By Martin Keady · January 11, 2021

Screenwriting is often team-writing – a collaboration between two or more writers on a single film or television series. Indeed, perhaps there is something unique about screenwriting that lends itself to the relentless back-and-forthing of writers working together to come up with ideas, sketch out storylines (or even loglines and concepts) and above all generate naturalistic and memorable dialogue.

It is certainly far harder to think of great writing teams in other genres of writing, such as fiction, poetry or even playwriting, than it is to think of great screenwriting teams. In fact, co-writing seems to have existed from the very start of cinema in the late 19th century, particularly with the French brothers Méliès (Georges and Gastons), and the Lumières (Auguste and Louis), the sibling writers who created so many of the first films, including, most famously, A Trip to the Moon (Le Voyage dans la Lune) in 1902. They may not have thought of their joint devising of ideas and storylines as screenwriting, let alone team-writing, but in effect that is what it was.

Of course, the basic co-writing team is usually the director and the screenwriter of a film working together, often to rewrite the first draft of the script that the screenwriter has usually produced on their own. There are numerous examples of such director-writer teams from cinema history, including: Powell and Pressburger, who apparently could not work together in the same room and had to write separately; the Coen Brothers, who began their career by dividing credit over direction (Joel) and production (Ethan) but always wrote together; and even Orson Welles and Herman J. Mankiewicz, whose precise contributions to the writing of Citizen Kane have been disputed ever since Kane first appeared, a process that continues right up to the present day with the favourite for this year’s Best Picture Oscar, Mank. Speaking of — for a great interview with the producer of Mank, check out: Five Lessons For Filmmakers From Producer Doug Urbanski

However, the very greatest screenwriting teams, not just in terms of quantity but in terms of quality too, are those that consist of more than two writers. Of course, it is often the case that three (or more, and sometimes far more) screenwriters will work on the same screenplay, but rarely will they do so simultaneously. More often than not, “script doctors”, whose numbers have contained many of the greatest screenwriters ever from Mankiewicz to Quentin Tarantino, are called in at the last minute to try and “fix” a script that seems to have major structural problems. But far more interesting than that commonplace process are the exceptional cases where teams of three or more screenwriters have worked on the same script collectively, and thus widened or deepened it in a way that a solo screenwriter, or even a pair of screenwriters, perhaps just could not achieve.

Screenwriting teams with three members or more are far more common in the history of television writing than in the history of writing for cinema. Indeed, the process of having whole teams or groups of writers working on a single show was first established and popularised in the earliest days of television in the 1950s, particularly television comedy, when stars like Sid Caesar could command roll-calls of talent that included such future luminaries as Woody Allen, Neil Simon and Carl Reiner, who all worked at one point on Caesar’s Your Show of Shows. That is why two of the top three screenwriting teams ever are teams of TV writers and only one of them was involved in the production of a single film.

Nevertheless, the greatest screenwriting teams ever all demonstrate the potential benefit of having more than one or even two experienced and talented writers (as opposed to mere “producers”, who often yearn for a writing credit and think that “making suggestions” is the same as “writing”). Although it can be virtually impossible to establish who wrote which line of dialogue or came up with the idea for a particular scene, collectively they created something that was far greater than they would ever have created on their own. It is as if the three (or more) writers act as their own best imaginable audience, or even best imaginable critic, immediately critiquing, or even just dismissing, the ideas that only appeal to one of their number and equally quickly seizing on the ideas that excite all of them. It is a classic case of the whole being greater than the sum of the individual parts, or, as Harry S. Truman put it in praise of collective cabinet Government: “It is amazing what you can accomplish if you do not care who gets the credit.”

Of course, movies being movies, where credit on a film often determines rate of pay, screenwriters usually do care who gets the credit, and it can lead to the kind of ongoing and ultimately unsolvable feuds that have fuelled the myths (and movies) about the writing and making of Citizen Kane. Nevertheless, the point holds true generally, and certainly in the specific cases of the three screenwriting teams that I will now look at in more detail, that when it comes to story-telling many minds (or at least three minds truly working together) are often better than one.

Relevant link: you can download the screenplay for Double Indemnity here.

Double Indemnity is the film that probably has the greatest collection of sheer writing talent attached to it in cinema history, even if it is true that the three great writers involved (and there were very nearly four great writers involved with it) rarely if ever worked together simultaneously in the same time or room.

Double Indemnity was based on the novel of the same name by James M. Cain, the third member of the truly Unholy Trinity of great American crime writers of the 1930s and 1940s, alongside Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler. Indeed Cain, who may not have quite the same enduring literary legacy as Hammett or Chandler, has probably been more successful cinematically than either of his greatest rivals, in that arguably more great films have been made from his novels and novellas than from those of either Hammett or Chandler. The great Cain films include The Postman Always Rings Twice (written in 1934 and the basis of numerous English language and even non-English language films since); Mildred Pierce (written in 1941 and the basis for the classic Joan Crawford film of 1945 and more recently a TV miniseries of 2011 starring Kate Winslet); and of course Double Indemnity itself, which was written in 1943 and originally not even published as a stand-alone novel but as one of three novellas published together, two of which, including Double Indemnity, had originally been published in magazines.

