Sign up for the

TSL Newsletter

and get $50 off Final Draft 12

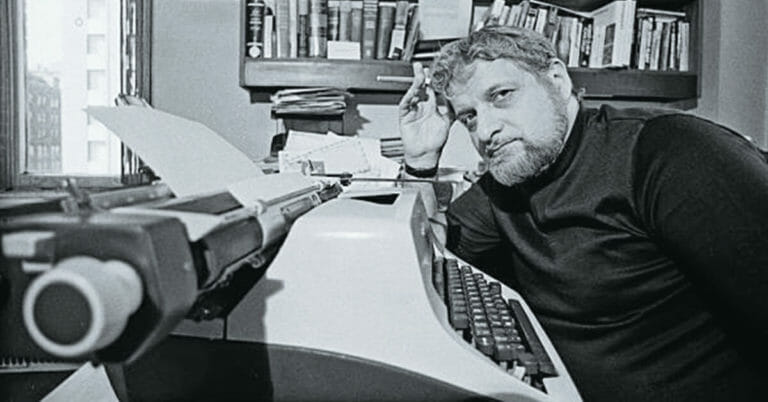

By Martin Keady · February 28, 2018

It is often said that the early 21st century is “the golden age” of television, with remarkable shows such as The Wire, The Sopranos and Mad Men enabling TV finally to cast off any supposed inferiority in relation to its artistic big brother, cinema. Indeed, it is often argued that the greatest screenwriting now is not for cinema but for television, and even that cinema has become a medium for children while television is the only place to find genuinely “adult” (as in grown-up and complex, rather than pornographic) ideas and themes being explored.

As always, the truth is more complicated than that. There have been great television shows and series since the extraordinary expansion in television from the 1950s onwards. Consequently, Martin Keady, our resident screenwriting historian and author of The Great Screenwriters Series, is now turning his attention to television and looking at the life and work of those writers who made the supposedly “small screen” truly epic in scale, in a new series entitled The Great Television Writers.

In the future, he will look at writers as brilliant and diverse as David Simon, Dennis Potter, Sharon Horgan and Carla Lane. But in the first part of the series, he examines the career of the man who was arguably the very first great writer for television, Paddy Chayefsky.

Paddy Chayefsky was not a “Paddy” (as in, an Irishman) at all. Like so many of the greatest screenwriters, for both film and television, he was Jewish and specifically Jewish of Eastern European descent (his family hailing from Ukraine). Apparently, Sidney Aaron Chayefsky earned his unusual nickname during his time in the US Army at the end of World War II. Realising that if he attended religious services, such as a Catholic mass, he would be excused the mundane kitchen duties that he loathed, he soon claimed to be attending services several times a day, to the point that his comrades christened him “Paddy”, on the basis that he must have been Irish to go to church so often. The nickname stuck and so “Paddy Chayefsky” eventually became that rarest of things, a New York Jewish writer with a “green” (or Irish) streak running through him. As a gag-man himself at the start of his career, Chayefsky would have appreciated the irony and the image that his name presented, that of a Jewish man who also loved a drop of Guinness or Murphy’s.

Paddy Chayefsky was not a “Paddy” (as in, an Irishman) at all. Like so many of the greatest screenwriters, for both film and television, he was Jewish and specifically Jewish of Eastern European descent (his family hailing from Ukraine). Apparently, Sidney Aaron Chayefsky earned his unusual nickname during his time in the US Army at the end of World War II. Realising that if he attended religious services, such as a Catholic mass, he would be excused the mundane kitchen duties that he loathed, he soon claimed to be attending services several times a day, to the point that his comrades christened him “Paddy”, on the basis that he must have been Irish to go to church so often. The nickname stuck and so “Paddy Chayefsky” eventually became that rarest of things, a New York Jewish writer with a “green” (or Irish) streak running through him. As a gag-man himself at the start of his career, Chayefsky would have appreciated the irony and the image that his name presented, that of a Jewish man who also loved a drop of Guinness or Murphy’s.

Chayefsky had been born in The Bronx in 1923 and his early life and education were similar to those of so many Jewish writers of his generation, in that he began writing in high school (writing for and editing the school magazine) and eventually studied at a public university, the City College of New York. However, unlike most writers, he was a talented athlete as well as an assiduous scholar, so much so that he played American football (or gridiron) as a semi-professional for a local New York team, Kingsbridge Trojans.

