By Martin Keady · July 21, 2018

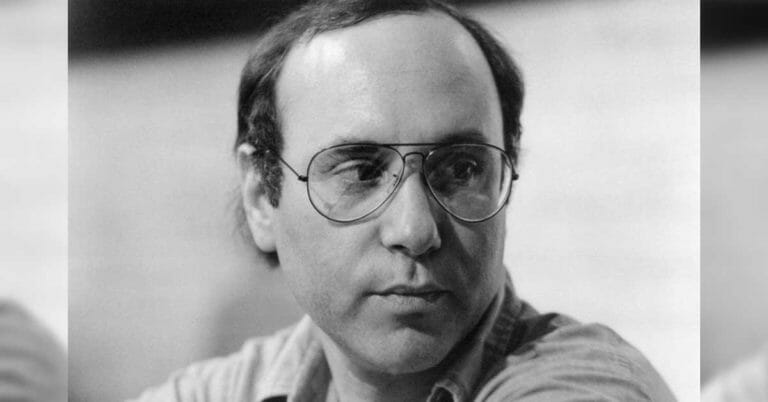

There are great screenwriters and then there are great co-screenwriters. Like Charles Brackett and I.A.L. Diamond (Billy Wilder’s two great writing partners), Marshall Brickman falls into the second category, having achieved far greater success as Woody Allen’s co-screenwriter than he ever did as a screenwriter in his own right. Nevertheless, like Brackett and Diamond before him, he merits inclusion in any consideration of great cinema writers, principally because his two finest co-writes – Annie Hall and Manhattan – are not only Woody Allen’s two greatest films but two of the greatest films ever made.  Like Woody Allen and so many other of the great screenwriters of the 20th century, Marshall Brickman was Jewish. However, unlike Allen and so many other great screenwriters, he hailed not from New York but from Rio de Janeiro. He was born there in 1939, the son of an American couple (Abram and Pauline) who had moved to Brazil to live and work. Given that World War Two broke out soon after his parents’ arrival in South America, there must have been times later in his life when Marshall was grateful that his parents had emigrated. Although the US was not bombed during World War Two (other than at Pearl Harbor, of course), life in America during wartime was still far more tense and fraught than it would have been in Rio. Indeed, for a brief period (roughly between 1940 and 1955), life in Brazil, at least for the foreign expatriates there, was something of a gilded existence.

Like Woody Allen and so many other of the great screenwriters of the 20th century, Marshall Brickman was Jewish. However, unlike Allen and so many other great screenwriters, he hailed not from New York but from Rio de Janeiro. He was born there in 1939, the son of an American couple (Abram and Pauline) who had moved to Brazil to live and work. Given that World War Two broke out soon after his parents’ arrival in South America, there must have been times later in his life when Marshall was grateful that his parents had emigrated. Although the US was not bombed during World War Two (other than at Pearl Harbor, of course), life in America during wartime was still far more tense and fraught than it would have been in Rio. Indeed, for a brief period (roughly between 1940 and 1955), life in Brazil, at least for the foreign expatriates there, was something of a gilded existence.

After his sun-kissed childhood, Brickman attended college in the US, studying at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He began his studies there in the late 1950s, at the end of the Eisenhower era, which again was a period of relative peace and prosperity, at least in comparison with war-torn Europe, which was still struggling to recover from the destruction wrought upon it by the Nazis. However, as the 1960s began, Brickman completed his education and was ready to take his first tentative steps as what would now probably be called a “creative” (an anodyne, almost meaningless term used to refer to anyone working, or trying to work, in the arts). Brickman did not begin as a writer. Instead, like so many Western teenagers at that time, he became a musician, singing in a folk group called The Terriers, which was most notable for also featuring Eric Weissberg. Weissberg was a hugely gifted banjo player who would go on to write the most famous banjo song ever written, “Duelling Banjos”, which would become a gigantic hit a decade later as the soundtrack to Deliverance (1972). After The Terriers broke up in the mid-1960s, Brickman continued in music, joining a group whose name is worthy of inclusion in the script of Spinal Tap, because “The New Journeymen” is almost as bad as the name used for the first iteration of The Tap, “The New Originals”. However, despite their dubious nomenclature, The New Journeymen also contained future musical stars, namely John Phillips and Michelle Phillips, who would go on to become half of The Mamas & the Papas.

