By Martin Keady · March 27, 2024

It is often said that “doc ‘n’ roll [documentaries about great bands] is the new rock ‘n’ roll,” and that is probably true; it is certainly hard to think of any current musicians who, in 30 years, will have films made about them that are as good as, say, Once Were Brothers: Robbie Robertson and The Band (2019). However, it might be possible to go further and argue that documentaries are the new cinema, telling the kind of powerful human stories that are so often absent now from many mainstream movies because of their tedious fixation on sci-fi, sci-fantasy, and superheroes.

Here, then, is an alternative history of film, which stretches from the birth of cinema to the present day, focusing on the greatest documentaries ever made.

The first film is also the first documentary, which is quite the achievement for a grainy, blurry, indeed distorted piece of film that lasts for just two seconds. That is the Roundhay Garden Scene, which is most likely the oldest surviving motion picture.

In the second half of the 19th century, which saw a genuine technological revolution that puts today’s so-called “big tech” to shame, there were many attempts to make moving pictures (movies). However, the real breakthrough was made by Louis Le Prince, a Frenchman who relocated to the north of England, the home of the Industrial Revolution, to realize his ambition of making the first film. Le Prince finally succeeded with what is known as the Roundhay Garden Scene.

It is brief, simply showing Le Prince’s son, Adolphe, another man, and two women (whose names are unknown) setting out for a walk from a country house before the film distorts and stops. However, just as Neil Armstrong’s one small step on the moon was a giant leap for mankind, this literal fragment of film is the starting point for the billions of hours of film that have followed since.

Roundhay Garden Scene is film before it was formally called film, and, crucially, before it was divided into fiction (the features most often thought of as movies) and fact (documentaries). It is a reminder that, to some degree or other, all films are documentaries, literally documenting or even capturing reality, or some approximation of it.

Read More: What Was the First Movie Ever Made?

For the next thirty years, there was still no real division between film and documentary. That was why Robert J. Flaherty was able to make Nanook of the North, which was ostensibly a “documentary” about the titular Inuit but employed filmmaking techniques that would probably preclude it from being called a documentary today.

Yet Nanook of the North is still an extraordinarily beautiful record of a life and lifestyle that is now largely lost. Almost despite himself, Flaherty did capture some of the truth of Inuit life a hundred years ago. A century later, when the world is facing (or rather ignoring) the destruction of the last surviving Indigenous peoples, it is arguably more relevant than ever.

Read More: The History of the Screenplay

Man with a Movie Camera was not the first “city symphony,” as such films were called (that was probably Walther Ruttman’s Berlin: Symphony of a Metropolis (1927), which gave its title, or part of it, to this new sub-genre of documentary), but it was the best. This is because Vertov made documentaries stylish with seemingly endless manipulation of the images he shot, using techniques such as slow motion, freeze frame, and jump cuts (over thirty years before Jean-Luc Godard made them revolutionary). That approach even extended to filming himself, the titular Man. In one particularly ingenious image, Vertov appears inside a beer glass.

He also provided probably the best definition of documentary cinema when he wrote in his film book, Kino-Eye: The Writings of Dziga Vertov, “Down with bourgeois fairytale plots and scenarios—long live life as it is!” Strip away the Communist party-speak, which he was compelled to espouse, and that dictum still holds true today.

Read More: When Was the Movie Camera Invented?

