By Anthony Faust · January 26, 2017

When I decided to make my latest film, The Seen (2016), I took a series of unusual approaches. The first was my strategy of choosing a location and writing a story around it as opposed to vice versa. I had known of an old house, dilapidated and in disrepair for many years, but it had never occurred to me that it could be used as a film location.

The genesis of any completed film is a single idea. Here, the idea was not an abstract one, but one physical, with cinder blocks, broken windows, and termite-infested wood. It was not difficult to conceive of a possible dramatic event associated with the place. It was oozing with a vibe that something terrible had happened there. But the question was, how do I film it? And what exactly would I be filming?

I conjured up a scene with a raging house fire, a merciless blaze ripping through the rooms with its unrelenting fury. As the director and the screenwriter of the film, I understood the next step. It all starts with the written word. But as I began to put this idea to paper, the question “how do I film this?” became superseded by one more important, “should I film this?”.

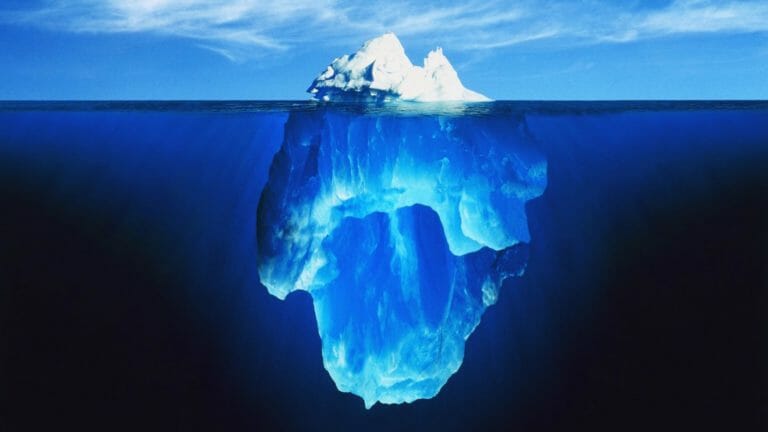

Filming a house fire was impossible because of budgetary reasons so this presented me with the opportunity to experiment with exposition, an approach to storytelling I will call “the iceberg approach”. It’s been said that 90% of an iceberg is under water, hiding under the surface, and the remaining 10% above water. I began to see that the house represented the aftermath of drama that had already happened. The fire was the 90%, the stuff we hadn’t seen. The house was all that was left, the 10% we could see. If I were to show the fire, I would have to use one of the most overused techniques in cinema, the flashback.

Many times, flashbacks have the impact of slamming the brakes on the forward progress of a film, the cinematic equivalent of a storyteller saying, “let me stop you right here and show you something I think you should know before we continue.” So this presented me with a dilemma. If the tragedy of a house fire sits in the past, waiting for its truth to be told with the simple stroke of a pen writing FLASHBACK TO, how do I make this story dramatic if my shoestring budget prevents that tragedy from ever being filmed?

First, the story needed a human face, someone viewers could follow as they immersed themselves with the world this house occupied. That gave me two characters to build a story around. One of them I named Tommy, a man with some connection to the house and the other one, the house itself.

Anchoring the story in the present, and keeping it there made the crux of the film the revelation of the two characters, Tommy and the house. But a question persisted. What would I be revealing? This question was answered when I decided to give each character a secret, and make the revelation of these secrets the thrust of the story.

The secret I gave the house would the terrible fire that had destroyed its foundations and a family who had made the once sturdy walls of the house their home. For Tommy, his secret would be found on his head, where a hideous scar covered exactly one half of his face. The first step towards developing my “iceberg approach” was complete. I had defined what would be hidden (the 90%) and what would be seen (the 10%). The next step would be to develop a strategy of dramatizing the revelation of the secret each of these two characters harbored in a way that would give the viewer a sense of the bigger picture. I needed to make the viewer see the whole iceberg when I could only show its tip.

The two pieces that make up the cinematic puzzle are sound and picture. They form the overall experience a viewer has when watching a film. So, I decided to use these two elements to reveal my characters in stages.

Think of it like this. Someone is standing in front of you, but with their back turned. They turn ninety degrees, so now you see them in a profile. They turn another ninety degrees, facing you. Three positions; back, profile, and front.

Since there are two polar opposites when it comes to shot sizes in cinematography, the wide and the close-up, I decided to film one of each, the wide to minimize visual information and the close-up to maximize it, for each position. Two shot sizes times three positions equals six shots.

Throughout the film the viewer sees these shots, interspersed with other ones, in the following order as the story unfolds.

1. WS of man (back turned to camera, face not visible)

2. CU of man (back to camera, up close)

3. WS of man (profile, the side of his face with no scar, but from a distance)

4. CU of man (same profile up close).

5. WS of man (he faces the camera, but from a distance)

6. CU of man (we see his whole face for the first time, up close)

This directorial strategy allowed me to perform the symbolic action of turning the Tommy character from unseen (back facing us) to seen (front facing us) in a way that is interwoven in the cinematography. He is revealed to us in incremental stages. The CU of Tommy’s face, the last shot in his shot arc, reveals Tommy’s secret, his scar. This gives that arc a satisfying payoff, because the preceding shots have been given a purpose.

For the house, I followed the same approach. I used two props to slowly reveal the horrifying history of the house. One was a burnt doll and the other, the second to last shot of the film, was four crucifixes stuck in the ground outside the house. After Tommy’s disfigured face is revealed, he walks away, and a pan of the camera reveals the crucifixes.

I added sound to give this revelation more depth. Before the shot of the crucifixes, there is a shot that shows wind jostling around tree branches outside the house. I married the sound of the wind with the sound of roaring flames to make a seamless transition towards the film’s climax, a shot of Tommy with a gun to his head, ready to pull the trigger.

In conclusion, exposition is a powerful tool in a film. This project gave me a stronger understanding of how that tool, despite the limitations of a small budget, can be used to suggest conflict in a compelling way.

The Seen (2016) will premiere at the Rosebud Film Festival on January 28th, 2017.