Brickman did not begin as a writer. Instead, like so many Western teenagers at that time, he became a musician, singing in a folk group called The Terriers, which was most notable for also featuring Eric Weissberg. Weissberg was a hugely gifted banjo player who would go on to write the most famous banjo song ever written, “Duelling Banjos”, which would become a gigantic hit a decade later as the soundtrack to Deliverance (1972). After The Terriers broke up in the mid-1960s, Brickman continued in music, joining a group whose name is worthy of inclusion in the script of Spinal Tap, because “The New Journeymen” is almost as bad as the name used for the first iteration of The Tap, “The New Originals”. However, despite their dubious nomenclature, The New Journeymen also contained future musical stars, namely John Phillips and Michelle Phillips, who would go on to become half of The Mamas & the Papas.

Brickman himself would not attain fame and fortune as a musician. Instead, he abandoned music (at least professionally) in the late 1960s and became a writer for television, specifically a gag and sketch writer for shows such as Candid Camera and The Dick Cavett show. More than a decade earlier, Woody Allen had begun his own extraordinary career by writing for television shows such as The Ed Sullivan Show and The Tonight Show, and he too had contributed to Candid Camera. Both Brickman and Allen later attributed much of their success as writers to their early “schooling” in television. Nevertheless, they also experienced the frustrations inherent in simply writing jokes and short sketches rather than anything longer or more substantial. Consequently, it is no coincidence that the Woody Allen character in Manhattan, Isaac Davis, is a writer who has abandoned television to try and write a novel. Brickman met Allen when the latter had already abandoned his own television writing career to try and fulfill his lifelong ambition of making movies. There were considerable differences between the two men. Allen, by his own admission, was the archetypal New York Jew, who had always written for a living, whereas Brickman, by virtue of his upbringing in Brazil, was far more cosmopolitan and had semi-successfully pursued a career in music before becoming a writer. Nevertheless, they hit it off, realizing that they shared not only a common ethnicity and religion but a similar sense of humor, and in the early 1970s they became writing partners.

Brickman met Allen when the latter had already abandoned his own television writing career to try and fulfill his lifelong ambition of making movies. There were considerable differences between the two men. Allen, by his own admission, was the archetypal New York Jew, who had always written for a living, whereas Brickman, by virtue of his upbringing in Brazil, was far more cosmopolitan and had semi-successfully pursued a career in music before becoming a writer. Nevertheless, they hit it off, realizing that they shared not only a common ethnicity and religion but a similar sense of humor, and in the early 1970s they became writing partners.

Allen himself refers to his first forays into film as “the early, funny ones”. Indeed, he was to satirize his fans’ obsession with those broad but laugh-out-loud comedies in Stardust Memories (1980), in which a successful film-maker (played by Allen) struggles to make more serious movies because his audience only wants to laugh. (Even visiting aliens ask him why he stopped being funny.) However, those early cinematic efforts remain outstandingly funny today, and one of the finest of them all is Sleeper (1973), which Allen co-wrote with Brickman. Sleeper is a wonderful spoof of the wonderful sci-fi movies of the late 1960s and early 1970s (the golden age, or at least the first golden age, of sci-fi cinema), such as 2001 and Planet of the Apes (both 1968), and Soylent Green (1973). Allen plays his typical klutz or nebbish character, but instead of being transported to modern-day South America, as in Bananas (1971), or to 19th-century Russia, as in Love and Death (1975), he is “frozen” (without his permission) in the then present day and wakes up in the future. Typically for Woody, he inadvertently becomes part of a rebellion against the ruling dictator, which culminates in his abduction of all that survives of the dictator after an assassination attempt – namely, his nose.