Perhaps it was the fact that Cain did not rely on detectives and detective-told stories (instead, Cain tales are often told from the point of view of the so-called “criminals” who the police are hunting) as much as Hammett or Chandler did that made his tales appear so unusual in this original era of noir and crime fiction, even when compared to the works of Hammett and Chandler. Whatever the reason, the director of Double Indemnity, the great Billy Wilder, loved the original story so much that he initially wanted Cain himself to adapt it for the screen with him. However, Cain was contracted to another studio as a screenwriter and so Wilder was forced to approach another of the three great crime writers of the time, Raymond Chandler, especially when his own long-established writing partner, Charles Brackett elected not to work on Double Indemnity, because he felt that its story was too salacious.

Consequently, using Cain’s novel as their inspiration but being fully prepared to deviate it from it where necessary for cinematic reasons, Wilder and Chandler set about adapting Double Indemnity for the screen. The result was a working relationship that itself cries out to be portrayed on screen, or at least on stage, as “Billy and Raymond” repeatedly clashed over their working practices: Chandler initially believed that he would be writing alone and was shocked to discover that Wilder planned to co-write the script with him; then Chandler frequently threatened to quit, because of what he regarded as Wilder’s endless interference with his writing; and then, finally, the two men found a way to work together that actually translated Cain’s precise prose into equally precise cinematic imagery and dialogue, most importantly in the new ending for the film (one quite different to that of the original novel) that they conceived of and wrote together.

In the end, it was Wilder himself who provided perhaps the best ever explanation of why co-writing can work so successfully when he said of himself and Chandler: “If two people think alike, it’s like two men pulling at one end of a rope. If you are going to collaborate, you need an opponent to bounce things off.” They may never have worked together again, but on Double Indemnity Wilder and Chandler’s continual sparring created a war of wits and words that eventually led to the continual on-screen sparring of the supposed “lovers” in the story and their pursuer.

Relevant link: you can download the pilot script for season 1 of Frasier here.

With Friends and Sex and The City returning to TV screens soon, it is almost inevitable that the clamour for a Frasier reunion, or “reboot”, will grow too, despite the death in 2018 of one of the show’s original “Fab Five” actors, John Mahoney, who played Frasier’s irascible but none the less lovable father, Marty Crane. However, Frasier has a legacy to protect like that of no other sitcom. That is not only because the original Frasier is the sitcom that Mozart would have written if he had written comedy instead of music: one full of light and air, as well as light (and dark) opera, in addition to the requisite laughter. It is also because Frasier itself endured a terrible, indeed nearly fatal, slump two-thirds of the way through, which was only redeemed by a triumphant final series.

Frasier, of course, is the most successful spin-off show ever, as psychiatrist Frasier Crane was originally a character on the phenomenally successful Cheers (1982-1993). Unlike AfterMASH, in which some of the characters from the equally successful TV show of MASH were spun off into a series that followed their fortunes after the Korean War, or Joey, in which hapless actor Joey Tribiani from Friends became a successful Hollywood actor (if only for one season), Frasier was a smash hit that remained a smash hit for more than a decade, or at the very least for most of that decade.

Frasier was created by three of the veteran writers of Cheers, David Angell, Peter Casey and David Lee. Perhaps the most important member of this triumvirate was David Angell, who ironically was a near-lookalike for the hopeless and boorish postman Cliff Clavin in Cheers. Angell was really the figurehead of that initial trio of writers, who together came up with the idea and the set-up for Frasier, with the defining moment coming when all three writers realised that they were having “issues” with the care of an elderly relative and realised that so, too, should Frasier Crane himself. However, just as with any long-running American comedy series, they were soon complemented by the addition of other, younger writers, most notably Joe Keenan (who joined for the second season of Frasier) and Christopher Lloyd (who eventually became the showrunner, or overall producer, for Frasier).

The result was television history as Frasier became the most successful and most celebrated TV sitcom ever, winning an unprecedented Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Comedy Series for five seasons in a row in its truly imperial phase in the mid to late 1990s. And in addition to obviously working closely together on the overall arc of the show both within individual series and over the course of the whole run of the show, which soon became focused on the unrequited love of Frasier’s brother Niles for his father’s home healthcare worker Daphne Moon, individual writers wrote individually brilliant scripts that were themselves lauded. These included Joe Keenan’s first ever produced script, ‘The Matchmaker’ (the third episode of season two), in which Frasier does not realise that his new station manager is gay and so duly tries to set him up with Daphne.

Arguably, it was the death of David Angell, and his wife, on one of the planes that were crashed into the Twin Towers on 9/11 that brought the golden age or imperial phase of Frasier to an end. Certainly, there was, at least relatively speaking, a three-season slump between Niles and Daphne finally getting together and the final series in which Frasier, too, at last sought and almost found his own Daphne, in the form of a literal matchmaker called Charlotte. And most of the opprobrium of the show’s devotees for that near catastrophic tailing-off was justifiably aimed at Millicent Martin, who played Daphne Moon’s appalling (in every sense) mother, the only completely unlovable character in the show’s entire history.

