the debut of a great screenwriting partnership, Herman J. Mankiewicz and Orson Welles. As David Fincher’s sublime Mank (2020) reminded us, Mankiewicz was a Hollywood veteran by the time Kane was made, but it required his collaborating with the much younger Welles for him to realize his long-held ambition of depicting the dark reality behind the American dream.

As Fincher and other Mankiewicz devotees argue, Mankiewicz was the Ur-creator of Kane. However, it was surely the interaction of both jaded genius (in the form of Mankiewicz) and youthful genius (in the form of Welles) that is the key to the screenplay and, indeed, the film’s success. On the one hand, the film enables us to delve into every aspect of Charles Foster Kane’s life and accomplishments. He started out as a destitute boy with only a sled to his name but grew to become an elderly man who wielded power over the world in a manner that even modern-day billionaires such as Elon Musk can only envision. Ultimately, Citizen Kane was the sole creation of the greatest screenwriting partnership in the history of Hollywood.

Read More: Citizen Kane: A Film of Mythological Proportions

Download the script!

If Citizen Kane was the high point of Golden Age Hollywood in terms of complex, powerful, and even mythical screenwriting, then Bonnie and Clyde was virtually the starting point of Hollywood’s Second Golden Age in the late 1960s and 1970s. Its writers were another revolutionary screenwriting team or partnership, David Newman and Robert Benton. They met while working together on Esquire in the early 1960s and channeled some of the iconoclasm of the best journalism and non-fiction of the age. It stood in stark contrast to the Hollywood of the time with its emphasis on big-budget (and often boring) musicals and channeled it into a screenplay about the couple who to this day remains America’s most iconic criminals, Bonnie and Clyde.

The film’s tagline summed up how it was a departure from so much of the American movie-making that had come before it: “They’re young…They’re in love…They kill people!” Such self-consciously controversial storytelling was the essence of the nouvelle vague (new wave) of French cinema that had emerged nearly a decade earlier with Godard, Truffaut et al, but Newman and Benton gave it a uniquely American twist. As with Mankiewicz and Welles before them, theirs was not a long-lasting partnership, and they certainly never wrote another script to match their astonishing debut. But with Bonnie and Clyde, they set American cinema and American culture in general on the blood-strewn path to The Godfather, Taxi Driver, and all the other tooled-up classics that followed it.

Read More: Bonnie and Clyde: A Transition

Download the script!

As William Goldman wrote in his great book about screenwriting, Adventures In The Screen Trade (1983), it wasn’t Taxi Driver that won Best Picture at the 1977 Oscars, nor even Network or All The President’s Men, in what was an unusually fine year for American film-making. Instead, it was Rocky, Sylvester Stallone’s epic tribute to the underdog, which he both wrote and starred in.

The story of the writing of Rocky is so remarkable that it is surely the next 1970s film, after The Godfather and (reportedly) Chinatown, to have a film made about its creation. By his own admission, Stallone faced financial ruin if he had continued solely as an actor. So, initially inspired by seeing Chuck Wepner, a complete underdog, taking The Greatest fighter of them all, Muhammad Ali, to 15 rounds (and flooring him in the process), he wrote a script about a similar underdog being granted a chance to win the World Heavyweight Championship.

In an age when UFC and mixed martial arts seem to have replaced boxing in the public sporting consciousness (especially among young people), it is important to recognize the historical significance of boxing and its impact on popular culture. It is now almost impossible to recollect how big the sport was in the 1970s when the unique Ali made it central to popular culture. Stallone brilliantly cashed in on boxing’s importance at the time and then had even more sense not just to cash in on the script itself, instead insisting that he himself had to play the title role before selling Rocky.

Read More: The Hero’s Journey Breakdown: Rocky

Download the script!

James Cameron continues to rule cinema, at least commercially, with the release of Avatar 2 and the forthcoming releases of Avatar 3, Avatar 4, and – doubtless – Avatar Ad Infinitum. It’s generally acknowledged that the success of the Avatar franchise isn’t largely due to the screenwriting, which was primarily done by Cameron himself. Instead, the exceptional visual effects that Cameron, a master of technology in filmmaking, creates are the major contributing factor. However, this is not the case for Cameron’s pivotal film, The Terminator, where screenwriting played a significant role in its success. Written with the film’s producer, Gale Anne Hurd, who he would later marry (and divorce), The Terminator is a great screenplay that was the basis for what is arguably Cameron’s only truly great film.

The Terminator was not Cameron’s directorial debut; that had been Piranha II: The Spawning (1982), one of the seemingly endless killer-fish films that swam or, more often, sank in the wake of JAWS. However, it was his screenwriting debut or at least co-screenwriting debut, and it provided the brilliant blueprint for his almost instantly mythical creation of a robot killer from the future sent to slay someone in the present.

Read More: The Hero’s Journey Breakdown: The Terminator

Download the script!

