By Martin Keady · August 17, 2023

There is a terrible irony in trying to determine exactly when the first movie camera was invented, namely that it would probably require the pre-existence of movie cameras to prove conclusively who invented them (and when). Instead, their precise origin remains so shrouded in mystery that, as the BBC’s Science Focus magazine put it when it recently tried to determine their origin, it is “a story worthy of Hollywood.” Indeed, it has all the ingredients of a great thriller, with competing claims from competing inventors, the unexplained disappearance of one of them, and even accusations of murder.

Read More: What Was the First Movie Ever Made

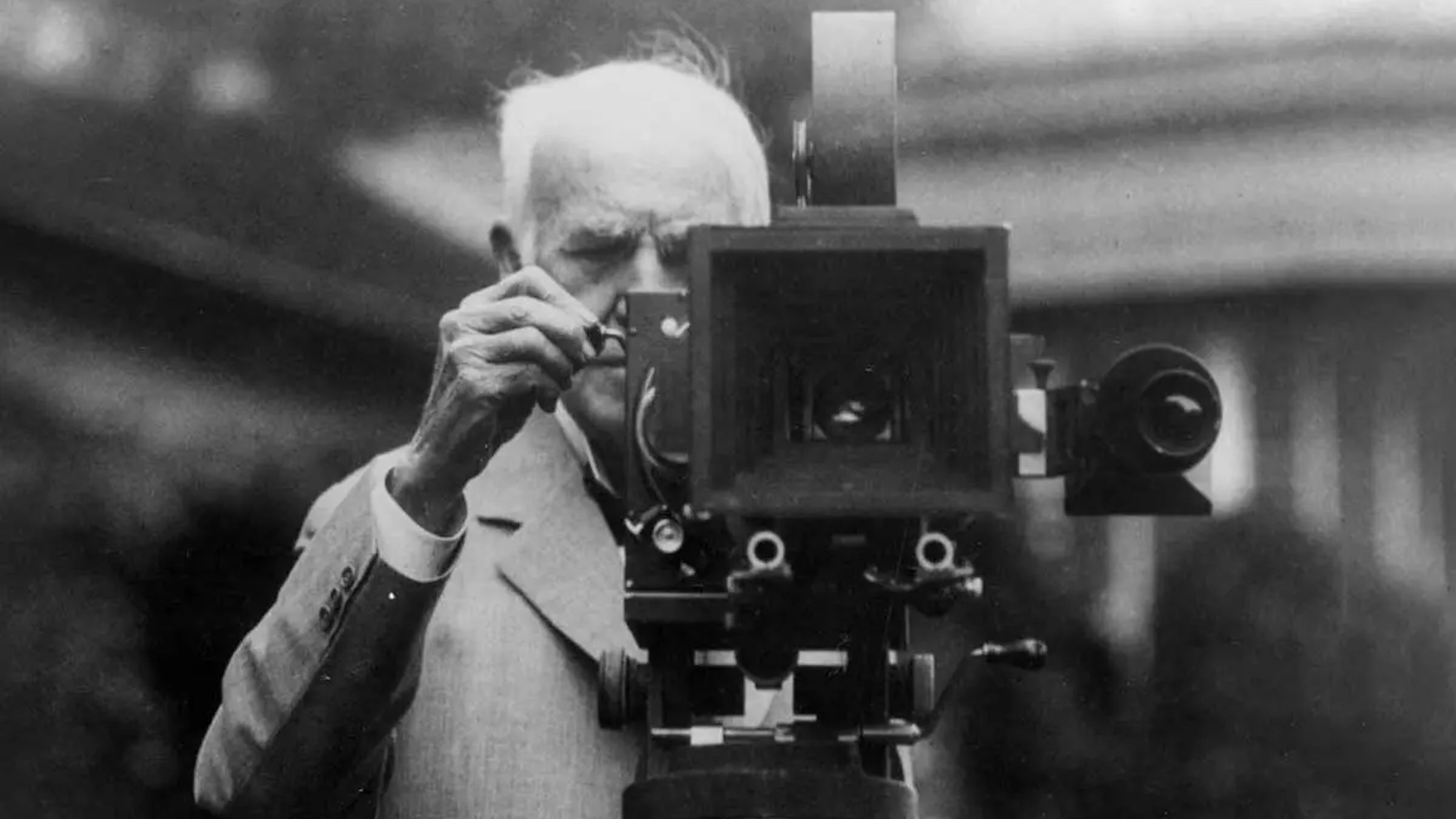

Thomas Edison 1847-1931 and George Eastman 1854-1932 standing with motion picture camera ca. 1925

On the surface, the answer should be relatively easy, because it would appear to be the Kinetograph, the rather primitive motion picture camera that Thomas Edison, the great American inventor of the light bulb and the phonograph (an early form of the gramophone, or record player), among many other things, and William Dickson, his British assistant, invented in 1890 and officially patented soon afterward at the U.S. Patent Office.

However, the key word there is “patented,” which is not the same as “invented.” In fact, the more one learns about Edison the more one is tempted to call him not a great inventor but a great patenter. He was undeniably brilliant and literally full of ideas, but he had so many that he could never fully realize them himself. Instead, even relatively early on in his career, he began to employ assistants, like Dickson, to help him to develop his ideas and, crucially, patented them as soon as he could, sometimes even before the actual inventions were fully complete, in order to secure their exclusive commercial usage.

That was where the real genius of Edison arguably lay. He pioneered mass production of objects that he or his team of assistants had invented and patented in a way that none of his other competitors at the time, both in the U.S. and Europe, did. It was either because they could not afford to or because they did not appreciate, as Edison always did, the commercial possibilities of new inventions.

