By Martin Keady · November 29, 2018

The death of the Miloš Forman earlier this year was a reminder of how great so many of his films were, from The Firemen’s Ball (1967) to Amadeus (1984) to The People vs. Larry Flynt (1996). His greatest film, which is arguably the greatest film ever made about mental illness (and specifically the often harrowing reality of mental institutions), is One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975), which was written by Robert “Bo” Goldman. Goldman is the other great screenwriter with that surname, the first being William Goldman, who also recently passed away, writer of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969), All The President’s Men (1976) and probably the greatest book ever written on screenwriting, Adventures In The Screen Trade (1983). Perhaps that is why “Bo” Goldman does not enjoy the fame he should as the writer of several cinematic masterpieces, including the aforementioned Cuckoo’s Nest, Melvin and Howard (1980) and Shoot The Moon (1982).

Goldman, like his more famous namesake William and many other great American screenwriters, was born in New York (in 1932) and grew up there. The family business was fashion, not film. His mother, Lillian, had been a model and his father, Julian, owned a number of department stores known simply as The Goldman Stores. However, Julian used some of the money he made from his department stores to finance his real passion, which was Broadway theatre. He supported many shows financially and loved the theatre so much that he went to it at least twice a week, often taking Robert with him and thus inculcating in his son a lifelong love of theatre, which is the medium in which Robert began his scriptwriting career.

Robert, or “Bo” as he was nicknamed from an early age, pursued his interest in theatre while studying at Princeton. Indeed, so sophisticated and successful were his productions (some of which he wrote for) that one of them, the punningly titled Ham ‘n’ Legs, ended up on national television in 1953, as part of the legendary The Ed Sullivan Show, the variety show that would effectively launch The Beatles in America a decade later. However, Goldman was unable to capitalize on his student success immediately as he had to complete his national service, which, rather incredibly, was mostly spent on the Marshall Islands in the Pacific Ocean, one of the early sites for American nuclear testing.

Goldman survived the obvious dangers of serving his country near a nuclear test site and returned to America in the mid-1950s, determined to follow his own (and his father’s) dream of making it as a writer on Broadway. His first foray was called, appropriately enough, First Impressions and was a musical version of Pride and Prejudice, for which he wrote the lyrics. However, First Impressions did not create many lasting impressions and soon closed. Undeterred, Goldman tried to write and produce a play about the American Civil War, called Hurrah Boys Hurrah, but there was no last or even first “hurrah” for it as it never reached Broadway.

As he slunk away from Broadway in the late 1950s, it is entirely likely that Goldman felt that he had not only let himself down but his father, who had always loved the theatre. However, he was now married with a young family and so made the decision to pursue his writing and producing career in the newest of the narrative art forms, television. He may have begun by trading on memories of his youthful success on The Ed Sullivan Show but he was soon able to build a substantial and successful career. He gained his first writing credit on a 1958 TV adaptation of The Paradine Case (1947), a courtroom drama that had originally been a Hitchcock film, and then, even more impressively, he was a producer and script editor on the original TV version of Days of Wine and Roses, which would be remade for cinema in 1962.

He worked on several of the “Playhouse” series that were immensely popular on American television in the 1950s and 1960s, adapting plays or short stories for television. Days of Wine and Roses was originally part of the Playhouse 90 strand and Goldman eventually moved on to the public television version, NET Playhouse. It was there that he met Burt Lancaster, a Hollywood legend reduced to “slumming it for TV”, as working in television was often regarded before the current golden age of TV in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Goldman has always said that it was Lancaster who first encouraged him to try his hand at screenwriting and although he was not immediately commercially successful, Goldman soon hit artistic paydirt with Shoot The Moon, a divorce drama that was initially his calling card script but would eventually become one of his finest films. Most importantly, however, it brought him to the attention of Miloš Forman, who was so impressed by it that he ended up hiring Goldman, at the time an unknown screenwriter, to help adapt Ken Kesey’s 1962 novel, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, for the screen. Goldman was paired with Lawrence Hauben, another inexperienced screenwriter, and few in the film industry at the time, other than Forman, had any faith that this co-writing team of unknowns would be a success.

The novel, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, had been written more than a decade earlier by, Ken Kesey, the novelist and poet who became the embodiment of the 1960s counter-culture; indeed, Cuckoo’s Nest itself was based on his own experiences of working in a mental hospital for military veterans. Although the book was an immediate critical and commercial success, and was adapted for the stage within a year, it was also thought to be almost “unfilmable”, as it was narrated in the first person by “Chief”, a giant but apparently mute Native American.

