By Alec Siegel · September 2, 2014

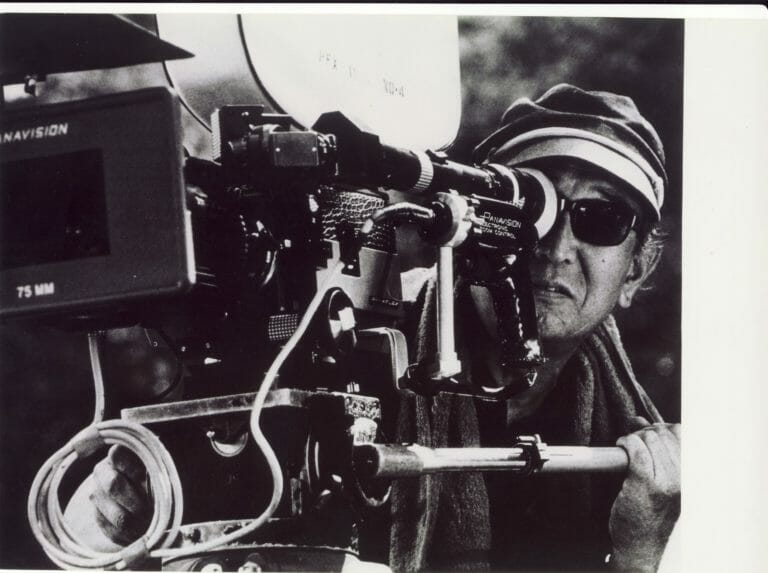

At the end of World War I, the American film industry saw a boom in scale, quality and influence. It was an insulated industry, one with little exposure to the cinema of outside cultures. World War II was a different story. The advent of globalization resulted in a more fluid exchange of ideas and culture. Before WWII, Japanese cinema was among the best in the world, but it was resigned mostly to Asia. America didn’t know of Mizoguchi or Ozu. But after the war, a Japanese auteur by the name of Akira Kurosawa changed that. He had been making great films for years, but his post-war films, some of which were made during the American occupation, reached a new audience: The West. And with that, he eventually became regarded as one of the world’s greatest filmmakers, perhaps the greatest to ever live. The first phase of his career, from the early 1940’s to the early 1950’s, is characterized by films with ultra realistic, simple plotlines inhabited by multi-dimensional, highly relatable characters in post-war Japan. Kurosawa’s first decade was an eventual master of the art form developing his voice, and consistently innovating in terms of technique and storytelling.

For this series, I will be discussing not all of Kurosawa’s movies, but those that mark certain innovations and shifts in periods in his career. These films are not necessarily his best (though many of them are), but are the most important in the scope of his career.

Kurosawa’s film career technically began in 1936, when he worked as an assistant director under Kajiro Yamamoto for the new Japanese film studio P.C.L. He was 25 years old at the time, and for five years Kurosawa worked as A.D. on 24 films, most of which were directed by Yamamoto. It wasn’t until 1943 that his career began in earnest, when he would release his first entirely self-directed feature Sanshiro Sugata. In the years that followed, he would release five feature films, honing his skills behind the camera, in the editing room and at the writer’s desk. His 1948 yakuza drama Drunken Angel is his first fully formed film. Kurosawa himself said it was the first time he could freely express himself. It was also the first of his 16 collaborations with the legendary Japanese actor Toshiro Mifune.

The film’s titular character is Dr. Sanada (played by another Kurosawa regular Takashi Shimura), a village doctor with an unusual capacity for empathy. He will stop at nothing to cure each and every patient. He is emblematic of a typical Kurosawa character: a drunken angel, a kind man with reckless, self-destructing tendencies. Sanada is a man who helps everyone but himself. Mifune plays Matsunaga, a yakuza member recently diagnosed with tuberculosis by Dr. Sanada. Matsunaga is likewise full of contradictions and complexities. He is a yakuza, a gang member. Yet he plucks a fresh flower every morning from the florist. He is on the precipice of true darkness, but he can’t quite take the full dive. The film follows the two as they butt heads, yet also help each other. It’s the type of character driven film that typified Kurosawa’s early films. A man with tireless energy and much to say, Kurosawa released two films a year later, in 1949, the second of which, Stray Dog is among his best of the period.

Stray Dog is an early example of the buddy cop, hard-boiled detective film, with tea instead of coffee, and the suffocating Tokyo heat instead of a harsh New York winter. In terms of the film’s technical qualities, it’s up there with Kurosawa’s very best. The “window swiping” editing technique that he often used in lieu of a jump cut has a kind of turning the page kind of effect. When moving to a new scene, a line swipes from one side of the screen to the other, instead of simply jumping there as a jump cut does. This technique has a very kinetic feel, a fluidity that resembles turning the page in a novel rather than abruptly cutting to the next scene.

Mifune is excellent as Detective Murakami, an obsessive WWII veteran fresh off the battlefield, who’s thrust into the criminal underbelly of Tokyo. His gun is stolen while he’s riding on the trolley, setting the very linear, interrogate one suspect and move on to the next type of plot in motion. Murakami is obsessed with finding his gun, and blames his own carelessness for the crime its new owner commits.

