By Ben Larned · June 10, 2018

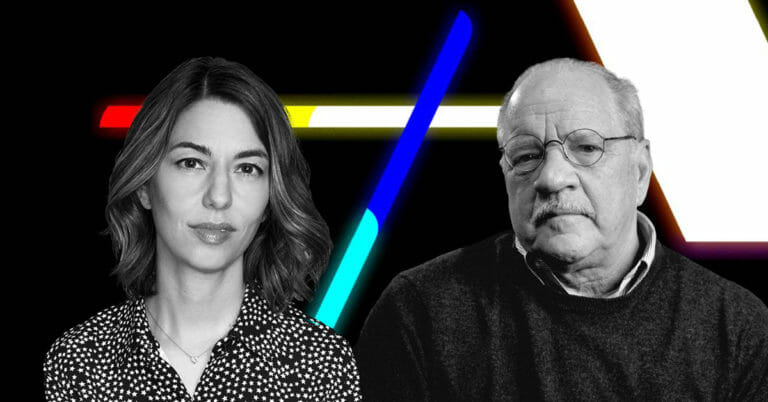

In a culture driven by image, influence and followers, it’s easy to forget that art only carries as far as its voice – and only lasts as long as its voice is true. For their fourth podcast episode, groundbreaking indie studio A24 unites two artists – Sofia Coppola (The Virgin Suicides) and Paul Schrader (Taxi Driver) – whose work continues to define the eras in which they were made. On the heels of Schrader’s latest film, First Reformed, he joins Coppola in a conversation about finding material and voice while navigating our uncertain times.

To start, the filmmakers asked an effortlessly disturbing question: how does one get a movie seen today? Recalling the release of his iconic film Taxi Driver, Schrader says that much of a film’s life is determined by luck. One must gain the approval of the gatekeepers – festival programmers, press, distributors – but once a film reaches its audience, promotion becomes utmost in expanding it. Coppola notes, it’s a full-time job to promote a film, especially during awards season (Labor Day to April). Even iconic filmmakers can’t avoid waiting, either. It took the distributors several months to gauge a proper release plan for First Reformed, for instance – but this is an essential part of the process.

Working with studios and executives remains a frustrating necessity as well. Schrader recounts a period from several years prior, when a bad studio experience sent him into despair – “This is how my career’s gonna end, with a fiasco.” Coppola and Schrader both speak to this fear: every film could be your last, especially when your focus isn’t commercial success, but art. So how do you make a film with executives and business people who, as Schrader points out, don’t even engage with or enjoy the medium? This is a tension that neither Coppola or Schrader have a solution for; it’s simply an obstacle to be aware of.

Of course, one can’t promote a film without having first made one. Finding material can be one of the most challenging aspects of a filmmaker’s career. “After every film,” Coppola says, “you go through that period of searching.” As a critic, Schrader found it difficult to lean into “trashy,” commercial film without elitism getting in his way. To write Taxi Driver, he had to humble himself and engage in a seedier side of life. Similarly, it took him an entire lifetime to gain the courage to tackle spirituality in First Reformed. Metaphorical distance between the artist and the subject is essential for Schrader, however; he believes that his weakest films are the ones that he wrote about his mother and father, respectively. It’s about finding a common thematic ground, but a unique, specific context in which to explore the ideas.

Schrader’s search for material has also illuminated the cyclical nature of his characters – the lonely anarchist of Taxi Driver to the despair-swallowed priest of First Reformed – as a way for his art to explore the stages of life. Coppola agrees that elements of her work return organically; she’ll examine a story from afar and realize that she has stumbled upon the same theme. That doesn’t mean an artist can tell the same story over and over again. Schrader speaks to the fun of his ill-received The Canyons: he did it as a challenge, to see if he could pull it off. Coppola notes that her father made The Conversation as a riff on Blow-Up, but the process of recreation forced him to come up with something new.

Read More: The Human Focus in Sofia Coppola Movies

That freshness can sometimes emerge through acknowledgment of the filmmaker’s era. When discussing the origins of his latest project, Schrader and Coppola both agree that a self-aware writer can’t avoid addressing the preoccupations of the time. With First Reformed, Schrader tackles the age-old conundrum of our purpose in the world, something many of us cringe to contemplate. How does one explore this unanswerable issue through art? You can’t push your audience into a grand mystery, Schrader believes; you can only guide them and encourage them to jump forward.

With that in mind, Coppola and Schrader ask, how do you stylistically “corner” a viewer so that they jump into the mystery? Schrader uses narration to “intravenously feed” the viewer information (though this isn’t the strongest path for novice writers). He also prevents the film from taking on other perspectives, so that the viewer can’t help but see through his protagonists’ eyes. It’s a trick that one can spot in much of Schrader’s work – his characters are dark and often morally questionable, but it’s hard to abandon them once we’ve witnessed their innermost anxieties. Considering the tumultuous state of our world, this kind of empathy seems invaluable.

While their conversation points out a disappointing truth – even filmmaking legends struggle to find success for their work – Coppola and Schrader remind us of the essentials. By seeking truth and reflection in your work, it can find a genuine, universal voice. Will it carry above the din of other creators? That’s for time (and the gatekeepers) to decide. But, as long as human beings seek answers for these overwhelming questions of existence and faith, we can continue to provide art that illuminates the conversation.

Listen to the fourth A24 podcast below.

Do these discussions help you in your own process? Keep up with A24’s podcast, and The Script Lab, for more advice!

BEN LARNED is an independent genre writer and filmmaker based in Los Angeles. He has written for outlets such as Blumhouse, Bloody Disgusting, WeScreenplay and ScreenCraft. His column Forbidden Tomes is published twice a month on Daily Dead. His short stories have been published in The Book of Blasphemous Words, Danse Macabre, and WitchWorks.

BEN LARNED is an independent genre writer and filmmaker based in Los Angeles. He has written for outlets such as Blumhouse, Bloody Disgusting, WeScreenplay and ScreenCraft. His column Forbidden Tomes is published twice a month on Daily Dead. His short stories have been published in The Book of Blasphemous Words, Danse Macabre, and WitchWorks.

Photo credit: A24.

For all the latest from The Script Lab, be sure to follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.