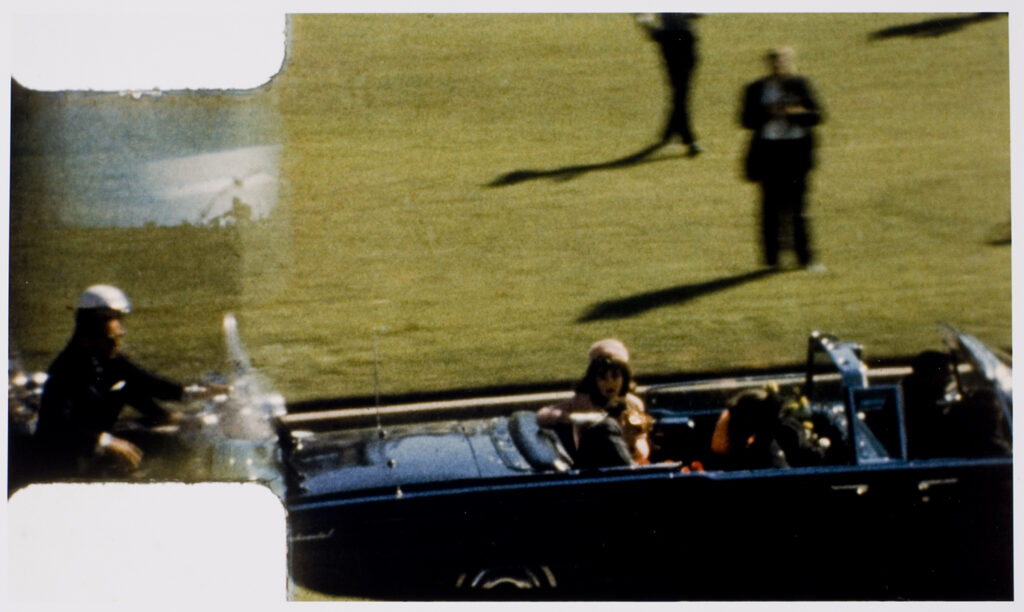

It’s the film that everyone forgets is a film, let alone a documentary, but Abraham Zapruder’s home movie, which inadvertently captured the assassination of John F. Kennedy on November 22nd, 1963, is possibly the single most important piece of film from the 20th century.

Zapruder was far from the only person to capture footage of that fateful day, but his silent 8 mm color film, which lasts for less than 30 seconds, recorded the best view of Kennedy’s motorcade.

‘Zapruder Film’ (1963)

Realizing what he had filmed, Zapruder surrendered his footage to the investigating authorities. Instantaneously, it became probably the single most studied, indeed forensically examined, film ever made. It was key evidence in the Warren Commission, the formal body established to investigate the assassination, but it was quickly released (or leaked) to the media and both the full footage and the slowed-down frames were soon seen all over the world.

Zapruder later claimed that he had a nightmare in which he saw a Times Square billboard proclaiming, “See the President’s head explode!” and he even tried to block that particular frame of the film from being released. His nightmare might not have come true in a literal sense, but metaphorically it has with the worst excesses of 21st-century screen culture, in which serial killers and terrorists invariably attempt to film (or even livestream) themselves while carrying out atrocities.

To describe Shoah as the “ultimate” or, worse still, “best” Holocaust documentary seems absurd, even an invitation to ridicule; indeed, it is a reminder of one of Woody Allen’s best jokes in Annie Hall (1977), namely that in the future there might be an award for “Greatest Fascist Dictator.” Yet, there is no denying the singular power of Claude Lanzmann’s documentary.

Since the end of WWII, there have been several incredible documentaries about the Holocaust, including Alain Resnais’s Nuit et Brouillard (Night and Fog) (1956) and Marcel Ophuls’s Le Chagrin et la Pitié (The Sorrow and The Pity) (1969). Yet Shoah stands alone.

That is because Lanzmann’s film, which is over nine hours and took him more than a decade to make, captured not only the victims of the Holocaust but the instigators of it, including SS Officers. It also includes numerous testimonies from survivors, who calmly recount the horrors they were part of, including burning their fellow prisoners’ bodies after they had been gassed. “Shoah” is Hebrew for catastrophe and Lanzmann shows that the Holocaust was a catastrophe not just for the Jewish people, the Romani people, and all the others that the Nazis were intent on destroying, but for all humanity.

Read More: What Is The Longest Movie Ever Made?

In the 1990s, many documentaries were made to commemorate “The Century of Cinema,” as the 20th century has often been called. However, the best documentary about film history had already been made in 1988. Consequently, whether he knew it or not, Godard was celebrating the actual birthday of cinema and paying homage to the true founder of film, his compatriot Le Prince.

‘Histoire(s) du cinéma’ (1988)

It is fascinating to consider how far film had developed (pun intended) in the century between Le Prince’s Roundhay Garden Scene and Godard’s Histoire(s) du Cinema; indeed, Godard shows how film had exploded, both in popularity and influence, during that time. In the process, he also foresaw the future, with one critic calling Histoire(s) du Cinema a “hyperlink film that takes in ‘everything.'” It certainly takes in the history of cinema to that point, with Godard “quoting” or even “sampling” (in keeping with the emerging musical technology of the 1980s) from films ranging from Jean Vigo’s Zero de Conduite (Zero for Conduct) (1933) to Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Teorema (Theorem) (1968).

When Godard died in 2022, many critics and former fans lamented the fact that, after his imperious 1960s, he had ultimately lost his way as a filmmaker because he became more interested in politics, especially Marxism, than movies. But with Histoire(s) du Cinema, Godard managed to fuse his early iconoclasm with his later theorizing to make arguably his last great film.

