Sign up for the

TSL Newsletter

and get $50 off Final Draft 12

By Martin Keady · March 3, 2015

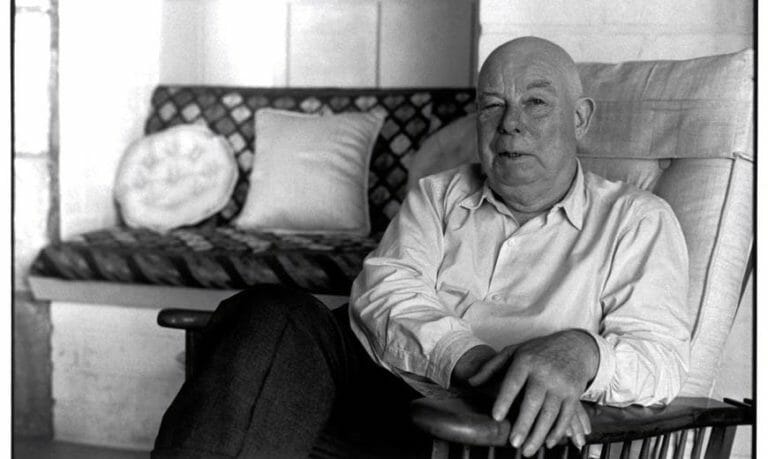

Has there ever been a father-son double act to rival that of Auguste and Jean Renoir? It is a rule of thumb that the children of great parents struggle to emulate them, but Jean Renoir arguably outdid his father, Auguste: the elder Renoir was one of the great Impressionist painters, but the younger is perhaps the greatest film director.

Jean Renoir’s legendary fair-mindedness, even-handedness and sheer humanity was summed up by the famous line that he himself spoke in one of his greatest films, La Règle du jeu (The Rules of the Game): “Everyone has his reasons.” His personal and artistic qualities may have come from being his famous father’s son. For one thing, he must have inherited Auguste’s fabulous vision (literally, his remarkable eyesight): although Jean chose to become a film-maker rather than an artist, cinema is still essentially a visual art and as a director he always employed the painterly skills of careful composition and framing that he must have learned at his father’s knee (or while modelling for one of the many pictures that Auguste painted of his young son). For another, he must have been aware from an early age of the essential struggle of existence: he would always have been aware of being “Auguste’s son” and the difficulty of trying to make a name for himself.

Ultimately, of course, Jean did make a name for himself, by making some of the greatest films ever made. Here are his Top 10.

10. Partie de Campagne (A Day in the Country) (1936)

Partie de Campagne is a short film (it is only 40 minutes long), but tells the story of an entire life. While on a visit to the countryside with her family, a young woman, Henriette, is seduced by a young man, Henri, while her fiancé is fishing with her father. What begins as a straightforward seduction, however, soon becomes mutual attraction, but Henriette has to rebuff Henri’s attempts to see her again, saying that her father would never allow her to return to the countryside alone. It is only years later, when she is unsatisfactorily married, that Henriette encounters Henri again by the same riverside. They recall their brief time together and realise that they have always been in love, but it is now too late to do anything about it.

Partie de Campagne is a wistful, beautiful, but ultimately tragic love story. It is also one of the finest examples of a film made by a great film-maker that was finished by another film-maker. (The Conversation, which Francis Ford Coppola filmed between the first two Godfather movies and which was finally completed by his sound editor, Walter Murch, is perhaps the finest example of this sub-genre.) Apparently, the original shoot was beset by problems, including constant changes of weather, and so Renoir abandoned the film. It was only finished and released more than a decade later, after Renoir had gained global fame with the likes of La Règle du jeu and La Grande Illusion, by Pierre Braunberger, a French producer who had worked with Renoir on some of his early films.