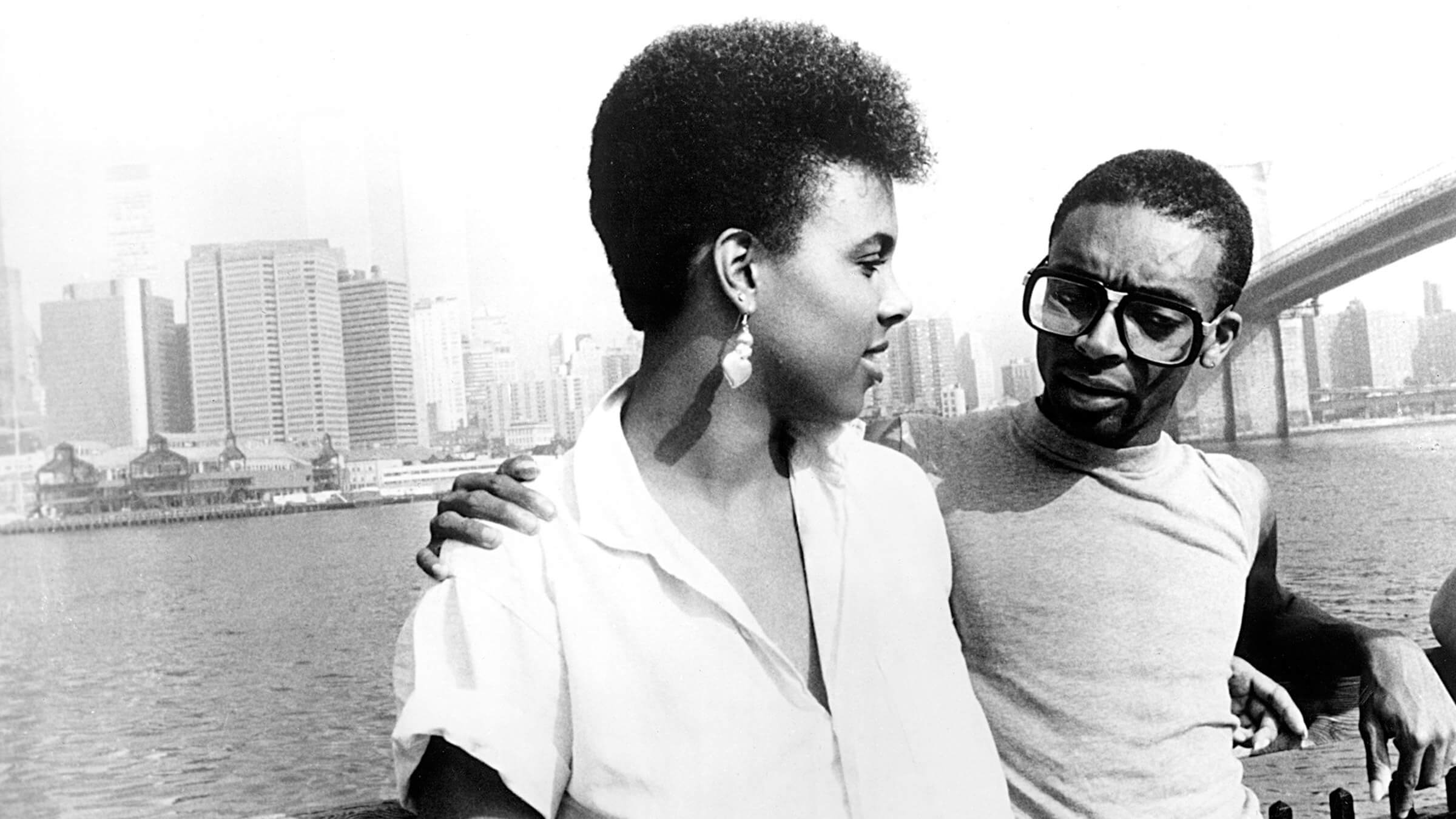

When Spike Lee released his debut film, She’s Gotta Have It; he was frequently described as “The Black Woody Allen.” That was not only because he wrote, directed, and starred in it but because the bespectacled character he played bore a superficial resemblance to Allen. However, She’s Gotta Have It soon made it obvious that such a comparison was utterly inaccurate. It was not only full of the black people who are usually so conspicuously absent from Woody Allen films, but it also focused on the sexual relations of a young woman and not those of a middle-aged man.

The heroine of She’s Gotta Have It is Nola Darling, whose surname was surely a nod to Darling (1965), the Julie Christie-starring British classic. However, whereas Christie’s model is very much the object of attention for various men, Nola Darling’s African-American graphic designer is nobody’s object but her own, as she wilfully and skilfully plays off against each other the three very different men in her life. Thus, She’s Gotta Have It was not only a landmark for black cinema but for black feminist cinema.

Read More: 5 Trademarks of a Spike Lee Script

Download the script!

