By Martin Keady · August 21, 2023

His surname sounded like the name for a movie theatre, so it was entirely fitting that Sidney Lumet should become a master of cinema. For exactly half a century, from 12 Angry Men (1957) to Before The Devil Knows You’re Dead (2007), Lumet was a truly great director, filming scripts by some of the greatest American playwrights and screenwriters of the late 20th century, including Paddy Chayefsky and David Mamet, as well as being a sufficiently fine screenwriter in his own right to secure an Oscar nomination for Best Adapted Screenplay for Prince of the City (1981).

A French film festival that could have been named in Lumet’s honor – the Lumière film festival in Lyon – ran a retrospective on him in 2022 and the program notes neatly summed up Lumet’s unique position in the history of American cinema by arguing that he was at the “crossroads” of the old-style studio Hollywood and the new-style New Hollywood of the 1970s. No other American director straddled both of those worlds.

This collection of Sidney Lumet movies, spanning his entire career as a film director, is the perfect introduction to Lumet’s cinematic world because they crystallize so many of his key concerns. They are almost all set in New York and concern an impassioned, even enraged, individual or group of individuals raging against the injustice that is meted out on them by an uncaring system.

Here they are, in chronological order: some of the brightest Sidney Lumet movies in his glittering career.

Scripts from this Article

It is arguable that Sidney Lumet is the most underrated great American film director there is. He may not have had the signature style or subject matter of a Kubrick or a Scorsese, but he had the versatility and sheer commitment to excellence of a Curtiz or a Spielberg. And that is perfectly demonstrated by 12 Angry Men, his debut film, which more than 60 years on remains one of the greatest directorial debuts.

12 Angry Men was based on a teleplay of the same name by Reginald Rose, which itself was based on Rose’s original play. In truth, such was the core strength of Rose’s central idea – a drama about a jury of 12 men deciding the fate of a teenager accused of murder – that it required relatively little adaptation. Nevertheless, for the movie version, Lumet constructed a beautifully intimate film, full of close-ups of the men’s faces, which is arguably the greatest single-location film ever made.

12 Angry Men (1957)

Rose’s brilliance as a writer was to show, in all the different media his story was made for, how one man could shift the opinions of 11 other men (or at least the overwhelming majority of them) by diligently soliciting the truth, rather than just relying on rumor, hearsay and circumstantial evidence. For the film version, Lumet elicited a career-highlight performance from Henry Fonda, who also co-produced the film, as the hold-out juror, cementing Fonda’s image and reputation as Hollywood’s go-to “good guy,” which Fonda would continue to trade on until Sergio Leone exploded that image by making him the worst of villains in Once Upon A Time In The West (1968).

Read More: 5 Plot Points of 12 Angry Men

Emboldened by the enormous critical and commercial success of 12 Angry Men, Lumet fully committed to filmmaking after earlier working in theatre and television and duly embarked on an extraordinary directing career. Over the next 15 years or so, he made a succession of superb films, including The Pawnbroker (1964), the first major American film to examine the Holocaust from the viewpoint of a Holocaust survivor; Fail Safe (also 1964), one of the finest Cold War thrillers of them all; The Hill (1965), a British film about a WW2 military prison camp that provided Sean Connery with probably his best ever non-Bond role; and The Offence (1973), in which Connery played a policeman who kills a suspected pedophile while interrogating him. Indeed, it would be possible to assemble an entirely different Script Collection of Lumet films from this period.

However, in the same year that the astonishingly prolific Lumet made The Offence, he also made the film that returned him to the template that 12 Angry Men had provided: a story about a lone New Yorker going up against a group of other New Yorkers, fighting seemingly impossible odds but supremely motivated by the justness of his cause. However, whereas Henry Fonda’s Juror 8 only had 11 other jurors to contend with, Al Pacino’s Frank Serpico was an honest cop fighting an entire police department riddled with corruption.

