By Shanee Edwards · October 8, 2018

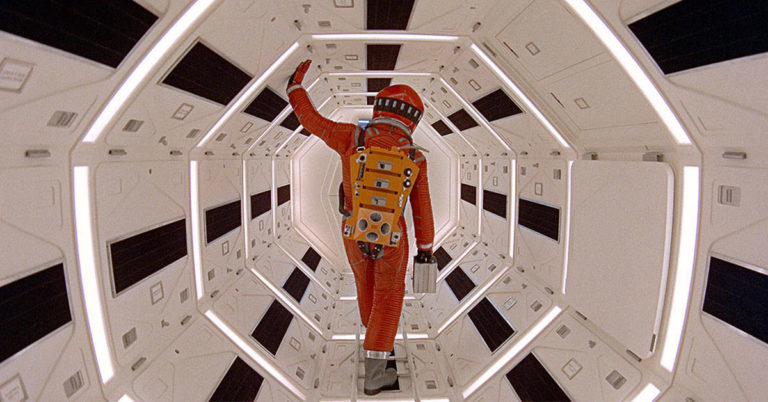

It’s hard to believe that 2001: A Space Odyssey is 50 this year. Regarded as one of the best science fiction films of all time, this space opera has had five decades to become irrelevant, outdated and laughable – but it hasn’t. Surprisingly, it remains a powerful statement on the relationship between humanity and technology while raising questions about the mystery of the universe.

Even as artificial intelligence becomes a reality, as cars drive themselves, as we plan a trip to Mars, writer/director Stanley Kubrick, along with writer Arthur C. Clarke, imagined a futuristic world that still rings true all these years later. As screenwriters in the sci-fi genre, we can learn quite a bit from looking at the film from a writer’s perspective. Here are the seven biggest takeaways.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, first published in 1818, a time in which electricity was widely being explored, is said to have birthed the sci-fi genre. Frankenstein continues to be remade over and over, suggesting that audiences love to question man’s ability to play God. Electricity has since fueled humanity’s quest to develop weapons, alter our own bodies and explore the universe. There are endless sci-fi stories to be told. As a screenwriter, take a look at your fears. For Kubrick, his fear was nuclear weapons, and rightfully so. The 1960s was the height of the Cold War. While nuclear weapons still remain a threat, we are facing new threats like climate change, national security threats from computer hackers and the weaponization of Artificial Intelligence. Think about what keeps you up at night and write about that – it could make for a powerful screenplay.