An even more momentous landmark in women’s cinema was Thelma and Louise, the “feminist road movie” written by Callie Khouri. After nearly a century of mismatched men or, at best-mismatched couples hitting the highway together, Khouri stunningly inverted the genre by making her best buddies best female friends. The event that triggers their escape from their families and the authorities is not a minor offense such as robbery but rather the most intrusive and violating of crimes, specifically rape or at least an attempted rape.

Khouri, along with other writers on this list, such as the co-writing teams of Mankiewicz and Welles, as well as Benton and Newman, illustrates that crafting an exceptional debut screenplay can have its drawbacks. It can be a daunting task for a screenwriter to surpass or even equal the quality of their first work. That is not to suggest that Khouri has not been successful post-Thelma and Louise; she certainly has been, having written and produced, among others, the TV series Nashville and the Aretha Franklin biopic, Respect. But even those highly creditable works do not come close to matching Thelma and Louise. That was a genuine era-defining and genre-redefining classic.

Read More: 3 Screenwriting Tips from Thelma and Louise Screenwriter Callie Khouri

Download the script!

Of course, there are always exceptions to the rule; indeed, the most important rule might be that there is always an exception to the rule. If Callie Khouri and others could not quite match, let alone exceed, the brilliance of their screenwriting debut, Quentin Tarantino, arguably the greatest and most influential screenwriter of the last 30 years, certainly did. With Pulp Fiction (1994), his endlessly quotable epic about LA lowlife, and Jackie Brown (1997), his Elmore Leonard adaptation (which might be the best Elmore Leonard screen adaptation), he triumphantly built on his fantastic freshman effort. But it all began with Reservoir Dogs.

Perhaps more than any other script on this list, Reservoir Dogs exemplifies that even a great debut is rarely a complete one. As QT gleefully admits, he had written several scripts before Reservoir Dogs and even directed a low-budget film that he was too embarrassed to release. However, even if True Romance was the first script he completed and sold, Reservoir Dogs was always his favorite script-child, so he insisted on directing it, too.

Read More: The Defining Scripts of Tarantino

Download the script!

Much like Bonnie and Clyde and Citizen Kane before it, Reservoir Dogs revitalized American screenwriting (and indeed all screenwriting globally). At its worst, that effect was evident in the seemingly endless Dogs-alike screenplays and films that followed it. But at its best, it led to a new generation of young, hungry screenwriters writing directly, painfully, and often in a painfully funny way about their lives and dreams. And that includes the next two entrants on this list.

In many ways, Clerks was the anti-Reservoir Dogs in that its protagonists were not the small-time crooks that Tarantino wrote about but the employees at the video rental stores and other retail outlets that Smith and even Tarantino himself had worked in (most of which have now vanished). That absolute authenticity, or “lived experience” as it is often called now, is evident in Clerks, especially its humor, but not so much in all the Jay and Silent Bob spin-offs that inevitably followed.

Read More: The World Through Kevin Smith’s View Askewniverse

Download the script!

Even better than Clerks, however, is Swingers, Jon Favreau’s fabulous script about out-of-work (and nearly out-of-hope) actors in LA just before the turn of the millennium. Alongside Sideways (2004), Alexander Payne’s superb film about a writer and actor who are friends, it is the best of the numerous American cousins of Bruce Robinson’s immortal Withnail & I, which remains the best film ever written about actors and arguably the best film ever written full-stop.

Inconceivable as it may seem now that Favreau is “Happy” in seemingly every Marvel film ever made, at the time he wrote Swingers, he really was struggling, and that struggle is evident in the screenplay’s DNA. Swingers is almost as quotable as Withnail & I, with lines like “You’re so money!” immediately entering the wider culture. Structurally, it’s not quite as perfect as Withnail & I (the jaunt to “Vegas, Baby!” really should have come in the middle of the film rather than starting it). Otherwise, it is a stunningly good debut screenplay that will be read and quoted when the MCU has become a distant memory.

Download the script!

The best joke in Argo, Ben Affleck’s marvelous film about the unbelievably true story of how the CIA rescued Americans from the Iranian revolution by pretending to be Canadian filmmakers, is about the film’s title. Characters continually ask what “Argo” actually stands for, and eventually, Alan Arkin’s film producer (who co-operates with the fake filmmakers) declares, “Ah, go fuck yourself!” Well, in a similar vein, if you’re ever asked, “D’you know a really great debut screenplay?” you can simply reply, “Juno.”

Diablo Cody is the unforgettable pen name for Brook Maurio, and having invented such a memorable nom de plume writing a great screenplay was probably easy. Juno really is a great screenplay, telling the story of a teenage girl who becomes pregnant but decides that, rather than aborting the child or keeping it herself, she will give it away to a deserving pair of adoptive parents. Unfortunately for her, the adoptive father she chooses turns out to be more interested in her than in her unborn child. Achingly funny and unbearably moving in equal measure, Juno is that rarest of things – indeed, a thing rarer than a great debut screenplay. It is a teen movie for all ages.

Read More: Just Write: Diablo Cody’s Improbable and Unstoppable Rise

Download the script!