In adapting the book for the screen, Goldman and Hauben retained “Chief” (who would eventually become the only “cuckoo” to escape the “nest”), but effectively made him a supporting character to Randle P. McMurphy, the petty criminal who pretends to be mad to get himself transferred to a mental hospital from prison, in the belief that it will be a much cushier number. He is, of course, completely mistaken and as he discovers the reality of the institution he has arrived in – where the patients are largely sedated rather than treated – he tries to fight back, ironically by attempting to convince his captors and doctors that he is sane after all. All of this is witnessed by “Chief”, who becomes the viewer’s eyes as we witness the final, tragic triumph of the system over McMurphy and the final, glorious escape of “Chief” himself.

Measured solely by the Academy Awards that it won, Cuckoo’s Nest was the most successful film in more than forty years, as it was the first film since It Happened One Night in 1934 to win all of the five most important Oscars: Best Picture; Best Actor in a Lead Role (for Jack Nicholson, as McMurphy); Best Actress in a Lead Role (for Louise Fletcher, as McMurphy’s nemesis, Nurse Ratched); Best Director (for Forman); and Best Screenplay (for Goldman and Hauben). Extraordinarily, Hauben would not write or co-write another major film again, but for Goldman, it was the beginning of an imperial purple patch in which he would write some of the most successful and iconic films of the 1970s and ‘80s.

For his next major screenplay, Goldman was again paired with another writer, Bill Kerby, whose main writing credit was the Burt Reynolds stuntman movie, Hooper (1977). Goldman and Kerby wrote the most thinly veiled of thinly veiled biographies about Janis Joplin, which was originally called Pearl, after the tragic singer’s last album. However, when Joplin’s family refused to sign over the rights to her story, it was renamed The Rose (1979). Nevertheless, it was clearly inspired by and modeled on Joplin’s troubled life and career, and with Bette Midler whooping it up in her first starring role, The Rose was a considerable hit, even if, unlike Cuckoo’s Nest, it was not nominated for many awards.

Goldman’s next film script was the first that he wrote solo and so he alone can take credit for the wondrous weirdness of Melvin and Howard (1980). It was based on the extraordinary true story of Melvin Dummar, a gas (or petrol) station owner who becomes the major beneficiary of Howard Hughes, the famously reclusive billionaire, after he helps Hughes to recover from a motorcycle accident. Melvin thinks little of it, until the discovery of a handwritten will by Hughes reveals the identity of the man he had helped and the extraordinary reward that he will receive.

Howard Hughes is such an iconic and quintessentially American figure that films by and about him virtually constitute a sub-genre of their own, from Hell’s Angels (1930), the WWI aerial epic that he directed, to The Aviator (2004), Martin Scorsese’s truly epic biopic, which is probably the greatest film that Scorsese has made in his second great period of film-making from 2000 onwards. And yet arguably the film that is closest to capturing the sheer craziness of Hughes, the world’s most famous OCD sufferer, is Melvin and Howard, even though it is not so much about him as the effect he has on others, including Melvin, his unlikely beneficiary.

Goldman won another Screenwriting Oscar for Melvin and Howard, an achievement that effectively put him in a class of his own as a screenwriter, as he had now won an Oscar for Best Original Screenplay on his own to go alongside the Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay that he had won with Lawrence Hauben for Cuckoo’s Nest. More specifically, he was regarded as the “Master of Madness”, the writer who could best write seemingly insane stories about seemingly insane people.

Such was Goldman’s success, and more importantly his “bankability”, that he was now able to get his “calling card” script Shoot The Moon, which he had originally written more than a decade earlier, into production. And so Shoot The Moon became the third part (after Cuckoo’s Nest and Melvin and Howard) of what might be called Goldman’s “Insanity” Trilogy. However, in Shoot The Moon he was not writing about the inmates of an asylum or a famous (and famously) rich madman. Instead, his subject matter was the everyday and often unnoticed madness of divorce.

Shoot The Moon (1982) might be the best film you’ve never heard of – a relatively little-known classic. Perhaps its subject matter – the painful, often agonizing reality of divorce – has prevented it from becoming more well-known, but that really should not be the case. Quite simply, it is probably the best film about divorce ever made and a far better film than many more famous “divorce” movies, such as Kramer vs. Kramer (1979).