Sleeper is a wonderful spoof of the wonderful sci-fi movies of the late 1960s and early 1970s (the golden age, or at least the first golden age, of sci-fi cinema), such as 2001 and Planet of the Apes (both 1968), and Soylent Green (1973). Allen plays his typical klutz or nebbish character, but instead of being transported to modern-day South America, as in Bananas (1971), or to 19th-century Russia, as in Love and Death (1975), he is “frozen” (without his permission) in the then present day and wakes up in the future. Typically for Woody, he inadvertently becomes part of a rebellion against the ruling dictator, which culminates in his abduction of all that survives of the dictator after an assassination attempt – namely, his nose.

Sleeper is still blissfully funny today, but it was very much of its time in Woody Allen’s career, namely that early and outright funny period. As with any co-write, it is impossible to determine the exact nature and scale of Brickman’s contribution to its script. However, given his own background in gag-writing, it is probable that he at least came up with a number of the jokes (especially given the fact that there are hundreds of jokes in the movie). But what is really fascinating is what happened next. Although Allen would go on to make another “early, funny” movie (the aforementioned Love and Death), which he wrote on his own, when it finally became time for him to mature as a film-maker and make a film that was not simply comic but a beautiful, even unique combination of drama and comedy, he returned to his earlier co-writer, Brickman, to help him.  Annie Hall (1977) is, without doubt, the greatest film that Woody Allen has ever made and probably the only one that even his many detractors would admit to smiling at. Once again, Allen effectively plays himself, or more specifically a less financially and romantically successful version of himself, Alvy Singer. Alvy recounts, direct to camera (at least to begin with), the story of the love of his life, Annie Hall, and especially the end of their love affair. Annie Hall is that rarity in cinema, an almost genreless film, or perhaps it is its own genre. It is certainly funny, but it is also profoundly moving, addressing the deep-seated fears and feelings of inadequacy that exist in almost all of us but which so many supposedly “romantic comedies” fail even to acknowledge, let alone address. It combines fantastic jokes, sight gags, animation, skits, stand-up sketches and almost everything else that Allen possessed in his comic arsenal. And for good measure, it must also have contained a large measure of its co-writer, Marshall Brickman.

Annie Hall (1977) is, without doubt, the greatest film that Woody Allen has ever made and probably the only one that even his many detractors would admit to smiling at. Once again, Allen effectively plays himself, or more specifically a less financially and romantically successful version of himself, Alvy Singer. Alvy recounts, direct to camera (at least to begin with), the story of the love of his life, Annie Hall, and especially the end of their love affair. Annie Hall is that rarity in cinema, an almost genreless film, or perhaps it is its own genre. It is certainly funny, but it is also profoundly moving, addressing the deep-seated fears and feelings of inadequacy that exist in almost all of us but which so many supposedly “romantic comedies” fail even to acknowledge, let alone address. It combines fantastic jokes, sight gags, animation, skits, stand-up sketches and almost everything else that Allen possessed in his comic arsenal. And for good measure, it must also have contained a large measure of its co-writer, Marshall Brickman. As with most great movies, the making of Annie Hall has itself become legendary, and that legend is perhaps best recorded in the seminal book on cinematic editing written by its editor, Ralph Rosenblum, When the Shooting Stops, the Cutting Begins: A Film Editor’s Story. Rosenblum edited many films, but it is his work on Annie Hall that is most famous, largely because of his account of it in the book. He explains that so dizzying was the invention (especially the comic invention) of both Allen and Brickman that the film became almost impossible to contain within a two-hour window. Consequently, it had to be re-created (or perhaps really created for the first time) in the editing studio, where Rosenblum, with the assistance of Allen and Brickman, painstakingly pieced the film together until it finally made sense – or at least as much sense as a film about the total senselessness of life can muster.