Chayefsky entered the US Army in time for the final onslaught on Nazi-occupied Western Europe. He was obviously an extremely brave soldier, to the extent that he was awarded a Purple Heart, for conspicuous bravery. It was the first major award that he had ever received, but in time he would be able to put Academy Awards and other prestigious prizes for writing alongside it in the display cabinet.

It was the injury Chayefsky sustained while on military duty that really made him a writer. While he was recuperating in a hospital in England, he somehow found the time and the energy to write a musical, Say No T.O. for Love (1945). Fittingly, it was first performed by the US Special Services Unit (the entertainment wing of the military), who took it to US bases across Europe, and then performed professionally in London’s West End at the Scala Theatre. Chayefsky found some other writing work in Europe, including on a US army documentary called The True Glory. However, he could not find enough work to sustain him in post-war Britain and he duly returned to New York after the war.

It was the injury Chayefsky sustained while on military duty that really made him a writer. While he was recuperating in a hospital in England, he somehow found the time and the energy to write a musical, Say No T.O. for Love (1945). Fittingly, it was first performed by the US Special Services Unit (the entertainment wing of the military), who took it to US bases across Europe, and then performed professionally in London’s West End at the Scala Theatre. Chayefsky found some other writing work in Europe, including on a US army documentary called The True Glory. However, he could not find enough work to sustain him in post-war Britain and he duly returned to New York after the war.

Rather like Jay Gatz – The Great Gatsby – Chayefsky must have wondered if the war, in which he had not only fought so bravely as a soldier but found work as a writer, was all a dream. Like Gatsby, who returned to America and relative poverty after World War I, Chayefsky had to go back to working in the printer’s shop run by his uncle after his service in World War II. However, in true “Chayefskian” style (and ultimately there would be a distinctive Chayefskian style), he used the hard work and mundane, repetitive life of a printer as the inspiration for another play, Printer’s Measure (1953). Even more importantly, it became the basis for his first screenplay, As Young As You Feel (1951). As Young As You Feel was the story of an elderly printer who, facing compulsory retirement on the grounds of age, dyes his grey hair black and pretends to be a much younger man. At this early point in his career, Chayefsky was not even the screenwriter as such (he was only credited with “story by”) and the film is largely unmemorable, other than being one of the first films that a young Marilyn Monroe appeared in. Nevertheless, Chayefsky had his first screenwriting credit and like most aspiring East Coast-based playwrights and scriptwriters in the early to mid-20th century, he soon headed west to Hollywood.

However, unlike so many other New York Jewish writers, from Ben Hecht to the Epstein brothers, Chayefsky did not immediately hit pay-dirt in Los Angeles. Indeed, he often joked that the only thing he had ever found in Hollywood was his wife, Susan, who he married in 1949. Having failed to find any long-term employment as a writer, he eventually returned to New York and worked in the family businesses, as he had done before on returning from Europe, and contemplated how on earth he could find full-time work as a writer.

However, unlike so many other New York Jewish writers, from Ben Hecht to the Epstein brothers, Chayefsky did not immediately hit pay-dirt in Los Angeles. Indeed, he often joked that the only thing he had ever found in Hollywood was his wife, Susan, who he married in 1949. Having failed to find any long-term employment as a writer, he eventually returned to New York and worked in the family businesses, as he had done before on returning from Europe, and contemplated how on earth he could find full-time work as a writer.

Fortunately for Chayefsky, the new medium of television was beginning to take hold of the American consciousness and would in time capture the global consciousness. Although television had been invented nearly a quarter of a century earlier in 1927, when Britain’s John Logie Baird first transmitted images of a face between London and Glasgow, it had very much remained the runt of the artistic litter for the first few decades of its existence. However, in the consumer and baby boom that followed World War II, television suddenly became a mass market medium, rather than an elite one, and consequently, there was growing demand for “new content”, in exactly the same way that there is now for new online material.

Chayefsky’s first scripts for television were for series such as Danger, a murder-mystery (or whodunit) drama that was most notable for being produced live, as if it were a stage production. This was commonplace for television in America in the early 1950s and it led to a demand for proven scriptwriters, such as Chayefsky, who initially learned about the opportunities provided by the new medium and then began to impose their own vision upon it.