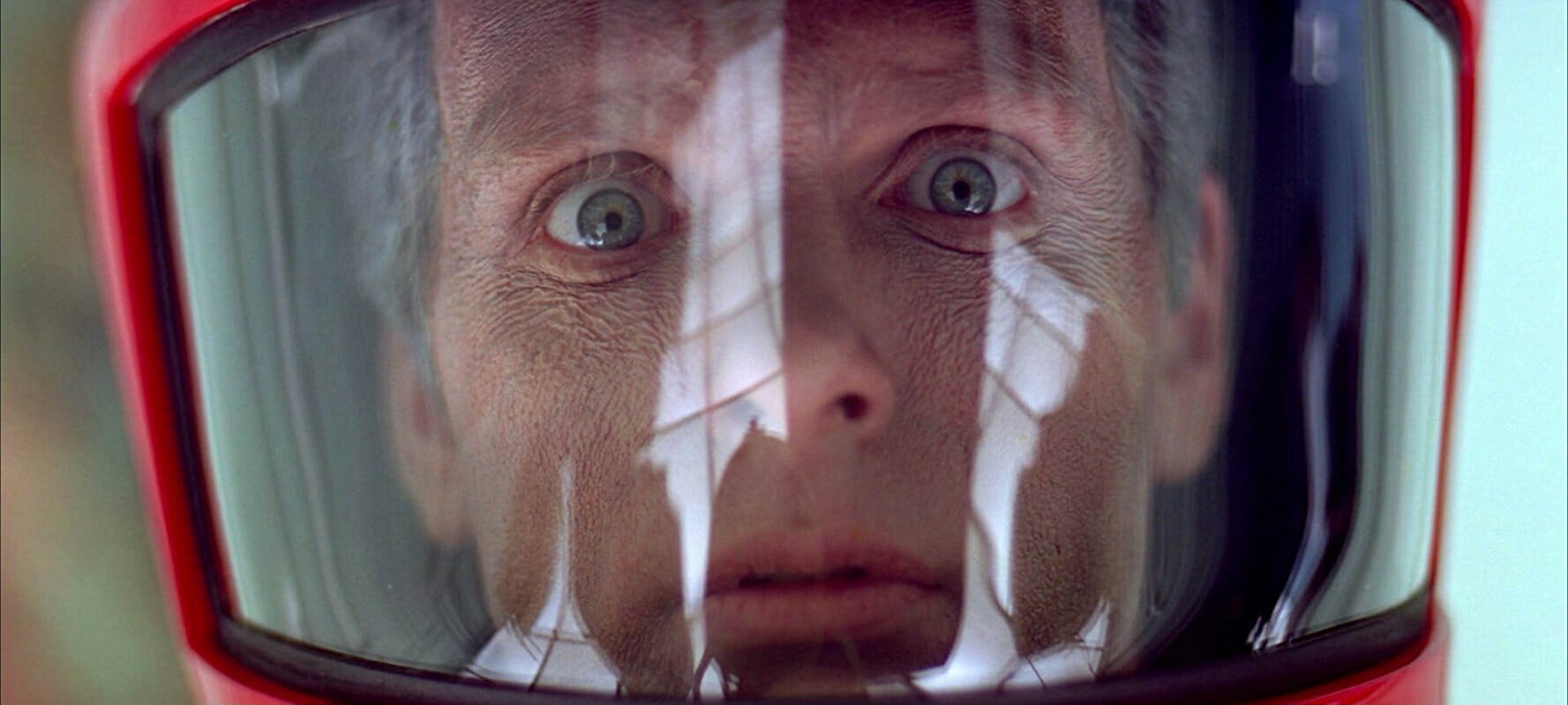

There are roughly 88 minutes in 2001 that have no dialogue at all, making it an excellent example of “show, don’t tell.” The main characters have very limited dialogue and are restrained emotionally, making room for plenty of subtext. Some good rules for minimizing dialogue are as follows: If the character is using several sentences to get his point across, see if you can make the point in one sentence. Then, see if that one sentence can be reduced to one word. Then determine if that one word can be reduced to a look or an action.

Instead of using a computerized voice, H.A.L. 9000 is voiced by a human, Douglas Rain. Many people think H.A.L. shows more emotion and anguish than any of the other human characters. This is a smart choice, because it takes away the “otherness” or cold, mechanical nature of a robot. The more human it sounds, the more frightening it is. Think about ways to humanize technology in your own screenplays for a less conventional choice.