As with most great movies, the making of Annie Hall has itself become legendary, and that legend is perhaps best recorded in the seminal book on cinematic editing written by its editor, Ralph Rosenblum, When the Shooting Stops, the Cutting Begins: A Film Editor’s Story. Rosenblum edited many films, but it is his work on Annie Hall that is most famous, largely because of his account of it in the book. He explains that so dizzying was the invention (especially the comic invention) of both Allen and Brickman that the film became almost impossible to contain within a two-hour window. Consequently, it had to be re-created (or perhaps really created for the first time) in the editing studio, where Rosenblum, with the assistance of Allen and Brickman, painstakingly pieced the film together until it finally made sense – or at least as much sense as a film about the total senselessness of life can muster.

Despite its difficult gestation and the fact that it was Allen’s first ever “serious” movie, Annie Hall was a tremendous success, both commercially and critically. It won Allen and Brickman the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay, which is entirely appropriate, given that it is arguably the most original screenplay ever written, at least for a supposedly “mainstream” movie.

Allen’s next film, Interiors (1978), seemed to undo much of the good work of Annie Hall, in being a self-consciously dramatic piece (even didactically so) about three siblings who are all struggling to make their way in the world. Compared to Annie Hall, it was a flop, although Allen would return to the “three siblings” theme far more successfully nearly a decade later in Hannah and Her Sisters (1986). Back in 1978, however, as he struggled to cope with the relative failure of Interiors after the spectacular success of Annie Hall, he decided that the best move that he could make was to work again with Brickman. The result was the film that is almost certainly Allen’s second greatest movie, Manhattan (1979). In this series on screenwriters, I have often used the boxing analogy of the “one-two punch”, the classic combination of strikes provided by a writer’s best two movies, especially if those two movies are startlingly different. In the entire history of cinema, it is arguable that there has never been a better “one-two punch” than that of Annie Hall and Manhattan. Both films may have been written by Allen and Brickman together, and both films may feature Allen himself playing a character who is at least outwardly similar to himself, but other than that they are very different. Most obviously, Annie Hall was shot in color and Manhattan is black and white. Far more importantly, where Annie Hall was astonishingly formally inventive (which of course made it so difficult to piece together in the editing studio), Manhattan is self-consciously classical, a deliberate attempt by Allen (aided by Brickman) to make a contemporary film as powerful, moving and plain beautiful as those that the two men had adored when they were growing up. And they triumphantly succeeded.

In this series on screenwriters, I have often used the boxing analogy of the “one-two punch”, the classic combination of strikes provided by a writer’s best two movies, especially if those two movies are startlingly different. In the entire history of cinema, it is arguable that there has never been a better “one-two punch” than that of Annie Hall and Manhattan. Both films may have been written by Allen and Brickman together, and both films may feature Allen himself playing a character who is at least outwardly similar to himself, but other than that they are very different. Most obviously, Annie Hall was shot in color and Manhattan is black and white. Far more importantly, where Annie Hall was astonishingly formally inventive (which of course made it so difficult to piece together in the editing studio), Manhattan is self-consciously classical, a deliberate attempt by Allen (aided by Brickman) to make a contemporary film as powerful, moving and plain beautiful as those that the two men had adored when they were growing up. And they triumphantly succeeded.

Manhattan was not the breakout success that Annie Hall had been; that was impossible as, by definition, an artist can only achieve “breakout success” once in their career. Nevertheless, it was still a superbly written account of another love affair that goes wrong. However, whereas Annie Hall was the story of a love affair between two mixed-up but still supposedly mature adults, Manhattan was the story of a much more imbalanced affair, between Allen’s forty-something writer and his 17-year-old girlfriend, Tracy (memorably played by Mariel Hemingway). It was contentious enough at the time, but in the wake of the child abuse allegations made against Allen by Mia Farrow when their relationship ended the early 1990s it has become, for many people, almost unwatchable. Whatever the ethical and moral quandaries the film presents, it is still an incredible piece of film-making, less obviously dazzling than Annie Hall but arguably even more heartfelt. The great critic, Pauline Kael, famously said of Manhattan that it was so beautiful that it made you forget the dogshit you encountered everywhere in the real New York. As with Annie Hall, it is absolutely impossible, especially four decades on, to establish the precise scale and nature of the contribution that Marshall Brickman made to Manhattan as its co-writer. What is unarguable, however, is that Allen’s two finest screenplays were both co-written with Brickman, and that has to be more than coincidental. It is possible that Brickman, more worldly and laconic than Allen, counterbalanced Allen’s obvious neurosis and nerdiness, to create a worldview that is more complex and more balanced than that presented in many other Woody Allen films, especially the ones that he wrote himself.