Chayefsky’s first scripts for television were for series such as Danger, a murder-mystery (or whodunit) drama that was most notable for being produced live, as if it were a stage production. This was commonplace for television in America in the early 1950s and it led to a demand for proven scriptwriters, such as Chayefsky, who initially learned about the opportunities provided by the new medium and then began to impose their own vision upon it.

Chayefsky continued to submit scripts to series such as Philco (The Philco Television Playhouse) and it was for that series that he produced his first televisual masterpiece, Marty (1953). Like the episodes of Danger, it was performed live, but rather than being about cops and robbers or cowboys and “Indians”, it was about ordinary American people. The titular Marty was a butcher from Chayefsky’s own New York neighborhood, The Bronx, who sought love but, lacking obvious looks and charm, despaired of ever finding it. As Chayefsky said of the story after it became his “breakout” success, it was “the most ordinary love story in the world”. Unwittingly, however, he had identified the one quality that would ultimately most distinguish television from cinema, namely the sheer ordinariness of its stories and characters. Whereas Hollywood remained the reserve of the rich and powerful, and therefore told extraordinary tales about extraordinary people (some of which were actually based on fairy tales), television offered the opportunity to examine the everyday, the quotidian and the apparently un-romantic. And from its first staging, Marty, embodied all these qualities, striking a chord in the US psyche and setting it apart from so many other unmemorable television dramas of the time.

The title character of Marty was first played on television by a young Rod Steiger, but when it was subsequently remade as a film the part went to Ernest Borgnine, who ultimately became synonymous with it. The success of Chayefsky’s script, both on TV and then on film, was the making of him, especially when he won an Academy Award (for Best Adapted Screenplay) for the film.

Marty was such a success that it almost became the template for other television dramas, not only in America in the 1950s America but far beyond in both space and time. Indeed, one of the best British television films ever made (and like Marty it was shown both in the cinema and on TV), Ballroom of Romance (1982), was almost a remake of Marty, or rather a relocation of the story from the Bronx to rural Ireland.

After Marty, Chayefsky finally had not only the income he had always dreamed of earning from writing but the influence to get more of his own ideas realized. And if nothing he wrote could quite match the impact of Marty, which is now generally regarded as the first great TV drama written and produced anywhere, he was still able to contribute regularly to the kind of “anthology” series, in which a different story in a different genre (comedy, romance, drama) was told each week, that had become so popular on American television by the mid-1950s.

In addition to his writing for television, which provided him with a stable source of income as a writer for the first time, Chayefsky was able to maintain a prodigious output for those media that he had already written for, including stage and cinema. Indeed, often his work began on television before enjoying a second life on stage and film. A classic example was Middle of the Night (1954), which was similar to Marty in being the seemingly innocuous tale of a young secretary who is visited at home by her much older boss, who is a widower. In Chayefsky’s expert hands, however, it soon developed into a gripping drama, as the secretary and boss fall in love, much to the disapproval of their respective friends and families. Middle of the Night was a great success in all three media – television, stage and film – culminating in a 1959 cinema version that was nominated for the Palme D’Or, with the Cannes Film Festival proving an unusually glamorous setting for such a defiantly unglamorous tale.

Chayefsky continued to write for stage and screen (both TV and cinema screens) and his major works in the 1960s included The Latent Heterosexual, a play, and a co-writing credit on the screen adaptation of a musical, Paint Your Wagon (also 1969). However, he would have to wait until the 1970s to enjoy a second wave of success to go alongside his triumphs of the mid-1950s.

The first of Chayefsky’s 1970s masterpieces was The Hospital (1971), which was almost his Citizen Kane, in that he wrote, produced and narrated it (although Arthur Hiller directed it). Starring George C. Scott as a doctor experiencing a mid-life crisis, The Hospital, although written directly for cinema, was comparable to the best of Chayefsky’s 1950s TV work, such as Marty and Middle of the Night, in that it focused on the everyday, almost hum-drum workings of a major hospital, which none the less faces a series of crises, including the deaths of doctors and the building of a rehabilitation clinic for drug and alcohol addiction, which inevitably prompts protests against it from the people who live nearby. As with Marty more than 15 years earlier, The Hospital represented a new direction in screen writing, in which what someone did (their everyday work) was as important – indeed, it was often indistinguishable from – their own personal identity. That was borne out at the end of the film, as George C. Scott’s doctor has to forego the romantic love he has dreamed of to try and keep the hospital he has built from going under. Once again, as with Marty, Chayefsky won an Academy Award, this time for Best Original Screenplay, and once again his writing stock was high.