Serpico (1973)

Serpico was based on the biography written by Peter Maas, one of the finest American non-fiction writers of the late 1960s and 1970s, who had first found fame with The Valachi Papers (1968), a biography of Joe Valachi, the first Mafiosi ever to testify publicly against the Mafia. Serpico was remarkably similar, relating the story of an underling as he turned against his bosses, only this time it was the police who were being exposed and not the criminals. And as he had with Henry Fonda in 12 Angry Men, Lumet drew from Pacino a superbly subtle performance, exemplified by the cool insouciance with which he turns down a puff on a joint at a party before explaining to the astonished partygoers that he is actually a policeman. Pacino’s Serpico had far bigger fish to catch than a few errant stoners and he eventually caught them, albeit at enormous cost to his own career.

Read More: The Top 10 Best Al Pacino Films

Serpico was such a success that although he was much older than the “Movie Brats” (Coppola, Friedkin, Scorsese et al) who were taking over Hollywood, Lumet found himself grouped with them as a director of material that had previously been considered undeserving or even unworthy of being filmed, including stories about the Mafia, corrupt cops and exorcists. So, having made one of the last great studio-era pictures in 12 Angry Men before following it up with a mixture of high-profile Hollywood films and lower-profile but even higher-quality British films, Lumet virtually embarked on a second directorial career in the rest of the 1970s.

Pacino had clearly enjoyed working with Lumet so much that he worked with him again on a sort of loose “sequel” to Serpico, at least in terms of its controversial subject matter. That was Dog Day Afternoon, a heist film in which the heisters were a pair of what would previously have been called “degenerates”: two homosexuals (one married, one unmarried) who rob a bank in order to raise the money for one of them to have a sex change. Of course, the heist goes wrong, the robbers and several bank staff and customers are trapped with them in the bank, and we are back in a claustrophobically intense world (and single-location set) that is remarkably similar to the almost equally enclosed world of 12 Angry Men.

Dog Day Afternoon (1975)

Dog Day Afternoon was based on a Life magazine article about the real-life bank robbery by this unlikeliest of pairings, called “The Boys In The Bank.” Although Lumet changed the title to Dog Day Afternoon, which he felt was more evocative of the extreme heat and humidity of the New York summer’s day on which the action takes place, he otherwise largely stuck to the true events depicted in it. (His best films always had the feeling of being ultra-realistic, like true stories literally unfolding for the first time on the screen.) And for his pair of robbers, he put Pacino together with John Cazale, his fictional brother Fredo in The Godfather, and the two excelled, especially in the film’s still-shocking ending.

Lumet completed his incredible 1970s trilogy of masterpieces (during the making of which he made other fine films, including Murder On The Orient Express (1975)) with Network, a satire about U.S. TV and its almost fatal obsession with ratings.

Given its subject matter, it was entirely appropriate that Network was written by Paddy Chayefsky, arguably the first great TV writer with Marty (1953). Nearly a quarter of a century later, Chayefsky returned to television as a subject, assessing what had changed in the medium in the intervening two decades and was both amazed and appalled by what he discovered.

Like Chayfesky, Lumet had begun his career in television in the 1950s and he assembled a typically brilliant cast to play the broadcasters and the executives who were increasingly the bane of their lives, bringing Chayefsky’s singular vision thrillingly to life.