9. French Can Can (1954)

French Can Can is Renoir’s musical and while it may lack the majesty of his greatest works, it is an important film for two reasons. First, it marked his return to France after more than a decade in exile, following his departure to America in 1940 to escape the Nazis (for whom he was “Artistic Enemy Number One,” particularly after the release of La Règle du jeu). Secondly, it is something of a love-letter to his father and the milieu in which he gained fame: Paris at the end of the 19th century. Shot in glorious Technicolor, contemporary critics, such as a young Francois Truffaut, said that the film reminded them of the works of Degas and, yes, Papa Renoir himself.

For French Can Can, Renoir was also reunited with his great leading man (the De Niro to his Scorsese, or the Mifune to his Kurosawa), Jean Gabin. Gabin plays a café-owner who, facing bankruptcy, resorts to hiring can-can dancers to change, and ultimately, make his fortune.

8. The Golden Coach (1952)

The Golden Coach is the story of a ménage-a-quatre, as a young European actress, Camilla (played by the striking Italian star, Anna Magnani), is pursued in 18th century Peru by three men: the local viceroy, or governor; a torero, or bullfighter; and a soldier. The viceroy purchases the titular vehicle as a gift for Camilla, but in doing so provokes the ire of her other pursuers. The matter is only resolved when Anna realises that, as a true actress, she cannot sacrifice her career (indeed, her entire identity) for love, and gives the coach to the local church, which plans to use it to transport holy sacraments to those who are dying (truly making it a “golden coach”).

In its subject matter, The Golden Coach inevitably invites comparison with an earlier French masterpiece, Marcel Carné’s Les Enfants du Paradis (Children of Paradise), which was released at the end of WWII and which also told the story of a beautiful theatre actress pursued by three very different men. However, it also established a cinematic genre, that of the “Europeans in South America” movie (even if the film itself was shot at the Cinecittà studio in Rome), which has included such masterpieces as Werner Herzog’s Aguirre: Wrath of God and Fitzcarraldo, Roland Joffé’s The Mission and Dennis Hopper’s The Last Movie.

7. Le Crime de Monsieur Lange (The Crime of Monsieur Lange) (1936)

Renoir virtually defined French cinema in the 1930s, just as Godard and Truffaut and the other “new wave” film-makers did three decades later; like all great film-makers, indeed like all great artists, he first reflected his time and then captured it for eternity. Le Crime de Monsieur Lange is a classic example of that, embodying the socialist idealism of the Popular Front Government that briefly held power in France in the second half of the decade.

The titular hero is a Walter Mitty-type character (indeed, he predates James Thurber’s invention of Walter Mitty by three years) – a lowly clerk who dreams of being a successful writer. His chance comes when the head of the publishing company he works for disappears (having faked his own death to claim the insurance money). In desperation, Lange and his fellow workers first form a co-operative to keep the business going, then make the business a success by publishing Lange’s cowboy stories. However, when the head of the company reappears (to reclaim control of the company, which is now highly profitable), Lange has to enact one of his own cowboy stories, by shooting dead the “bad guy” and then fleeing from the “sheriff” (the police) with the girl he has fallen in love with.

Lange is particularly interesting in terms of its structure. The film actually opens near the end of the story, with Lange and his beloved seeking refuge in a hotel, only to be recognised by some of the guests. In desperation, Lange’s girlfriend tells the guest (and, of course, the viewer) their story, to try to elicit their sympathy. Like all storytellers from Scheherazade and her Arabian nights onwards, she is literally telling a story to save her life, and that of her beloved. It is an invaluable exercise for all screenwriters and directors to imagine that they too are literally telling a story to save their life: we must captivate or die.

6. Diary of a Chambermaid (1946)

Diary of a Chambermaid is one of Renoir’s finest English-language movies, made while he was in “exile” in America, but like much of his work it is based on a famous French novel (by Octave Mirbeau) that was later adapted for the stage. It is a classic “stranger invader” movie, like Pasolini’s Theorem, in which the arrival of a young female servant, played by the beautiful and boisterous Paulette Goddard, upsets the established order of an upper-class household (and the neighbouring households), as one by one the male occupants of the household (and some of their male neighbours) fall in love with her.

