By Richard Walter · October 6, 2015

Even though I’m a screenwriter and film educator I rarely read movie reviews.

Here and there I may peek at a review, but never one that treats a movie I have not yet seen.

My reluctance is not because, like everybody else, I loathe spoilers.

It is based instead upon the principle that if a reviewer loves a film, I’m likely to find it disappointing.

Conversely, if a critic hates a film, I’ll probably consider it worthy.

This is testimony to the power of expectations.

High expectations? The film disappoints.

Low expectations? The movie is better than anticipated.

Many critics seem to laud almost any film that fails at the box office. This feeds their narcissism by demonstrating how intelligent, insightful, astute, and profoundly intellectual they are (and how dense, how blind, how stupid everyone else is).

Likewise, critics denounce almost any film that enjoys blockbuster commercial success. The critic’s already fragile ego – who in her right mind would set out to be a critic; isn’t ‘movie critic’ just a fall-back position for one who couldn’t make it in show business? — is soothed by a sense of superiority, a feeling that the critic belongs to an artistic and creative club: an elite.

A better word: snobs.

My favorite film critic was my grandmother.

She was no snob.

I recall two informal reviews she gave a pair of movies I happened to see with her and my sister Jessica at a neighborhood theater in Jackson Heights, Queens, when we were kids.

I don’t remember the names of the movies, but they were released in the early ‘50s, two black and white WWII air force epics. Perhaps one was God Is My Copilot.

In those days when movies played in neighborhood theaters they were inevitably part of a double bill, that is, two movies for the price of one.

And there was much more than merely two movies.

There were also cartoons, newsreels, a ‘short subject’ or two or three, maybe a travelogue, and always previews of coming attractions.

Notably, it was the custom in that era for patrons never to check the screening schedule in advance. Audiences would routinely enter at their convenience in the middle of one movie, sit through it until the end, then view all the in-between paraphernalia, and then watch the entire second film, which was followed by still more interim material, and finally the first movie again, this time from the beginning, remaining until the film came around to the point where they had entered.

On that particular occasion maybe sixty years ago at The Earle Theater on Northern Boulevard, the second picture might have been Twelve O’Clock High.

During this ordeal, if they had carried Dramamine at the popcorn stand, they would have made a fortune.

We sat there through hour after hour of soaring, roaring engines, dog fights, bombing runs, anti-aircraft fire, hearing crackling dialogue like “Jap Zero on your tail at oh-four-hundred hours!” and worse.

In the intermission, the newsreels ran still more black and white Air Force footage, this time reporting on battles from the bloodbath de jour, the Korean War.

By the time the first film came around again and reached the point where we had entered, my sister and I rose from our seats and headed for the aisle.

Grandma said, “Where are you going?”

We said, “This is where we came in.”

With an Eastern European inflection as thick as borscht, Granny said, “But I thought there were two pictures.”

Years later, with Jessie herself a star of stage and screen, she was not so much at the movies as in the movies,

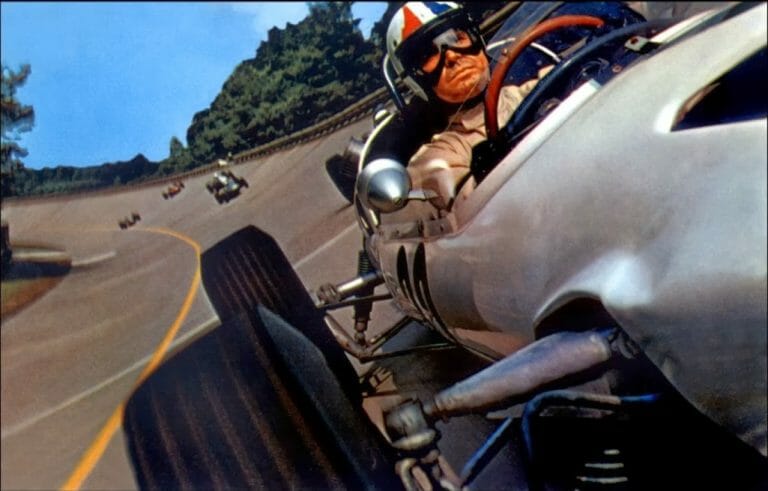

My girlfriend (and now longtime bride) and I went along with a passel of friends and family (including my favorite film critic) to the world premiere of a movie in which Jess starred opposite James Garner, the international racing epic Grand Prix.

It was not unusual during that era for movies to run long, at least in their original release. (By the time they hit the neighborhood houses they might have been trimmed so as to fit the platform for the double feature.)

When movies ran as long as Grand Prix, they also had an intermission.

Of course the actors gave splendid performances, but the whole evening seemed to take about as long as the Bronze Age.

After enduring the entire film, including the intermission, in the lobby my date turned to my grandmother and asked, “What did you think of the movie?”

Granny shrugged, rolled her eyes, adjusted her dress, sighed, and said, “I should have worn the other girdle.”

About the Author:

Richard Walter is a celebrated storytelling guru, movie industry expert, and longtime chairman of UCLA’s legendary graduate program in screenwriting. A screenwriter and author of bestselling fiction and nonfiction, Professor Walter’s latest book is Essentials of Screenwriting. The newly released Mandarin language edition tops the list of film books on Amazon’s China site. Professor Walter lectures and conducts master classes throughout North America and the world. He is a sought-after script doctor in Hollywood and also a court authorized expert in intellectual property litigation. For more information and to order his book visit www.richardwalter.com. Contact Professor Walter at [email protected] if you would like to subscribe to his monthly screenwriting tips newsletter.

Richard Walter Copyright © 2015