In addition, Edison had a particularly serious competitor in England, who may have made the crucial technological breakthrough required to create the first movie camera before he did. That man was the enigmatic if not downright mysterious Louis Le Prince, a Frenchman who had emigrated to England’s industrial north in order to try and realize his own ideas about technological progress, particularly in the capture of moving images.

Now, more than a hundred years on, it is increasingly being accepted that it was Le Prince and not Edison who invented the first movie camera because he used it to shoot what is almost certainly the first ever “movie” (in the sense of moving pictures linked together), even if it only lasted for about two seconds.

That movie was what is known today, even though Le Prince himself did not formally title it, as “Roundhay Garden Scene” and it was shot in Leeds in 1888. So seemingly inconsequential is it that if it were shot today it would probably be dismissed as a “pocket dial” or “pocket film,” i.e. an accidental capturing of a few apparently random images. But because it was actually filmed exactly 125 years ago, it is almost certainly the original or Ur-movie or film, however brief it is.

Read More: A Brief History of Screenwriting

In effect, “Roundhay Garden Scene” only shows the very start of a movie or even just a movie scene as we would understand it today. Le Prince filmed his adult son Adolphe and another unidentified man, plus two unidentified women, literally just leaving a country house in the Roundhay area of Leeds to set off on a walk together. And that’s it. The scene, or “movie,” ends there and so does the film, which almost starts to distort.

Nevertheless, these are formative steps. They are also exaggerated ones. Adolphe, being probably the first person ever to be filmed after earlier and very primitive proto-movies about animals, such as Eadweard Muybridge’s famous The Horse In Motion in 1878, literally seems to be the first person ever to “play up” for the camera, swinging his arms almost like an orangutan in a suit as he sets off. But they are probably the first ever steps that cinema took on its century-long and globe-spanning journey to the point we are at now, where, with all due apologies to Shakespeare, all the world’s a screen rather than a stage.