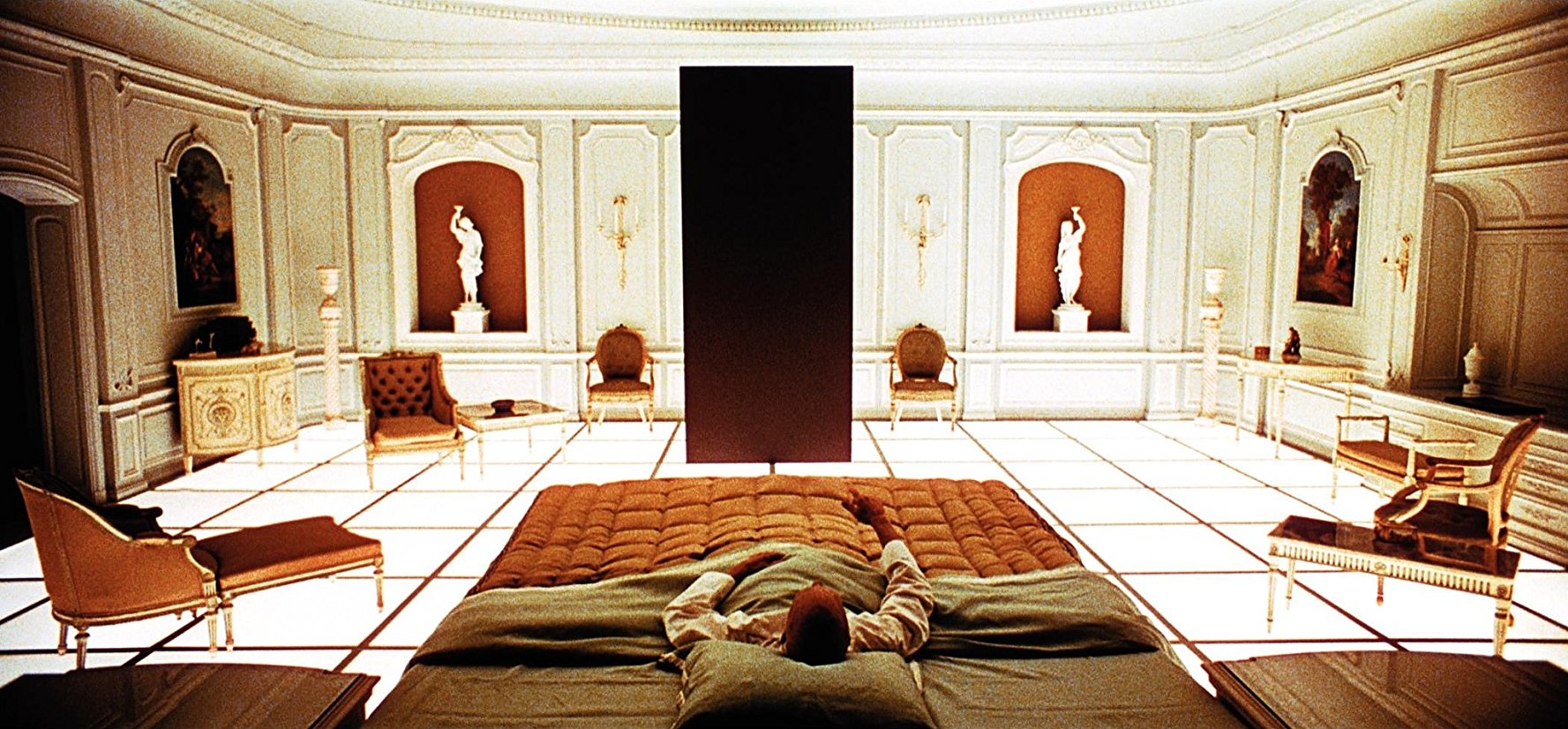

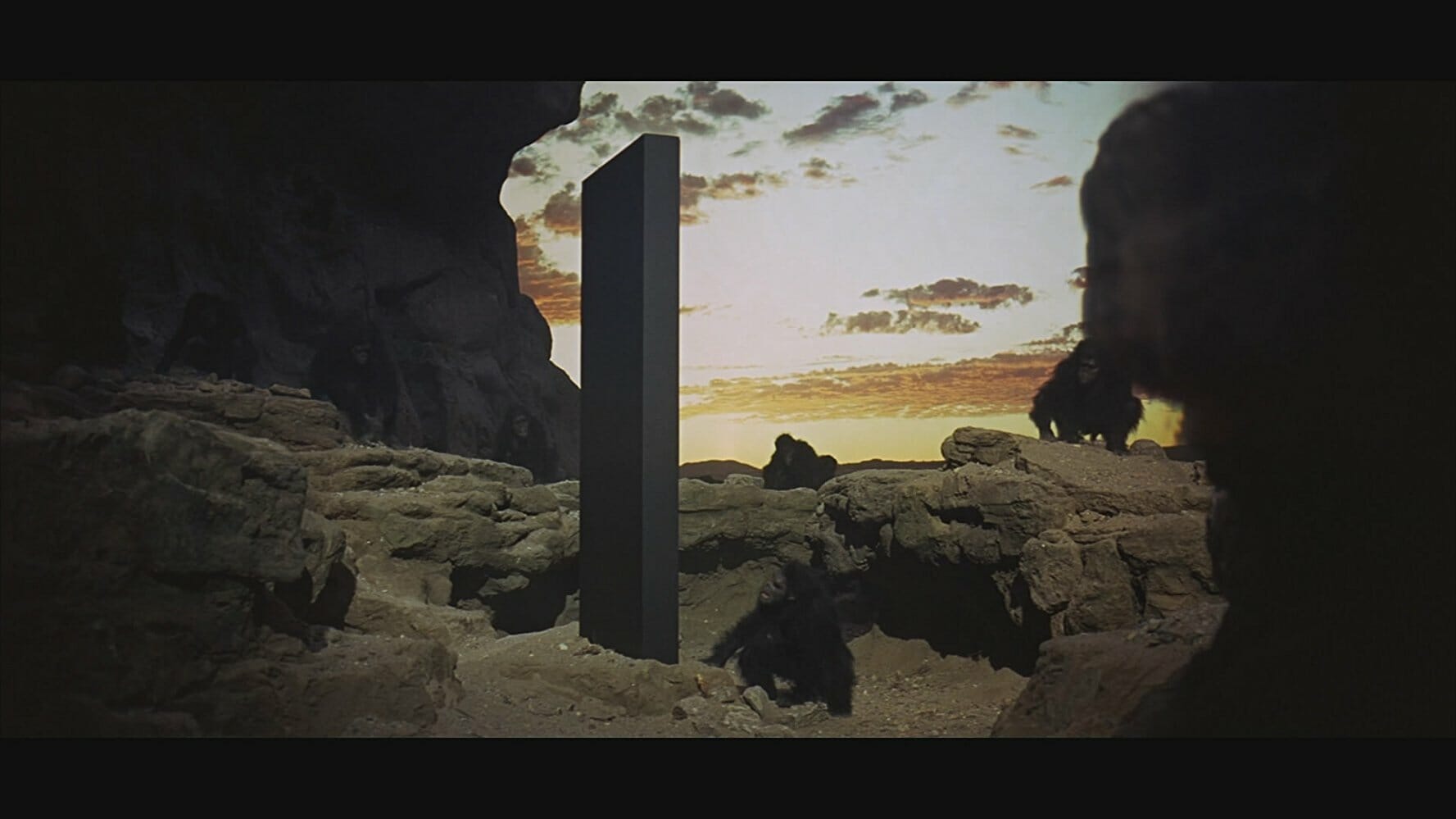

Though the monoliths are never fully explained in the film, they are an excellent visual representation of the great mystery of the universe, or possibly even God. The monoliths give us a sense that something intelligent came before us and is perhaps watching or monitoring us. On a deeper level, they represent our own higher consciousness, overseeing our own personal evolution. The monoliths clearly inspired the giant pod in Arrival (2016). Think about exciting ways to visually represent the unknown in your own screenplay. Do you use an iconic symbol like a monolith or is your sense of mystery embodied in physical powers like The Force in Star Wars? In Blade Runner (1982) it’s the Tyrell Corporation that seems to be in charge of orchestrating life and death. Decide what works for your story.

Most sci-fi films are scored with original music to help guide the audience’s emotions, helping them know when to be scared, when to be excited, etc. Though Kubrick had hired to film composer Alex North to score 2001, he chose instead not to score most of the film and include classical music like “Also sprach Zarathustra” composed in 1896 by Richard Strauss. The result is that there is a timeless quality to the film. Though most screenwriters don’t end up with control over the music, you can use this example as inspiration for how you connect the past to the future in your sci-fi script.

After making Dr. Strangelove: or How I Stopped Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), Kubrick wanted to make a film that explored the possibility of the existence of alien life, so he decided to collaborate with sci-fi novelist, Arthur C. Clarke. Though Kubrick fired Clarke (but then rehired him), Clarke brought a deep understanding of the genre and also had many connections to people in the aerospace industry who could be useful as consultants. The famous astrophysicist Carl Sagan was also a consultant on the film