By Martin Keady · January 25, 2023

The surest proof of a screenplay’s greatness is that the story of its writing becomes the subject of a film or TV series. Citizen Kane begat Mank, David Fincher’s biopic about Kane’s writer, Herman J. Mankiewicz, and the backstory of The Godfather became The Offer, the Paramount+ TV series. And the same may yet happen with Chinatown after it was widely reported that Ben Affleck would direct a dramatized version of Sam Wasson’s book about its making, The Big Goodbye: Chinatown and the Last Years of Hollywood.

Although Affleck’s film may eventually prove to be yet another victim of the hit that cinema has taken from the pandemic, the fact that a “Making of Chinatown” film was even mooted is a testament to the film’s enduring, indeed almost mythological, status. But why? Chinatown, in general, and its screenplay still come with much fascination, to the extent that not only are books and possibly films about it produced but it is widely regarded as the greatest screenplay ever written.

Well, here are some of the reasons why.

Download the script!

A major part of the fascination with scripts and films such as Citizen Kane, The Godfather, and Chinatown is undoubtedly a nostalgia for cinema itself and the power – both economic and cultural – that it once had. The title (and indeed subtitle) of Wasson’s book, The Big Goodbye: Chinatown and the Last Years of Hollywood, epitomizes that nostalgia for a time when cinema was literally the greatest show on earth and films such as Chinatown could be not only enormous box-office successes but artistic masterpieces.

Wasson effectively identifies Chinatown as the last truly great film of Hollywood’s second golden age, which lasted roughly from the end of the 1960s to the end of the 1970s. Although other great Hollywood films were made in the second half of the 1970s, such as The Deerhunter (1978), Apocalypse Now (1979), and Being There (1980), Wasson is probably right that the mid-1970s was the peak of this second golden age of American film-making (the first golden age having come roughly between 1940 and 1960 and thus lasting much longer than the second). It was certainly the peak for screenwriting, with 1974 occupying the same place in the history of Hollywood screenwriting that 1939 occupies in the history of Hollywood film-making in general, i.e., its peak.

Read More: Was 1974 the Greatest Year for Screenwriting Ever?

So, as the title (and subtitle) of Wasson’s book suggests, part of the adoration of Chinatown is the fascination for that extraordinary period in American cinema when huge budgets were used not to make superhero films (as is invariably the case now) but serious, complex, grown-up movies about America and its twin obsessions with money and power. Nearly half a century on, it is arguable that only TV’s Holy Trinity of The Wire, The Sopranos, and Mad Men have come close to replicating the sheer power of screen storytelling that Chinatown and The Godfather movies achieve.

However, nostalgia for cinema and its glorious past is not the only reason why Chinatown and its screenplay by Robert Towne remain so revered. Such nostalgia is an external or extrinsic factor; it is the intrinsic qualities of the screenplay itself that are the main reason it is so celebrated.

The three main elements of any screenplay are plot, dialogue, and theme, which is essentially what the screenplay is trying to say – in other words, what it means. In each of these three elements, Chinatown is outstanding.

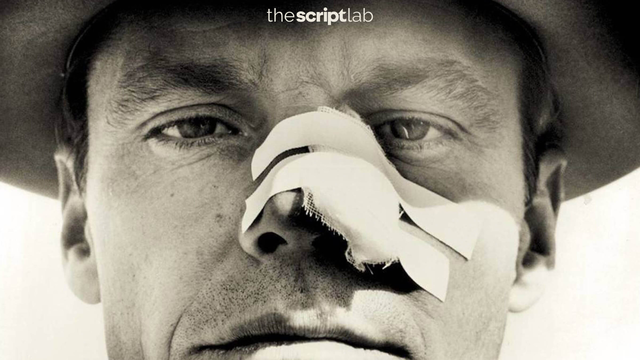

Chinatown (1974)

Beware: There is a spoiler buried below.

The plot of Chinatown is complex; indeed, it is so complex that it is doubtful that such a complex film would be made today. Rereading the screenplay in preparation for writing this piece, I was struck again, as I was the first time I saw the film, by just how difficult it is to follow what is happening, let alone understand everything that is going on. And yet that is entirely appropriate because Chinatown is a film about complexity and how hard it is to understand the world. As Noah Cross, the piece’s villain, famously says: “You may think you know what you’re dealing with, but believe me, you don’t.” That line is almost the maxim of Chinatown.

However, it is also almost the maxim of the modern world. The extraordinary complexity of globalized human relations and economic systems can make it difficult, if not impossible, to identify the precise cause of anything.

The nominal plot of Chinatown is that Jake Gittes (a private eye played in the film by Jack Nicholson) is hired by a woman, Mrs. Evelyn Mulwray, to find proof that her husband is having an affair. So far, so Philip Marlowe, but almost immediately, this storyline is revealed as a red herring because the real Mrs. Mulwray (played by Faye Dunaway) appears in Gittes’s office to chastise him for slandering her family.