Read More: The Best Foreign Films You Have To See

The “sports doc” is now firmly established as a sub-genre, with outstanding examples including Steven Riley’s Fire In Babylon (2010), about the great West Indies cricket team of the 1970s, and Asif Kapadia’s Diego Maradona (2019). Yet the Citizen Kane (1941) of sports documentaries is surely Steve James’s Hoop Dreams (1994).

It is almost paradoxical that Hoop Dreams is celebrating its 30th anniversary because it is all about childhood dreams, specifically the dream of so many young African Americans to make it as a professional basketball player. James filmed two African-American teenagers, William Gates and Arthur Agee, as a largely white high school recruited them for its basketball program. What follows is the story of the two boys as they try to make it to the NBA, in the process confronting obstacles ranging from racism to sibling envy.

It is appropriate that two of the finest documentaries ever were made by two of the greatest film directors, Godard and Agnès Varda. That is because many film directors, from Martin Scorsese to Werner Herzog, have made documentaries as well as features. Yet Godard and Varda are the two greatest filmmakers to have made great documentaries.

As aforementioned, Godard’s doc was a typically ambitious film about 20th-century cinema. By contrast, Varda, who began making films in the 1950s but was then largely overshadowed by nouvelle vague (or French New Wave) directors like Godard, made a deeply personal documentary about les glaneurs, the human scavengers who survive on the fringes of society by gathering together, or gleaning, the objects and even the food that others throw out.

In English, the word “glean” has two meanings: first, to scavenge, as Varda herself eventually does in the film, by collecting leftover crops from harvests or even supermarket leftovers, and, secondly, to obtain information from a variety of sources. Ostensibly, Varda’s film is about the outcasts of society, with whom she identifies, but it is also about how we glean information from different sources. Thus, it is fitting that a film about collecting leftovers should become so far-ranging, at one point even examining the origin of cinema.

Read More: 10 of the Best Scripts Written by Women

Like The Gleaners and I, David Simon’s The Wire (2002-2008) foresaw the rise of the “working poor,” especially in its final season. Well, if there is a documentary equivalent of The Wire, the greatest TV series ever made, it is Eugene Jarecki’s 2012 documentary, The House I Live In, about the war on drugs and the deadly toll that “war” exacts on young African American men.

Simon is one of the contributors to The House I Live In, which only increases the tendency to make comparisons between it and The Wire. Yet their real point of similarity is that both works (one fictional, one documentary) adopt the same approach: the detailed, indeed forensic, examination of individual stories, which inevitably leads to the equally forensic examination of wider societal issues. Jarecki tells the story of his childhood nanny, an African American woman whose own son, also Jarecki’s childhood friend, ends up being incarcerated.

The House I Live In is one of the greatest 21st-century documentaries, which is why it deserves to be compared to The Wire, or, better still, regarded as its non-fiction companion piece. Both together reveal the ongoing tragedy of America’s treatment of its former slaves and their descendants.

The best music documentary ever is not Dont Look Back (1967), D.A. Pennebaker’s Bob Dylan doc, which virtually invented music documentaries. Instead, it is a film of far more recent vintage, Julien Temple’s A Crock of Gold: A Few Rounds With Shane MacGowan.

Temple is a great punk filmmaker, but this film is his crowning glory because it shows how the original rush of punk in the 1970s, especially in London, inspired countless others to change their own lives, including MacGowan, who was probably the most famous punk fan of all.

A Crock of Gold: A Few Rounds With Shane MacGowan is perfectly titled. It is golden, as it recounts the truly unbelievable (but true) story of the greatest punk poet. Temple allows MacGowan to tell his own story, spanning from his childhood to his time with The Pogues and the subsequent slow, painful decline. He battled alcoholism from a young age, starting at six, engaged in drug dealing by 12, and underwent electroshock therapy at 14. However, inspired by Johnny Rotten, a fellow ‘Plastic Paddy’ (referring to English-born individuals of Irish descent), he both saved and revolutionized traditional Irish music, penning some of its greatest songs, including “Fairytale of New York,” “A Pair of Brown Eyes,” and “Haunted.”

Read More: Screenwriting 101: How to Incorporate Music in your Screenplay

I am a “Plastic Paddy” myself and I acknowledge that this film may not mean as much to others as it does to me. MacGowan’s transformation into arguably the single biggest reason why being Irish shifted from being loathed during the IRA bombing campaigns of the 1970s and 1980s to being celebrated is revelatory. That’s why, for me, it stands not only as the greatest music documentary ever made but also as one of the greatest documentaries of any kind.