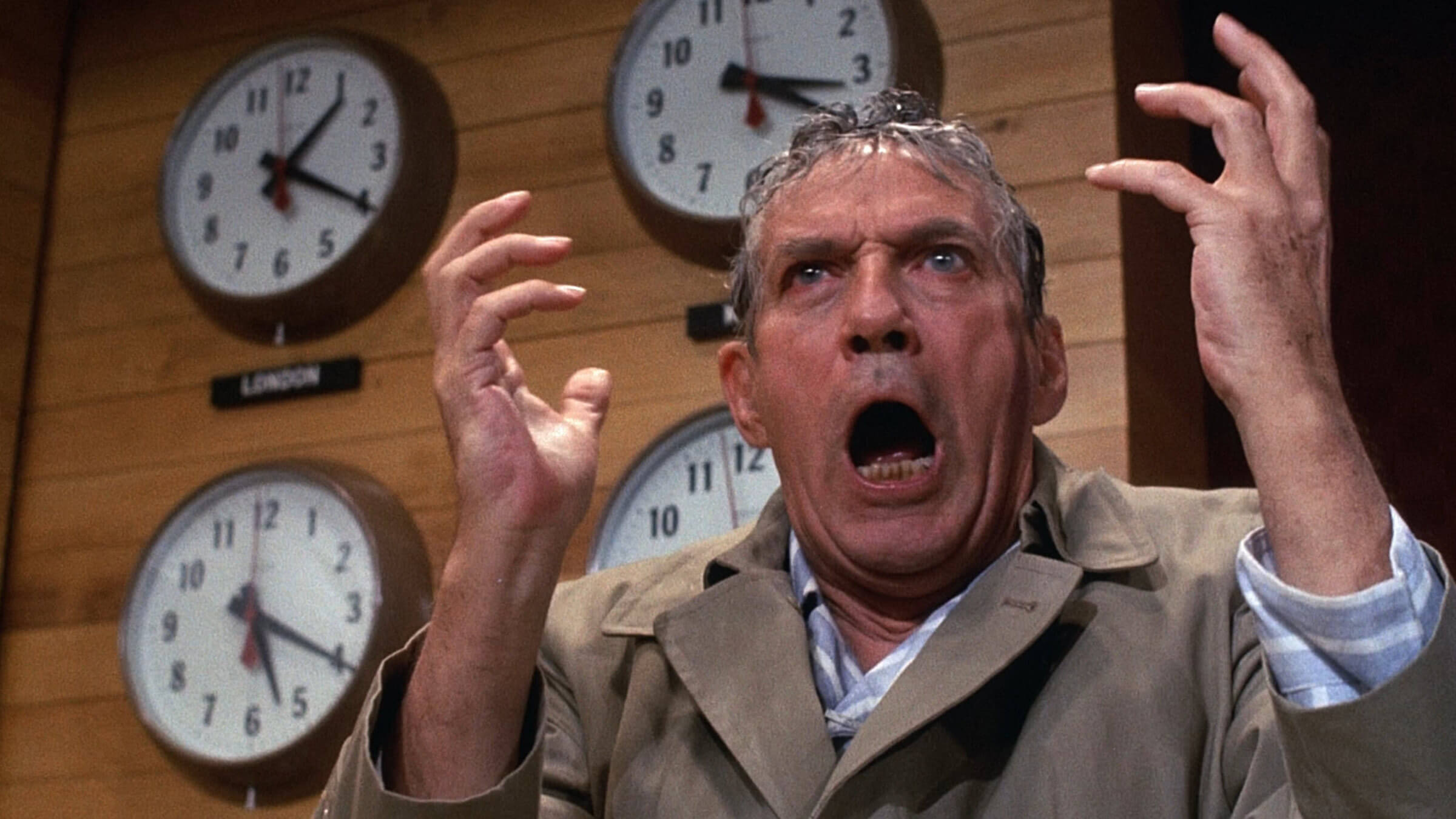

Of all the Sidney Lumet movies, Network is most famous for what is arguably the single most famous speech in film history, Peter Finch’s searing monologue, direct to camera, in which he laments at the end of one newscast, “I’m as mad as hell, and I’m not going to take this anymore!” He invokes his viewers to do and shout the same, and to a large extent, the whole of America followed suit. In the 1970s, the first decade in which American exceptionalism was really called into question by a succession of scandals and controversies, from Vietnam to Watergate, Chayefsky, Lumet and Finch gave voice to a whole generation’s frustrations.

