Sign up for the

TSL Newsletter

and get $50 off Final Draft 12

By Martin Keady · April 17, 2023

Stanley Kubrick movies make up one of the most unique and masterful bodies of work in cinematic history.

Although born and bred in New York City, one of America’s most revered directors, Stanley Kubrick, was a Brit at heart. According to The Guardian, Kubrick moved to England in 1961 after he had been hired by Kirk Douglas to replace another director on Spartacus. He lived in the UK until his death in 1999 and it’s currently home to his more than 400 boxes of personal archives – only just recently available to the public at University of the Arts London.

During his time in Britain, Kubrick effectively created his own artistic universe, one in which he enjoyed a degree of artistic autonomy unmatched by any other director anywhere, before or since. There, he could recreate the war rooms of the Cold War, prehistoric (indeed, pre-human) Africa, outer space and all the other “film-worlds” that he created, far from the interference of Hollywood, even as Hollywood studios continued to finance him.

Let’s take a look at some of the best Stanley Kubrick movies and the magnificent scripts that Kubrick made in Britain.

Scripts from this Article

The Cold War produced many classic films of the era. They include The Manchurian Candidate (1962), Fail Safe (1964) and Seven Days In May (also 1964). But foremost among them, for capturing the sheer, suicidal absurdity at the heart of the literally MAD (mutually assured destruction) doctrine of the Cold War, was Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove (or How I Learned To Stop Worrying And Love The Bomb).

As befits its subject matter – a rogue (read crazed) U.S. General accidentally starts World War III – Dr. Strangelove is the best, or blackest, black comedy ever made. The original novel that it was based on, Red Alert by Peter George, had been rather more serious, but with the inestimable assistance of Terry Southern, arguably the most satirical screenwriter ever, Kubrick turned it into a truly funny but also truly terrifying comedy about how the world might come to an end. Nearly 60 years on, the world has not ended – yet – but nor has the afterglow and influence of the first installment of Kubrick’s “Insanity” Trilogy, which may just be the greatest trilogy of films (however loosely linked they may be) ever made.

Out of all of the Stanley Kubrick movies, this one has to be one of the most recognizable.