Extreme weather often plays a role in Kurosawa’s films. He finds the elements to be an effective means of expressing either a character’s feelings or his own ideas. Kurosawa likes extremes. They’re the most alive. Stray Dog takes place during a summer heat wave in Tokyo. It seems like every scene has somebody either wiping his or her brow or neck with a handkerchief or sitting in front of a rotating fan. Murakami and Detective Sato (Takashi Shimura), a mentor figure to Murakami, stumble around the sweltering metropolis like two panting dogs, on a never-ending scent trail of their suspect. The master-student dichotomy is one Kurosawa often explores in his films, and Sato dispenses valuable advice to Murakami throughout. Their relationship is typical of the crime genre. A seasoned cop is paired with a green newbie, whose naivety and enviable ignorance inevitably reminds him of himself before the cruel world jaded him.

Stray Dog is a wonderful example of Kurosawa’s finesse with a camera. He has an innate ability to use nuanced camera movements and shots to express his ideas. He was one of film’s earliest technical masters, and many modern day filmmakers borrow from his toolbox. Steven Spielberg has referred to Kurosawa as “sensei”. He doesn’t lean on unnecessary dialogue. His scripts are as lean as they come. There’s an 8-minute sequence in the film where Murakami dresses as a war veteran, roaming the streets on an obsessive quest to retrieve his gun. There is no dialogue. No action. We simply brave the Tokyo heat wave with him, feeling as suffocated and desperate as he is. Kurosawa is a product of silent film, and his economic usage of dialogue is refreshing to watch in the current movie climate that’s filled with lazy dialogue and over the top sound effects. Kurosawa’s films to this point were still largely only known to those in Japan. International recognition had yet to come. In 1950, his film Rashomon introduced him to the wider world. The film won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival, officially announcing Kurosawa as a global force in film.

Many sitcoms and romantic comedies or detective shows and films have directly lifted a technique invented by Rashomon. Even an episode of Rugrats has used a technique lifted from this iconic film. Here’s what Rashomon invented: a group of friends sit down in a living room, and explain to an uninformed guest their respective perspective on a shared experience, which is shown in flashback form. Seinfeld might not exist without Rashomon. Nor would Criminal Minds. Ok, maybe they would, but there is no denying the influence the film has had on the film and television mediums.

Rashomon tells four different versions of the same story, each by a different player in the story. The central conflict is the killing of a samurai who was travelling through a forest while escorting his wife. Who killed him? And how did he die? We see the story through the eyes of a bandit (Toshiro Mifune), the wife, the dead samurai (via a medium), and a woodcutter. Mifiune as the bandit, who has admitted to raping the samurai’s wife and claims to have honorably killed the samurai in a duel, is the closest thing to a main character. The bandit is far different from the clean shaved urbanite he was previously cast as in Kurosawa’s films. The bandit is a bearded vagabond with a vicious cackle and a wild streak. But he’s also a man with a deep capacity for empathy. Like Kurosawa’s finest characters, he’s difficult to pin down.

Kurosawa’s films generally require great patience from the audience. He likes to stretch scenes until they threaten to split apart. He holds a shot until the film reel burns. Rashomon tells the same story four times, albeit with unique details each time. It’s the character’s motivations, actions and reactions that shift around with each new point of view. Kurosawa questions the motivations of man, his ability to tell the truth to not only others, but himself. Three men take refuge at the Kyoto city gate that shares the film’s title. They banter back and forth about the goodness and the evil of man. About the truth that man may or may not be capable of. They act as the skeptics of the shaky truths presented by each character. Rashomon was a critical and commercial success at the time of its release, but even more so in hindsight. Many publications consider it as one the greatest films ever made. Two years after his first true classic, Kurosawa returned with Ikiru, one of his first films to borrow from Western literature, and the last before his defining samurai period films.

Ikiru, which translates to “to live” in English, tells the bleak story of a man who takes control of his existence only once he learns he’s dying. The film is a striking comment on life’s true meaning, how individuals find meaning in their lives, and how sometimes people are dead long before they actually die. A request put in by a group of frustrated villagers to convert a waste pool into a playground to city hall sets into motion the bureaucratic satirizing that the film deals with. Watanabe-san, the public affairs section chief of a city hall in Tokyo, is a “mummy,” as one observant character notes.

He breathes, eats, and sleeps, but does little else in the way of living life. His son barely acknowledges him, his wife died years ago, and he’s been slowly decaying at his office job for 30 years. He lives, but he isn’t alive. Until he learns he has stomach cancer, and no more than six months to live. At first, getting the most out of life means getting awfully drunk on sake and beer, dancing into the night and going to arcades. Living to Watanabe (Takashi Shimura) means finding a pretty young girl with a zest for life to fill the hole he’s had in his heart since the passing of his wife, and since his son began to neglect him.

And then he dies. Which actually happens about mid-way through the film. Kurosawa, never one to feel restricted by the confines of storytelling conventions, has us follow a man search for meaning in his life, and then has him die with more than an hour left in the film. We learn about the remaining few months of his life through the revealing eulogies courtesy of his co-workers. We learn that he pursued the park request, made it his life’s work in fact. And though he died before he could see it through, he succeeded, and left a cloudy legacy that would at least question the status quo.

Kurosawa’s films don’t feel like fictional stories. They aren’t neatly wrapped stories with implausible yet satisfying endings, happy endings, as many Western films have. No, his films echo reality. They unfold as they most likely would in real life. Watanabe dies midway through the film. A new cancer treatment doesn’t cure him in the nick of time. His son doesn’t deliver a tearful apology for his years of neglect. This is the Kurosawa way. His stories don’t always end comfortably, but it’s that discomfort that leads to great reflection. After Ikiru, Kurosawa would begin a long, career defining stretch of samurai epics. His mastery of the technical aspects of filmmaking would only expand, as would his audience and worldwide acclaim. Stay tuned.