By Andrew Schwartz · April 2, 2018

2018’s Oscar nominations for Best Adapted and Original Screenplays featured another compelling set of characters brought to life through dynamic performances. Inspired by The Hollywood Reporter’s recent post, we’re delving deeper into the collaborative effort of filmmaking to see how screenplays are translated from script to screen. Let’s dive in!

Saoirse Ronan embodies Lady Bird so perfectly that it’s almost impossible to think of anyone else performing in that role. But Greta Gerwig didn’t write the part with her in mind; she didn’t write it with anyone in mind.

Sam Levy & Greta Gerwig during the filming of “Ladybird.”

At A24’s Lady Bird Cast Official Q&A panel, Greta Gerwig expressed this saying; “when I wrote [Lady Bird], I was trying to create a person who was more brave than I had the ability to be; who was more wildly herself; and it wasn’t until I saw Saoirse do it that I felt like I got to meet this flawed heroine who I felt I had made up.”

“On the page, you can instantly see the battles we have,” says Laurie Metcalf, also in attendance at the panel, “but I love the little moments of heart that are thrown here and there that go a long way in telling the backstory.”

The opening scene is a good example of this; the tension is in the script, but it’s accelerated by the overlapping dialogue and nuanced subtleties of their exchange.

Some things are better left unsaid… or completely changed — Jordan Peele wrote the script for Get Out about eight years before it was released, and while certain aspects of the script remained true to their original form, the film found its stride well after the screenplay was finished. Peele has frequently stated that many things, including the ending and various plot points, were changed to better align with the themes of the films as it progressed.

In the THR article, Peele cites a rewrite so crucial that not changing it could have jeopardized the film. He spoke further in a Vanity Fair Reddit Q&A about omitting a line of Walter the Groundskeeper’s dialogue for being too over the top. Think back to the scene of the brother, Jeremy, playing the ukulele disconcertingly; another moment that was created on set.