In his seminal book, Adventures In The Screen Trade, which is equal parts autobiography, Hollywood history and screenwriting guide, the great William Goldman wrote about the 1977 Oscars, at which Network received 10 nominations, including Best Picture. He described it as an Oscars that reflected one of the greatest ever years in American cinema, with the other films nominated for Best Picture being All The President’s Men (which Goldman himself had written), Taxi Driver, Bound For Glory and Rocky.

As Goldman wrote, 1976 was a highwater mark for American film-making in general and the New Hollywood of Scorsese, Coppola and Lumet in particular. However, that golden age would soon be ended by another film made in 1977 that did not receive any Oscar nominations but would nonetheless change film-making forever, in a way that arguably no film before or since has done. That film, of course, was Star Wars and its monstrous, almost culture-consuming (or at least cinema-consuming) success eventually signaled the end of the Second Golden Age of Hollywood, as the American film industry pivoted away from the great, serious, truly adult dramas of the first half of the 1970s, such as The Godfather, Chinatown and Network, and towards the sci-fi/superhero/fantasy model that remains the dominant form of film-making today.

Like so many other great American 1970s filmmakers, Lumet suffered from this cultural sea change. He still made films and interesting films at that, including the very different Equus (1977) and The Wiz (1978), but it was not until The Verdict in 1982 that he found another quintessentially serious, hard-hitting drama to compare with his best output of the 70s and 12 Angry Man.

The Verdict (1982)

The Verdict was a classic courtroom drama, based on a source novel by a practicing lawyer that was superbly adapted for the screen by a young David Mamet. Using Mamet’s sparse but brilliant script and casting Paul Newman, in arguably his last truly great screen role, to play an alcoholic lawyer who tries to pull himself together sufficiently to win a medical malpractice suit, The Verdict was a return to form and success for Lumet. It proved that even in the age of Star Wars, serious dramas of the kind Lumet excelled at making could still be made.

Read More: David Mamet’s Three Magic Questions

Despite the critical and commercial success of The Verdict, there is no denying that the second half of Sidney Lumet’s directorial career, from 1982 to 2007, was much less successful than the first half, in which he had established himself as one of the greatest American directors. He continued to direct – throughout his long career of 50 years, he made over 40 films – and still had occasional successes, such as Running On Empty (1988) and Q & A (1990). However, none of those films from the 1980s, 1990s and noughties compare to his masterpieces of the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s.

Nevertheless, Lumet’s last film, Before The Devil Knows You’re Dead, was a fitting swan song. Its title derived from the old Irish saying: “May you be in heaven a full half-hour before the devil knows you’re dead.” That would be the ultimate example of getting away with something: escaping judgment before your sins, or crimes, could be fully assessed. As such, it was perfect for the story of a pair of brothers who decide to rob their parents’ jewelry store for the insurance money, only for the whole escapade to go as disastrously wrong as the events of Dog Day Afternoon.

Unlike most of Lumet’s linear, even straight-ahead dramas, Before The Devil Knows You’re Dead had a complex, non-linear structure. Otherwise, however, it featured many of the classic Lumet traits: a small-scale crime drama, based on a strong script and acted by a superb ensemble led by one particularly stellar actor. In Before The Devil Knows You’re Dead, that star actor was Philip Seymour Hoffman.

Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead (2007)

Seymour Hoffman was probably at his peak and should have followed in the footsteps of Fonda, Pacino, Cazale, Finch and Newman in using a great Sidney Lumet film as the springboard to even greater success. Unfortunately, indeed tragically, it wasn’t to be. Fine film though it is, Before The Devil Knows You’re Dead was not as masterful as 12 Angry Men, Serpico or Network, and within four years Sidney Lumet would be dead, at the grand old age of 86 and within another three years Seymour Hoffman would be dead, too, aged just 46, from a heroin overdose.

Nevertheless, over a full half-century, Sidney Lumet made nearly 45 films of which at least nine (the first five in this collection plus The Pawnbroker, The Hill, Fail Safe and The Offence) are masterpieces. That is a remarkable batting average for any director and undoubtedly puts him in the front row of great American filmmakers.