and guided Kubrick away from having human actors portray aliens because life on other planets would not have evolved the way humans did. The lesson here? If you’re not an expert on something, reach out to one. You’d be surprised how many university professors or other professionals would be willing to chat. I once enticed a group of geneticists at UCLA with Sprinkles cupcakes. They answered all my questions.

In the original draft of the screenplay, the monolith was discovered in the third act. As Kubrick and Clarke mulled over the story, they decided to set it up from the start. The monolith became the inciting incident for the story when one is discovered buried on our moon sending signals toward Jupiter. Sometimes, a good idea needs to be finessed and shifted around. Use index cards to write down all the big moments and turning points in your story and feel free to move them around to help spark ideas for changing the structure.

Shanee Edwards graduated from UCLA Film School with an MFA in Screenwriting and is currently the film critic for SheKnows.com. She recently won the Next MacGyver television writing competition to create a TV show about a female engineer. Her pilot, Ada and the Machine, is currently in development with America Ferrera’s Take Fountain Productions. You can follow her on Twitter: @ShaneeEdwards

Shanee Edwards graduated from UCLA Film School with an MFA in Screenwriting and is currently the film critic for SheKnows.com. She recently won the Next MacGyver television writing competition to create a TV show about a female engineer. Her pilot, Ada and the Machine, is currently in development with America Ferrera’s Take Fountain Productions. You can follow her on Twitter: @ShaneeEdwards

More sources: https://www.cnet.com/news/2001-a-space-odyssey-michael-benson-book-review/ and http://blog.zoominfo.com/the-top-5-business-lessons-from-2001-a-space-odyssey/

For all the latest from The Script Lab, be sure to follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.