As with Annie Hall, it is absolutely impossible, especially four decades on, to establish the precise scale and nature of the contribution that Marshall Brickman made to Manhattan as its co-writer. What is unarguable, however, is that Allen’s two finest screenplays were both co-written with Brickman, and that has to be more than coincidental. It is possible that Brickman, more worldly and laconic than Allen, counterbalanced Allen’s obvious neurosis and nerdiness, to create a worldview that is more complex and more balanced than that presented in many other Woody Allen films, especially the ones that he wrote himself.  Such was the success of their co-writing on Annie Hall and Manhattan that it is remarkable that Allen and Brickman did not write another film together for 14 years, which was Manhattan Murder Mystery (1993). Indeed, although it was made in the 1990s, the idea for Manhattan Murder Mystery was first developed in the late 1970s/early 1980s, when Allen and Brickman were regular writing partners. As has often been said, the only thing that Manhattan Murder Mystery has in common with Manhattan is the word “Manhattan”. Other than that, the latter film, which is the story of an ordinary New York couple (again played by Allen and Diane Keaton, his muse on Annie Hall) who find themselves involved with and eventually investigating a murder case, is entirely typical of the many mediocre films that Allen has made in the last two decades, with notable exceptions such as Deconstructing Harry (1998) and perhaps his final sublime masterpiece Midnight in Paris (2011).

Such was the success of their co-writing on Annie Hall and Manhattan that it is remarkable that Allen and Brickman did not write another film together for 14 years, which was Manhattan Murder Mystery (1993). Indeed, although it was made in the 1990s, the idea for Manhattan Murder Mystery was first developed in the late 1970s/early 1980s, when Allen and Brickman were regular writing partners. As has often been said, the only thing that Manhattan Murder Mystery has in common with Manhattan is the word “Manhattan”. Other than that, the latter film, which is the story of an ordinary New York couple (again played by Allen and Diane Keaton, his muse on Annie Hall) who find themselves involved with and eventually investigating a murder case, is entirely typical of the many mediocre films that Allen has made in the last two decades, with notable exceptions such as Deconstructing Harry (1998) and perhaps his final sublime masterpiece Midnight in Paris (2011).

Nevertheless, even such late-period Woody Allen films do not quite match the sheer comic and cinematic mastery of Annie Hall and Manhattan. Those two films alone, two of only four that Allen and Brickman wrote together in more than 20 years, are enough to guarantee both men cinematic immortality.

Martin Keady is an award-winning scriptwriter whose work has been produced for film, television, stage and radio. His major credits include: The Final, a short film about the famous ending of the 1979 FA Cup Final, which was shown on Channel Four; Moon the Loon, a play about the legendary Who drummer, Keith Moon, which was premiered at The Edinburgh Festival; and a collection of love poetry, Shards, extracts from which have been broadcast on Radio Four.” http://theshakespeareplays.com/

Martin Keady is an award-winning scriptwriter whose work has been produced for film, television, stage and radio. His major credits include: The Final, a short film about the famous ending of the 1979 FA Cup Final, which was shown on Channel Four; Moon the Loon, a play about the legendary Who drummer, Keith Moon, which was premiered at The Edinburgh Festival; and a collection of love poetry, Shards, extracts from which have been broadcast on Radio Four.” http://theshakespeareplays.com/

Images from The Know, WAMC, Collider and Rolling Stone.

For all the latest from The Script Lab, be sure to follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.