Read More: The History of the Screenplay

In most official records of cinema, including Wikipedia and other online sources, it is Edison and not Le Prince who is generally credited with inventing the movie camera. In large part, that is because Edison was the first to name, patent and then mass-produce a movie camera, with his (and Dickson’s) Kinetoscope. But there is another far more fascinating reason, which is Le Prince’s extraordinarily untimely and incredibly mysterious disappearance at almost his exact moment of triumph.

That story, or rather mystery, has really been brought to light in the last decade by another Leeds-based film-maker, David Nicholas Wilkinson, operating over a century after Le Prince but determined to prove that Leeds and not West Orange, New Jersey, where Edison’s industrial operation (the first of its kind in the world), was based, is the birthplace of the movie camera.

The First Film (2015)

Wilkinson made a remarkable documentary in 2015 called The First Film, whose subtitle sums up its appeal for any cineaste: “The greatest mystery in film history.” At the heart of that mystery is the fact (one of the few facts in a space that is now necessarily full of conjecture) that Le Prince had planned to travel to New York to unveil his new movie camera to America, the world and, presumably, Edison. But he never got there.

Le Prince had returned to his native France, with the intention of taking the boat from there to America. But in a real-life twist worthy of a great Hitchcock thriller, he boarded the train in Dijon to go to Paris but never arrived. Neither he nor any of his belongings, which are likely to have included at least some of the material that he had hoped to present to the public in America, disappeared and have never been found.

Naturally, Le Prince’s wife and family, including his son Adolphe, the “star” of his first film, were horrified when they learned that he had never reached Paris. His wife immediately and instinctively suspected that he had been the victim of foul play, presumably from one of his competitors in the race to develop and, crucially, announce to the world the first movie camera. In the century since, there have even been allegations that “Le Prince” of cinema was somehow taken out by the man who hoped to become The King of cinema, Thomas Edison, or by agents in France working on his behalf.

Over a century and a quarter on, and despite the diligent detective work of David Nicholas Wilkinson and others, there is no definitive answer and it is highly unlikely now that there ever will be. However, if somehow some of Le Prince’s personal belongings should ever be found, they might just provide the vital evidence to solve this extraordinary cinematic mystery – indeed, the original cinematic mystery.

The Lumiere Cinematographe, introduced in 1895.

Like all the best mysteries or thrillers, the story does not end there, because there was a final act, or postscript, to the story in which both Edison and Le Prince lost out in their quest to create and then mass-produce the first movie camera. That was because for all the transatlantic cinematic arms race between the truly industrialized Edison and the essentially lone individual Le Prince, it was someone else entirely, or more precisely two people, who really developed the first really successful movie camera.

Those two people were the Lumière brothers, Auguste and Louis, who, with their assistant (or equivalent of William Dickson), Charles Moisson, made the vital technological breakthrough that sealed film’s future as the dominant medium not only of the late 19th century but of most of the 20th century. That was to shift from the paper film that both Edison and Le Prince had used to record their first moving images to celluloid film, which they purchased from America and then adapted for their own particular needs and which was far better at retaining sharp, clear moving images than paper film.

Auguste and Louis Lumière

In the same year (1894), Kazimierz Prószyński, a Polish inventor who is probably even less well-known than Le Prince, invented the Pleograph, which combined both a camera and a projector, which the Lumières eventually capitalized on and staged the first-ever public screening of a film in Paris in 1895, the date that is now almost universally regarded as the true birth of cinema, as evidenced by the 100th-anniversary celebrations around the world in 1995.

In truth, as with most inventions both in the Victorian era and now, it was something of a group effort, with Edison, the Lumières, and Prószyński all benefiting from each other’s work to make mass movie-making and, crucially, mass movie screening, which for so long had been dreamed of (arguably, ever since the first caveman formed shapes with his hands to project shadows onto cave walls) was finally a reality.

But for all their own inestimable inputs, the potentially pivotal role of Louis Le Prince should never be forgotten. And if nothing else, the remarkable true story of his still-unexplained disappearance invested the new medium of cinema with an air of mystery, intrigue, and even danger that it has retained ever since.