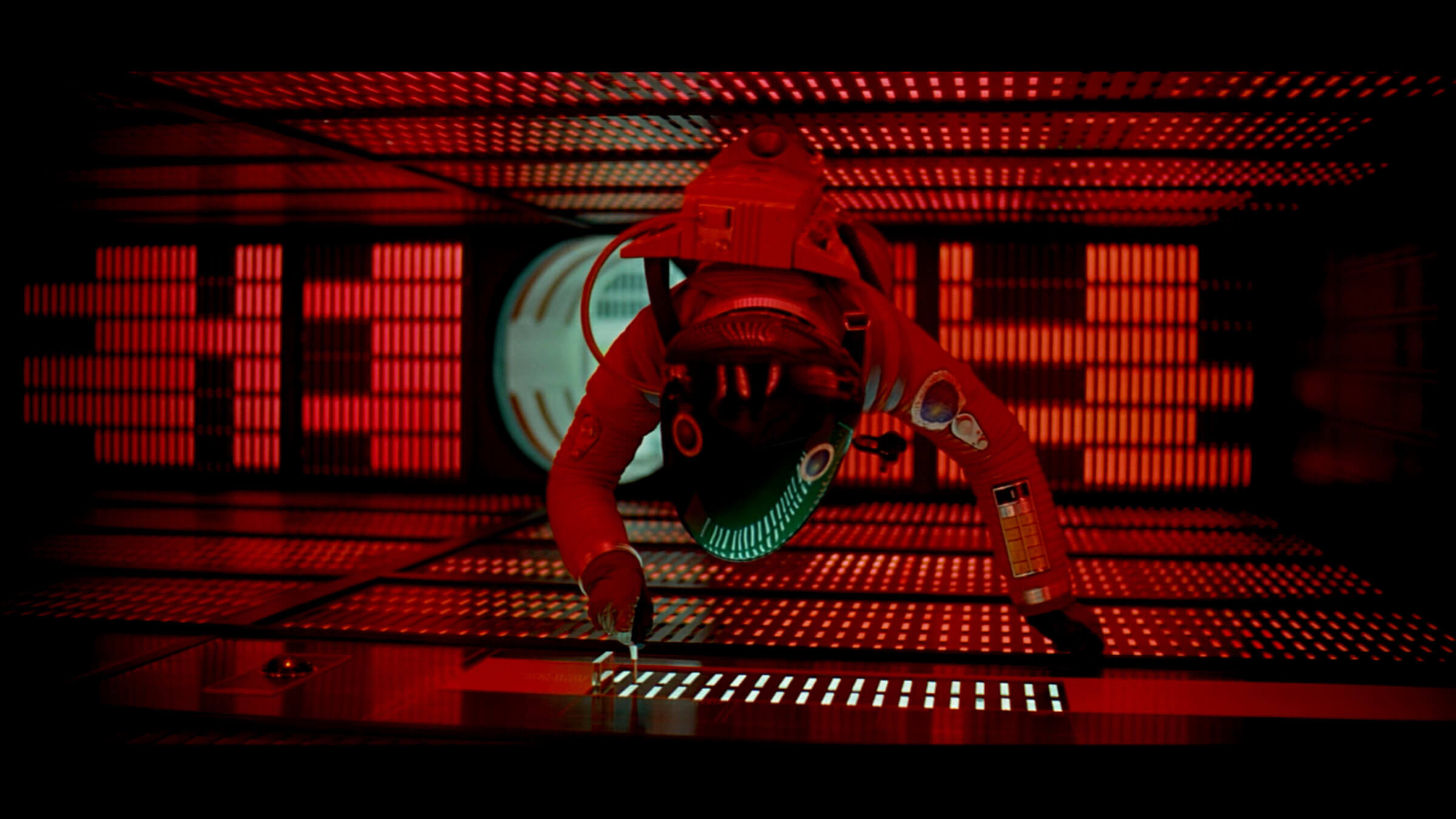

The success of Strangelove, Kubrick’s first film completely conceived and realized in Britain, gave him and MGM (the studio supporting him at the time) the courage and the patience to spend nearly half a decade making his next one. However, that courage and patience was triumphantly, indeed transcendentally, rewarded with 2001: A Space Odyssey. It is not only first among equals in Kubrick’s canon and the greatest science fiction film ever made but a strong contender, with the likes of Citizen Kane, Tokyo Story and Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, for the title of Sight & Sound’s Greatest Film Ever Made.

Kubrick wrote 2001 with Arthur C. Clarke, one of the greatest sci-fi writers of his age, with Clarke originally writing the long and complex story as a novel before he and Kubrick edited it into screenplay form. The result is almost a history of humanity and cinema. 2001 goes from the Silent Era (or at least the pre-linguistic utterances of our ancestors, the apes) to the Space Age (via the most famous cut in film history, between a bone-weapon being hurled into the air and a spinning space-ship) and even into the Psychedelic Era (with its final, literally dizzying “Stargate” sequence), as it attempts to divine the ultimate cause of humanity’s often completely contradictory behavior. And that is without even mentioning HAL, the super but psychotic computer that effectively prefigured all the dangers of AI that we are now starting to encounter in the 21st century. Some critics accuse 2001 of being dated, but the only thing that dates it is its title. Everything else is space lunchbox-fresh.

For more on the extraordinary backstory of A Clockwork Orange, see The Script Lab’s The Story Behind The Screenplay feature on it, which explains how Anthony Burgess’s original novel was born of the most painful private tragedy. But Kubrick’s film of the novel was the third and final part of his “Insanity” Trilogy, the three greatest Stanley Kubrick movies ever, in which he examined how humanity seems not so much to be conflicted as clinically mentally ill. In Strangelove, he nailed the collective, indeed global, madness of the age (a madness that tragically continues to this day); in 2001, he explored the possible (and possibly extra-terrestrial) root of that madness; and, finally, in A Clockwork Orange, he examined both the tension and the similarity between individual mental illness and state-sponsored insanity.

In showing how collective or even state crimes are ultimately far worse than individual criminal acts, the only film that has a comparable arc and overall effect to A Clockwork Orange is Krzysztof Kieślowski’s equally astonishing A Short Film About Killing (1988). That is arguably the greatest of Kieślowski’s Dekalog or “Ten Commandments Films,” which Kubrick himself adored. Just as Kieślowski first shows the seemingly cold-blooded murder of a taxi driver by an aimless and amoral drifter before showing the actually ice-blooded execution of the murderer by the state, so Kubrick first shows us (to quote the film’s tagline) “the adventures of a young man whose principal interests are rape, ultra-violence and Beethoven” before showing us the even more misguided, indeed evil, attempts of the state to control him.

Thus we come to the second set or trio of Stanley Kubrick movies the auteur made while living in Britain, beginning with Barry Lyndon, and there is no denying that there is a reduction in quality – or, if not quality, then sheer intensity. It was as if, having made his “Insanity” Trilogy, Kubrick eased off a little and contented himself with “merely” making three superb genre films, rather than the almost sui generis films that had preceded them.