Chayefsky’s next major work was probably his greatest work of all and also his most emblematic, in that it was a screenplay for a feature film but one based on the medium that Chayefsky had first thrived in, television. Since the 1950s, when Chayefsky had mainly written for the medium, television had almost literally exploded, to the point where it had become (and arguably remains) the most important visual medium. The film was Network (1976) and it was the story of Howard Beale, a TV news presenter who suddenly “goes rogue” and starts commenting on the news, rather than just reading it. To his astonishment and that of his producers, he becomes a media sensation, with his catch-phrase, “I’m as mad as hell and I’m not going to take this anymore!”, becoming almost a mantra for millions of other disaffected citizens in mid-1970s America, when – post-Vietnam and post-OPEC price hikes – America seemed, for the first time in its history, to be going backward rather than forward.

Network was a huge commercial and critical hit. It was nominated for numerous Academy Awards and won four, including Best Original Screenplay for Chayefsky. Thus it completed a remarkable hat-trick for Chayefsky, who remains the only writer to have won three individual Academy Awards for Writing, with the other three-time winners, such as Woody Allen and Billy Wilder, being only co-writers of their award-winning scripts. Even more importantly, the film continues to have a remarkable “after-life”, particularly in the age of Trump and Brexit, when seemingly the entire western world (or at least large parts of the British and American electorates) are also proclaiming that they’re “Mad as Hell” and determined to do something about it. That probably accounts for Network’s recent return to the zeitgeist in the early 21st century, with a stage adaptation of the screenplay, starring Breaking Bad’s Bryan Cranston, currently playing at The National Theatre in London, and a new book about the making of the film, Mad as Hell by Dave Itzkoff, having just been released. In effect, the perhaps psychotic Howard Beale has become one of the great spokespeople of our age.

Chayefsky continued to write post-Network, notably Altered States (1980), based on his own novel of the same name, which told the story of a writer who undergoes a series of psychiatric tests to examine the influence upon his consciousness of various drugs, including LSD and mescaline. Apparently, Chayefsky had conducted a lot of “personal” research for the book, which both exhausted him and arguably took him away from the type of stories that he excelled at, namely ones that were more obviously ordinary than obviously extraordinary, and focused on ordinary butchers and bankers rather than on writers suffering from seemingly self-inflicted madness. Ultimately, Chayefsky felt that the film adaptation of his novel was unsatisfactory, so much so that he had his author’s name – Paddy Chayefsky – removed from the credit and instead (in what may be a first in the history of cinema) had his real name, or at least his real first name and middle name, “Sidney Aaron”, inserted instead.

Chayefsky died in 1981, not long after the release of Altered States, when he was still only 58, and it is a shame that one of the last acts of such a great writer was to have his name removed from the credits of a movie he had written. Nevertheless, in documenting the seemingly “small” dramas of American life in the mid-1950s, and then examining the absurdity of television’s impact upon the world in Network in the 1970s, he assured that he was not only the first great writer of television but arguably the writer whose name will most remain synonymous with television in the future.

Martin Keady is an award-winning scriptwriter whose work has been produced for film, television, stage and radio. His major credits include: The Final, a short film about the famous ending of the 1979 FA Cup Final, which was shown on Channel Four; Moon the Loon, a play about the legendary Who drummer, Keith Moon, which was premiered at The Edinburgh Festival; and a collection of love poetry, Shards, extracts from which have been broadcast on Radio Four.” http://theshakespeareplays.com/

Martin Keady is an award-winning scriptwriter whose work has been produced for film, television, stage and radio. His major credits include: The Final, a short film about the famous ending of the 1979 FA Cup Final, which was shown on Channel Four; Moon the Loon, a play about the legendary Who drummer, Keith Moon, which was premiered at The Edinburgh Festival; and a collection of love poetry, Shards, extracts from which have been broadcast on Radio Four.” http://theshakespeareplays.com/

Photos courtesy of gettyimages.com.

For all the latest from The Script Lab, be sure to follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.