Diary of a Chambermaid was remade nearly 20 years later by Luis Buñuel, with Jeanne Moreau as his Chambermaid. Both films are fascinating, and demand to be “compared and contrasted”: Buñuel’s Chambermaid, as befits the period in which it is made (the mid-1960s), is darker, dirtier and more explicit; Renoir’s, typically, is more controlled, more chaste and more suggestive. Seeing them both is a remarkable illustration of how the same subject matter can be transformed by two very different directors: one, the great surrealist, who deplored the absurdity of bourgeois convention and upper-class domination; the other, the great humanist, who never forgot that, however absurd or even surreal a social setting, at its heart were real, feeling human beings.

5. The River (Le Fleuve) (1951)

Renoir returned to the riverside (the setting of Partie de Campagne) for this late classic. However, it is a very different river that he returns to: instead of the gentle, tranquil waters that flow through the French countryside, The River in this film is one of the world’s great rivers, the mighty Ganges, whose epic swirl and sweep is the backdrop to, and symbol of, the powerful emotions that envelop one expatriate family.

The River is an adaptation of the autobiographical novel by the great English writer, Rumer Godden (another of whose India-set novels, Black Narcissus, was made into another great film, by Powell and Pressburger). As so often with Renoir, it is a love story, specifically a love story tinged with tragedy, as a young girl belatedly realises that the man she has fallen in love with is actually in love with her best friend.

The River was one of the first major Western movies to be made in India (Black Narcissus, shot some four years earlier, was set in the Himalayas but largely filmed at Pinewood Studios). As such, it was one of the first films to open up the newly-independent Subcontinent to Western audiences, especially as it was one of the finest of the early Technicolor movies. Incidentally, it also had a profound impact on Indian cinema itself, as the greatest Indian director, Satyajit Ray, met Renoir while he was filming The River and was ultimately inspired to become a film-maker himself. It is a story worthy of a movie, as the great European humanist filmmaker metaphorically passed the torch to the great Indian humanist filmmaker, who in so many ways became his spiritual successor.

4. La Bête Humaine (The Human Beast) (1938)

In many ways, Renoir’s La Bête Humaine was a precursor to Claude Chabrol’s 1970 classic, Le Boucher (The Butcher): both films tell the story of a seemingly ordinary man who is driven by fate (and genetic inheritance) to commit a terrible crime. In La Bête Humaine, Jean Gabin plays a railway engineer, Lantier, who suffers dreadful, violent convulsions, apparently as a result of his father’s alcoholism. His condition makes his job difficult enough, but things get much worse when he witnesses a murder on the train, as one of his colleagues kills a man who he believes had taken advantage of his wife when she was a young woman. Because Lantier is himself in love with his colleague’s wife, he does not tell the police the identity of the murderer, but when Lantier and the wife begin an affair she asks him to kill her husband, so that they can be together permanently. Lantier has to conquer his demons (his seizures) to carry out the murder, in what is almost a proto-film noir, which, along with Hitchcock’s The Lady Vanishes (made in the same year), is also one of the first great “train-murder movies,” foreshadowing other classics of the genre such as Double Indemnity and even Strangers on a Train.

3. Boudu Saved from Drowning (Boudu Sauvé des Eaux) (1932)

Boudu was Renoir’s first true classic, made after nearly a decade as a director (it is hard to imagine any director, even as great a director as Renoir, being given so long today to make their first masterpiece). It is a fable, almost a fairytale, about a homeless man, or tramp, who is supposedly “saved” from drowning by a bourgeois book-seller who, feeling himself responsible for the man he has saved, takes him into his home, with predictably unpredictable consequences. As in Diary of a Chambermaid, the arrival of a lively, unconventional newcomer turns things upside down and, again as in Chambermaid, Boudu finds himself the object of affection for other members of the household, notably the book-seller’s wife.

It is the ending of Boudu that seals its classic status. Having miraculously won a fortune on the lottery, Boudu is effectively forced into conformity and an arranged marriage with one of the book-seller’s servants. At the last, however, he is unable to conform and returns to the river (so often the physical and spiritual setting of Renoir’s films) and the vagrant lifestyle that he had supposedly been rescued from in the first place.