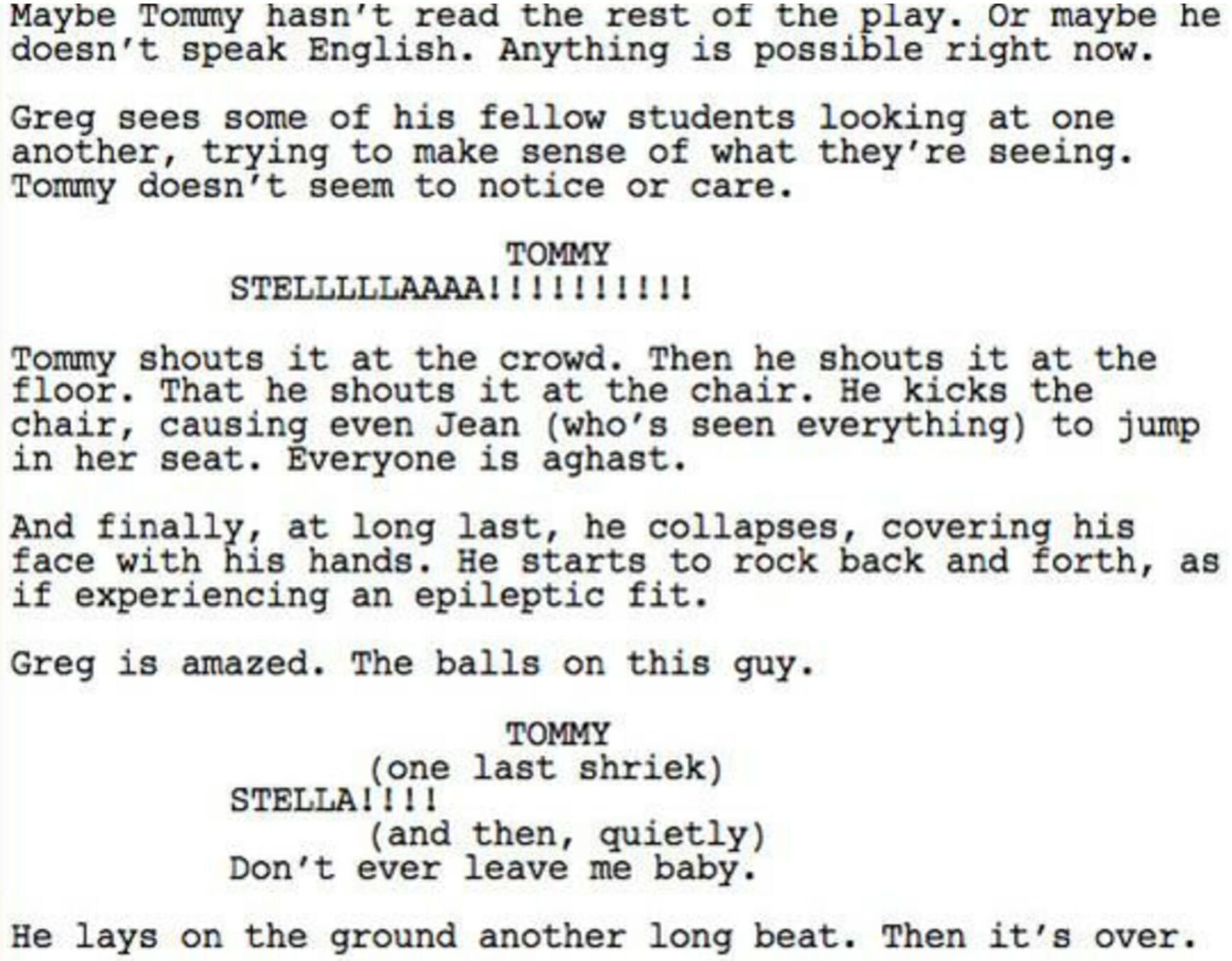

The Disaster Artist – the Oscar-nominated film about the worst movie ever made. When writing the script, the writers focused heavily on creating a character who is compelling and comedic while both sad and antagonistic – not an easy feat.

James Franco on the set of The Disaster Artist.

Featured in a recent Entertainment Weekly article, writers Scott Neustadter and Michael H. Weber discussed bringing Tommy Wiseau to life by occasionally dialing back on what was originally written and letting the actors take the lead. The result was a larger-than-life portrayal by James Franco who took literal leaps and bounds in bringing Tommy Wiseau to the screen.

Below is an excerpt from the opening pages of the script – Franco kicked the chair, yes, but he also threw that chair, climbed the walls of the rehearsal space and fell on his ass a few times. “We didn’t really know how that would come across until we saw the scene happen and how James brought some real heart to it,” says Weber.

The Big Sick

The Big SickEmily V. Gordon and Kumail Nanjiani wrote The Big Sick based on their personal experiences, but the film’s magic came from the nuanced performances of the characters they crafted for the screen.”It’s so hard to show people falling in love,” says Nanjiani in an article published on the Writers Guild of America, East’s website, “[audiences] buy it; they don’t necessarily feel it.”

Tasked with creating on-screen versions of themselves, Gordon and Nanjiani relied heavily on the input of people removed from their relationship – director Michael Showalter in particular – to help develop the film in a dynamic and engaging way. Nanjiani says, “[Showalter] really adjusted the performances so that you could see the negotiation that happens between two people.”

If the audience couldn’t believe in Kumail and Emily’s relationship in the film’s set-up, the rest of the story wouldn’t have worked. The writing, directing and acting exist in perfect harmony leaving a finished product that feels as real as it does relatable.

There are so many great things that can be said about The Shape of Water, which was nominated for 13 Academy Awards and won four, including Best Picture. Guillermo del Toro has attributed the film’s success to the characters that brought the eclectic story to life on the screen. “A really great actor can be wrong for a part,” claims del Toro in an article recently published by Variety, but Doug Jones (Amphibian Man) and Sally Hawkins (Elisa Esposito) brought subtle complexities to their respective roles in ways that truly showcase the power of performance.

Jones and Hawkins had the particularly challenging endeavor of portraying the love between a deaf woman and a hybrid human/fish creature. How’d they do it? Glenn Whipp of the LA Times writes,

“[Jones and Hawkins] took dance lessons, learning each other’s body movements as well as establishing a foundation of trust. They laughed and cried, shared secrets about their insecurities so that when the time came to portray characters who not only fall in love but save each other’s lives, they were ready.”

See how the film takes its shape from the script below;

The Oscars ceremony ends with The Best Picture Award (Shape of Water), but a film will always begin with the script. With a little help from their actor and director friends, the writers nominated for Best Adapted (James Ivory for Call Me By Your Name) or Original Screenplay (Jordan Peele for Get Out) brought their characters to life from script to screen in ways that went way beyond the page. In doing so, they made their characters human; they made them real.

For all the latest from The Script Lab, be sure to follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

Photo credit: A24 via ABC News