This initial setup is typical of how the entire screenplay works. After Gittes realizes he has been duped, he sets out to find the truth, ostensibly to salvage his professional reputation but in reality to satisfy his curiosity about what has happened. Gittes (whose name may be a play on “git,” the old English word for an unpleasant or stupid person) becomes the proxy for the reader of the screenplay or the viewer of the film as he uncovers an intricate plot (which Towne always insisted was based on the actual history of LA) to use the city’s limited water supply to gain power. However, it eventually becomes apparent that Noah Cross’s ambitions are political and personal and that he treats his family even more appallingly than he does the civic authorities.

Chinatown (1974)

As suspected, there is another spoiler below.

The second major element of any screenplay is the dialogue: what the characters say and how it can often be completely different from what they mean or do. Towne’s dialogue in Chinatown is masterful, recreating the wisecracking of the original 1940s noirs but updating and darkening it to cover subjects that would never have been included in those original noirs as they were deemed too controversial or just taboo.

Chief among those subjects is incest, which Gittes eventually realizes is the original sin Cross committed before he began raping the land surrounding LA for its water. The famous scene in which this is revealed is typical of the hard-hitting nature of Chinatown’s dialogue, which makes even the supposedly “hard-boiled” dialogue of earlier noirs seem soft-hearted by comparison:

GITTES:

I said the truth!

EVELYN:

She’s my sister.

Gittes slaps her again.

EVELYN (continuing):

She’s my daughter.

Gittes slaps her again.

EVELYN (continuing):

My sister.

He hits her again.

EVELYN (continuing):

My daughter, my sister.

He belts her finally, knocking her into a cheap Chinese vase which shatters, and she collapses on the sofa, sobbing.

GITTES:

I said I want the truth.

EVELYN (almost screaming it):

She’s my sister and my daughter!

This exchange between Gittes and Evelyn is the most celebrated in the entire script. However, the same power, precision, and, for want of a better word, discomfort is evident in virtually every line. To give just one example, earlier Evelyn phones Gittes in the office he shares with two other private detectives and asks, “Are you alone?”, to which Gittes immediately replies, “Isn’t everyone?”

This casual, almost throwaway remark is similar to another apparently off-hand remark in a classic film that actually sums up the dark nature of the world that is being depicted. It comes in Get Carter (1971), the greatest British gangster film ever made, in which Michael Caine’s Carter first confronts Eric Paice, an old acquaintance he suspects has involvement in his brother’s death. Eric is so shocked to see Carter/Caine again after many years that he exclaims, “Good God!”, to which Carter/Caine immediately replies, “Is he?”

The lesson for any screenwriter is to ensure that every line of dialogue counts. The infamous exchange between Gittes and Evelyn in which he learns the truth about her is celebrated as great screenwriting, but so is the seemingly casual, apparently unimportant exchange on the phone from earlier in the story.

Chinatown (1974)

The theme is the most challenging part of any screenplay to identify, but it is arguably the most important. Put simply; it is what the story is actually about – what it means or tries to say. And the theme in Chinatown is just as elusive as its plot and dialogue.

When Noah Cross tells Gittes that he doesn’t know what he’s dealing with, Gittes’s response is instructive. Before he even says anything, the screen direction says:

“This stops Gittes. He seems faintly amused by it.”

This unusual reaction prompts the following exchange:

CROSS:

What’s so funny?

GITTES:

It’s what the D.A. used to tell me about Chinatown.

CROSS:

Was he right?

GITTES shrugs.

We never find out what happened in Chinatown that led to Gittes leaving the police and becoming a private detective; it is only hinted at by Gittes later when he suggests that he had tried to do right by someone but only ended up doing them wrong. Robert Towne said that this was the real theme of Chinatown: the impossibility of doing good in a profoundly imperfect world. That is a world away from the optimism and hopefulness of most movies’ themes, especially those made in Hollywood.

Chinatown (1974)

As Wasson’s book and its rumored screen adaptation proves, Chinatown has had a remarkable afterlife. More than 15 years later, a sequel called The Two Jakes (1990) reunited most of the key players from the original. However, The Two Jakes was a creative and commercial flop, in the same way that The Godfather Part III was a year later. But just as with The Godfather (Parts I & II), the failure of the sequel has done little to harm Chinatown’s reputation.

In his book, Wasson argues that Roman Polanski, who directed Chinatown, rewrote Towne’s original screenplay.. In particular, Polanski insisted on a far darker ending than Towne had initially envisaged. Towne had wanted something vaguely approximating a happy ending, but that wouldn’t wash with Polanski, who had suffered his own “LA Tragedy” in 1968 when his pregnant wife, Sharon Tate, was murdered by members of the Manson family. Having experienced such a terrible crime himself, Polanski knew that there could be no escape for Evelyn, another innocent in a city full of sin. He rewrote the ending to reflect that.

The authorship of the greatest screenplays, from Citizen Kane to Chinatown, is almost always bitterly contested, proving that the old line about the music business – “Where there’s a hit, there’s a writ!” – is equally true of the movie business. But ultimately, who wrote what is less important than what was written. Chinatown may not be the best screenplay ever written, but, to adapt a famous line of the great Brian Clough when he was asked where he ranked himself among football managers, it’s “in the top one.”