2. La Règle du jeu (The Rules of the Game) (1939)

And so we come to the Top Two. In fact, the more of these cinematic “Top 10s” that I write, the more instructive I think it might be just to have a ‘Top Two’ for the greatest directors, reflecting the absolute pinnacle (or pinnacles) of their work. It would allow the inclusion of directors who may have only made a handful of films, for example Bill Forsyth, whose Gregory’s Girl and Local Hero, are a “Top Two” to match those of far more prolific directors.

For Renoir, whatever the merits of his other works, including Boudu and The River, the Top Two are undoubtedly La Règle du jeu and La Grande Illusion, and they are a twin salvo to match that of any other director. That is partly because they are so historically and cinematically important: made between the two great (and terrible) wars of the 20th century, La Règle du jeu literally foreshadows World War Two, while La Grande Illusion looks back at, and exposes, the folly of World War One.

The story of the making of La Règle du jeu is almost as extraordinary as the film itself. It was made in 1939, at the height of Renoir’s fame and success but also at the very outbreak of war. Ostensibly the story of a country-house party and the romantic entanglements of its varied guests, from a famous aviator to a humble gamekeeper, it is actually about the end of the old France, indeed the old Europe – in fact, the whole “old world” that had been nearly destroyed by World War One and that would finally be finished off by World War Two.

The plot of the film uncannily echoes the story of the period between the wars, as the various characters initially seem to be engaged in nothing more serious or sinister than what would today be called “partying” (mirroring the initial period of optimism and economic growth that followed the end of World War One) before tragedy, inevitably, ensues (prefiguring by just a few months the absolute tragedy of World War Two).

Renoir himself appears in the film (he acted in a few of his own movies) and his is one of the great performances, if not the greatest performance, by a director in his own movie: the likes of Erich Von Stroheim (in several movies, notably Sunset Boulevard and Renoir’s own La Grande Illusion) and, latterly, Sydney Pollack (particularly in Husbands and Wives and Michael Clayton), may have given greater performances, but in other directors’ movies. As David Thomson points out in his brilliant entry/essay on Renoir in his A Biographical Dictionary of Film, it is as if Renoir is showing that he, too, just like everyone else, is complicit in the unfolding tragedy that the film shows, and the greater, global tragedy that it foreshadows.

1. La Grande Illusion (Grand Illusion) (1937)

I would have absolutely no quarrel with anyone who selected La Règle du jeu as Renoir’s finest (his Number One). I choose La Grande Illusion for personal reasons: first, because it was the first Renoir film I ever saw (in cinema, as in love, there’s no time like the first time); and secondly, because of one scene (or, more accurately, sequence) near the end.

Two escaped French prisoners of war take shelter in a German farmhouse. When the “farmer” discovers them, it seems the game is up, but they survive, because the “farmer” is actually a woman, running the farm in her husband’s absence, and, even more importantly, she herself is a war widow: in fact, in addition to losing her husband to the war, she has also lost her three brothers.

What follows is still, for me, one of the most magical sequences in all of cinema. One of the PoWs, played by Jean Gabin, finds himself falling in love with the widow who has saved their lives; indeed, she saves them again when she refuses to turn them over to a passing German patrol. That clinches it for Gabin, who professes his love for the woman, not with any conventional declaration but by trying to learn a few words of German – the language of his enemy – including, “Lotte ab blauen augen” (“Lotte”, the woman’s daughter, “has blue eyes”). Tragically, his sense of duty and patriotism means that he has to return to the battlefield, but he promises the woman and her daughter that he will return to them after the war. We never know whether he does or not, but at least there is a chance: he and his fellow escapee manage to evade another German patrol and make it across the border to Switzerland.

That sequence, like the whole film, is classic Renoir: even-handed in its depiction of the two opposing sides (“Everybody has his reasons”); beautifully shot (even in black and white, Lotte’s eyes seem to glow bright blue); and ultimately, even in the midst of apparent hopelessness, hopeful.