Goldman had begun writing Shoot The Moon in 1971 and he spent much of the rest of the 1970s desperately trying to get it made. Finally, at the start of the next decade, when he was armed with not one but two Academy Awards for Screenwriting, he was finally able to achieve his ambition. Alan Parker, who at the time was in the middle of his own extraordinary streak of successful films, which began with Bugsy Malone (1976) and ended with The Commitments (1991), learned of the script while he was making Fame (1980) and was immediately entranced by its depiction of the “bitter-bitter” (as opposed to bitter-sweet) reality of marital breakdown. And of course in the decade since Goldman had first written Shoot The Moon, divorce rates around the world, including in America, had increased almost exponentially, making the film and its story even more relevant and resonant.

Shoot The Moon is the story of a couple (played by Albert Finney and Diane Keaton) who go from an apparently happy marriage to one of the most unhappy marriages ever captured on screen, especially when they both try to form new relationships with other people even though they remain almost umbilically linked together. It is a spectacular script, both erudite and imagistic (with its memorable title coming from a move in a card game); it might be Alan Parker’s very best film; and the reviews were the kind that writers dream of writing themselves, including raves by the likes of Vincent Canby and Gene Siskel. And yet it died in the cinemas, apparently because of a clause in Keaton’s contract that prevented the release of another film starring her within a year of the release of Reds (1981), the drama about the Russian revolution in which she starred alongside Beatty. As a result, the release of Shoot The Moon was delayed, it never regained momentum and became a “box-office” flop even though it was an artistic triumph.

Arguably, Bo Goldman’s screenwriting career, which in less than a decade had won him two Academy Awards, never fully recovered from the commercial failure of his beloved pet project. He continued to write films, the most successful of which was Scent of a Woman (1992), another hit but hardly in the artistic class of Cuckoo’s Nest and Shoot The Moon. Indeed, such was his increasing frustration with film-making that after an uncredited rewrite of The Perfect Storm (2000) he did not write another screenplay for more than 15 years.

That script, the last that Goldman has written to date, was for Rules Don’t Apply (2016). Rules Don’t Apply is a fairly unremarkable film and thus is emblematic of much of Goldman’s late-period writing. However, it is fascinating for two reasons: first, because it was directed by Warren Beatty, the man who more than a quarter of a century earlier had effectively stymied Shoot The Moon; and, secondly, because it is the story of an actress and chauffeur in late 1950s Hollywood whose burgeoning love affair is prohibited by their jealous, insecure employer, one Howard Hughes. So, at the end of his screenwriting career, as at the start of it, Goldman has returned to the dominant theme of his very best films, namely insanity. Although Rules Don’t Apply does not bear comparison with Cuckoo’s Nest and Shoot The Moon, it is a reminder that for much of the late 20th century the greatest chronicler of madness in the movies was Bo Goldman, a sane man in a largely insane industry.

Martin Keady is an award-winning scriptwriter whose work has been produced for film, television, stage and radio. His major credits include: The Final, a short film about the famous ending of the 1979 FA Cup Final, which was shown on Channel Four; Moon the Loon, a play about the legendary Who drummer, Keith Moon, which was premiered at The Edinburgh Festival; and a collection of love poetry, Shards, extracts from which have been broadcast on Radio Four.” http://theshakespeareplays.com/

Martin Keady is an award-winning scriptwriter whose work has been produced for film, television, stage and radio. His major credits include: The Final, a short film about the famous ending of the 1979 FA Cup Final, which was shown on Channel Four; Moon the Loon, a play about the legendary Who drummer, Keith Moon, which was premiered at The Edinburgh Festival; and a collection of love poetry, Shards, extracts from which have been broadcast on Radio Four.” http://theshakespeareplays.com/

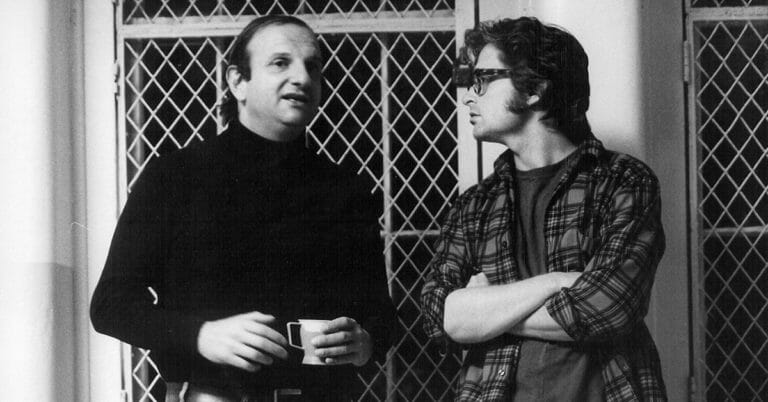

Photo: Bo Goldman and Michael Douglas while working on One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest

For all the latest from The Script Lab, be sure to follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.