By Jim Rohner · November 25, 2013

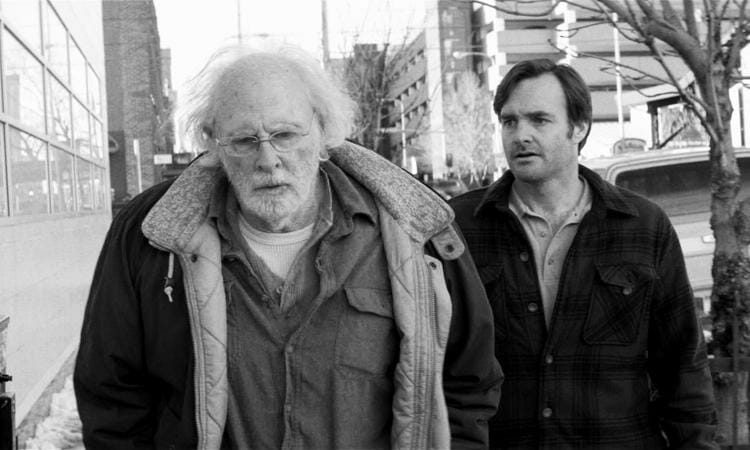

The first time we see Woody Grant (Bruce Dern) is when he's hobbling his way down a highway in Billings, Montana in an effort to get to Lincoln, Nebraska. It's unclear whether or not it's the first time the elderly alcoholic has tried to make the almost 900-mile trek on foot, but it certainly won't be the last.

Unlike many mistakes Woody has made in the past, his attempted elopement has nothing to do with alcohol, as his milquetoast son, David (Will Forte), finds out upon picking him up at the sheriff's station. Woody hands his estranged youngest a wrinkled piece of paper, the contents of which have already been committed to a quickly escaping memory. It's a spam letter, the kind that we all learned to disregard and discard long ago, the kind that promises a $1,000,000 award if redeemed in person (and if a certain number of magazine subscriptions are purchased, and if his number is that one that is drawn, and if, and if…).

David knows that the letter is a scam. David's brother, Ross (Bob Odenkirk), knows that the letter is a scam. David's overbearing mother, Kate (June Squibb), knows that the letter is a scam. Everyone aside from Woody knows that the letter is a scam, but the lack of support doesn't dissuade the old man from repeated attempts to escape. "They can't print it if it wasn't true" he says innocently and pathetically.

Suddenly, David finds himself caught between a rock and a hard place. David knows that there's no money waiting for his father in Lincoln, but he also knows that Woody won't quit, even if it kills him. "The guy just needs something to live for," he justifies to the mother who seems only too eager to see her husband disappointed. The drive to Lincoln is like a march to death – the destination is imminent, the outcome assured, but if his father is to get there, perhaps it should be with David's help.

Even before the father and son duo set out on their road trip, it's obvious that the letter will primarily act as a symbol moving forward; Woody's own personal Rosebud. Yes, the man legitimately believes that he'll soon have enough money to buy a new truck and an air compressor to replace the one he lent to Ed Pegram (Stacy Keach) in 1974, but David's journey to Lincoln by way of Woody's old neighborhood of Hawthorne, Nebraska is also a journey of exploration and understanding of the whats, who's and whys of a father who drank ("there was nothing else to do"), who bore and raised children without inherent affinity or desire of doing so ("I liked screwin' and your mother was Catholic") and who, ultimately, lived a life largely dictated by what others wanted from and for him rather than by what he wanted for himself ("your father never could turn down a favor").

This journey into the past of an otherwise frustrating and inaccessible man is handed deftly and brilliantly by director Alexander Payne, unfolding the layers of a nuanced man piece by piece without the need for sweeping speeches that cheaply lay all the cards on the table. Most of the exposition gleaned from Woody's life and what others expect from him are uncovered by letting other people talk, such as the selfish and oafish aunts and uncles who all feel they're obligated to a piece of Woody's winnings for past assistances or the kind local newspaper editor, Peg Nagy (Angela McEwan), who reflects warmly on the Woody she used to know – the one who came back from Korea a different man.

It would be easy to label the largely silent performance of Bruce Dern as a passive one, but Dern's somberness quietly and effectively invokes the attitude of a man who long ago accepted, rightly or wrongly, that he would never come to achieve what he really wanted (had he actually ever figured out that was). As he stares off into the long-dead corn fields of his now derelict childhood home, we gaze upon the eyes of a man who doesn't care to revisit his past, but who also realizes that with his advanced years and degrading health, there's very little future in which to invest any hope.

The decision to shoot Nebraska in black and white may seem hokey or gimmicky at first, especially since the film's locations don't lend themselves to any stylistic flair (The Descendants) nor its themes to any dichotomies (Sideways). But the further into Nebraska the characters get – both geographically and narratively – the more apparent it becomes that black and white photography can lend a tenderness and nostalgia to the otherwise banal. The fact that a city like Lincoln, Nebraska with a population well under 300,000 acts as the film's version of a metropolis speaks volumes about the plain, back country nature of Hawthorne, but the black and white photography of Phedon Papamichael invokes an emotional significance reminiscent of The Last Picture Show's Anarene, Texas without the implications of stagnation. It's easy to imagine that Woody's return to Nebraska is equivalent to the rediscovery of a black and white filmstrip; a time capsule unchanged since burying.

Nebraska doesn't end with a promise that either Woody or David will be more open and affectionate with each other once they return to Billings, but there is the assurance that more understanding exists than it did upon the journey's beginning. Seeing as Woody is over 70 years old, it would be disingenuous to assume that a simple road trip was all it takes to put aside decades of neglectful parenting. Still, Nebraska acknowledges the existence of nuance in those that shape us, recognizing that they had to be shaped first. Nothing David does or says can alter anything Woody has done or experienced in his prior 70+ years, but he does have some control over what happens in those that remain.