Nonetheless, Barry Lyndon is one of the finest period dramas ever made and certainly the finest period drama ever shot, with the perfectionist-photographer Kubrick employing NASA to build lenses that allowed him to film by candle-light and thus effectively recreate the “look” of the late 18th century when Barry Lyndon is set. Arguably, only Visconti’s The Leopard (Il Gattopardo) (1963), one of the finest non-English language films ever made, matches or even exceeds Barry Lyndon for its iconoclastic approach to period filmmaking, showing all the blood and piss (and piss-pots) that exist behind the wigs and corsets. And it is also arguable that it was not until the BBC’s television adaptation of Hilary Mantel’s sublime Wolf Hall more than four decades later that the past was so beautifully illuminated as it was in Barry Lyndon.

Complete artistic control of the kind that Kubrick (and arguably only Kubrick in the entire history of cinema) enjoyed in Britain has its downside, which is a duality that Kubrick himself would surely have appreciated. Far away from the direct interference and commercial demands of Hollywood, Kubrick’s filmmaking in his latter years slowed to what would have once been called, before climate change, a glacial pace. Having made three masterpieces in the seven years between 1964 and 1971, the next three Stanley Kubrick movies, which are probably best described as near-masterpieces, took 16 years to make, with the gap between each one growing increasingly bigger.

Nevertheless, The Shining, like Barry Lyndon before it and Full Metal Jacket after it, is still a stunning film: the horror film for people (such as this author) who usually hate horror films. Stephen King, who wrote the original novel, famously hated it for straying too far from the source material, but Kubrick used that source material to create one of the best single-location films ever made. The Overlook Hotel is as intense and scary as the Pentagon War Room (in Strangelove) or the interiors of spaceships (in 2001). Awash with blood, and peopled by creepy twins and naked old ladies, The Shining was if nothing else a classic of set design, as Kubrick somehow recreated the snowy wastes of North America in the sleepy Home Counties of England.

Read More: The Shining: Shows What Adaptation Can Do

If it was impressive enough to recreate North America in England, it was even more impressive to recreate Vietnam in London’s Docklands, as Kubrick did with Full Metal Jacket. As ever with Kubrick, the film was a monument to his incredible eye (and ear and every other sense) for detail, as was also demonstrated in the unforgettable Kubrick exhibition at London’s Design Museum in 2019, which showed his meticulous attention to everything involved in making a film, from the first draft of a script to the final credits.

As for the writing of Full Metal Jacket, perhaps more than any other Kubrick film, and certainly more than any he made after The Insanity Trilogy, it foregrounds his fascination with Jungian dualism. It does so literally when the film’s ostensible hero, a soldier-journalist called Joker, tells a disbelieving general that his helmet, which has both a peace/anti-nuclear badge and the words “Born To Kill” on it, exhibits “Jungian Dualism”. And it does so metaphorically with its “two films in one” structure, showing first the brutal training of US marines and then the even more brutal war into which they are plunged.

The story of Kubrick in Britain ends with the only real misfire, or perhaps even outright failure, of his entire filmmaking career (at least since the early pair of films that he later disowned), Eyes Wide Shut, or Eyes Wide Shit, as it has commonly, but not completely unfairly, come to be known. And the failure of that film can be traced back to its source material, or rather Kubrick’s complete misuse of it.

Traumnovelle, or “Dream Novel”, was written by Arthur Schnitzler in 1926, in the Vienna of Freud and Kubrick’s beloved Jung, and Kubrick really should have set it there, when the story made sense, or at least a lot more sense than it did when transplanted to New York at the turn of the millennium. What was a story examining the mystery of human unconsciousness written at a time when that unconsciousness was first beginning to be explored became, in Kubrick’s final film, a fairly naff and even dull “erotic thriller,” in which Tom Cruise’s Doctor, rather than being titillated by the admission of his wife (played by Cruise’s wife at the time, Nicole Kidman) that she has fantasies about other men, is instead so enraged that he plunges headlong into a long night of the soul involving sex parties and murder victims.

As a consequence, Eyes Wide Shut is a completely unfitting epitaph for arguably the greatest ever cinematic adapter of great literature, because in Stanley Kubrick movies like Dr. Strangelove, A Clockwork Orange, Barry Lyndon, The Shining, Full Metal Jacket and even 2001 (which began life as a novel), Kubrick had proven that it was possible to make great films from great books and not just, as movie legend has it, from bad ones.

Read More: 94 Films Stanley Kubrick Absolutely Loved