However, as if belatedly honouring both David Angell and their own unique comic achievements, the remaining writers, including Keenan and Lloyd, pulled out all the stops for the final season of Frasier. They finally concentrated on Frasier’s own attempts to find a love for himself to match that of Niles for Daphne, and ended on a fittingly lofty high, not least with a final ever episode that quoted Alfred Lord Tennyson as deftly and poignantly as the first ever pilot episode had quoted the suicidal Mexican actress Lupe Velez.

Relevant link: you can download the pilot screenplay for season 1 of The Wire here.

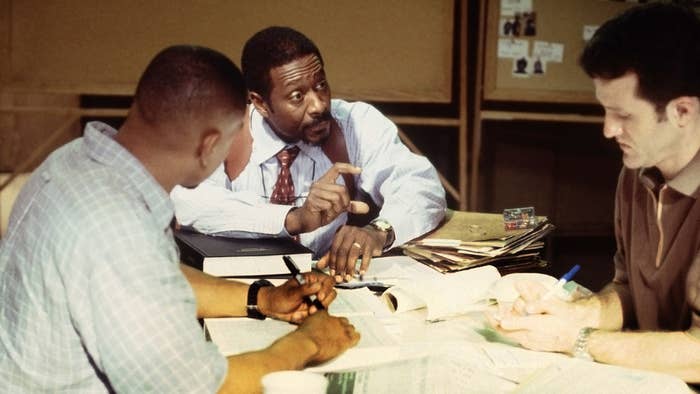

The term “Murderers’ Row” was first used not in an artistic context but in a sporting one. It was the name given to the all-conquering New York Yankees baseball team of the 1920s and in particular the first six hitters of the 1927 side, which included at least two all-time greats in Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig. More than seventy years later, David Simon, the creator and showrunner of The Wire adopted the term to describe the similarly stellar raft of talent that he had assembled for his show. It included Simon himself (who had begun his writing career as a crime reporter for The Baltimore Sun), his usual writing partner Ed Burns (a former Baltimore policeman who brought hitherto unimaginable veracity, verisimilitude and sheer fact-checking to television crime drama from his own personal experience of being a murder investigator), and three commercially successful and critically acclaimed contemporary crime novelists: Dennis Lehane (Mystic River and Shutter Island); George Pelecanos (The Cut and The Double); and Richard Price (Clockers). And the ultimate tribute that can be paid to Simon’s own “Murderers’ Row” of writers is that it was arguably even more productive in churning out great scripts than the original “Murderers’ Row” of 1920s baseball players were at churning out home runs.

As any self-respecting Wire-head (a category that should include anyone who ever aspires to write for the screen) will know, The Wire had a long and complex evolution over nearly 15 years, with its original or Ur¬ text being Simon’s own book, Homicide: A Year On The Killing Streets. Homicide was published in 1991 but actually covered the year in the late 1980s when Simon had “shadowed” or been embedded with the murder department of the Baltimore Police. Ironically, it was not so much the steady stream of deaths, drug overdoses and murders that Simon encountered in that year that first inspired The Wire as the long nights in between spent watching re-runs of Kojak, which the Baltimore detectives routinely ridiculed for its lack of authenticity and research.

Simon eventually resolved to write a realistic, indeed hyper-realistic (to the point where you could almost feel the bullets entering the bodies), account of a murder squad, which first became an award-winning book and then a TV series of the same name, Homicide, which was a cut above most cop shows on TV but still nowhere near what Simon really wanted to produce. Thus, in the late 1990s and following the extraordinary success of The Sopranos, Simon produced for HBO probably the most famous “bible” since the actual Bible, which laid out in immense detail the blueprint for a cop show that would genuinely show what life was like on the mean streets of Baltimore, not only for the cops themselves but, crucially, for the drug dealers large and small who they were attempting to capture.

The result was the TV drama equivalent of Frasier’s classic comedy, but without the slump (or jump of the shark) two thirds of the way through. In fact, The Wire only got better as it progressed, especially as Lehane, Pelecanos and Price came aboard. As with all great screenwriting teams, including those for Double Indemnity and Frasier, the writers of The Wire worked collectively to produce overall storylines for individual series and for the show as a whole, but then usually worked individually to write the scripts for individual episodes, all under the all-seeing and all-demanding gaze of Simon himself.

Unlike Frasier, The Wire did not win five Emmys in a row; in fact, most of the awards that it won were just for its final two series, seasons four and five. But ultimately it achieved something even more important. Such was the brilliance of its writing, with at least five extraordinarily talented writers coming up with plotlines and character developments through the constant generation and refining of ideas, that it contributed enormously to the TV show that is now almost universally regarded as the greatest ever made. In fact, The Wire is to television what Citizen Kane is to cinema or what the Collected Works of Shakespeare are to theatre – the work that shows to every other work in that field or genre just how much is possible, which is infinitely more than had been thought possible beforehand.

The writing of The Wire is absolutely crucial to that spectacular critical and artistic standing. In constructing his own “Murderers’ Row” of writers for the series, Simon found the crucial third element of the show, to go alongside the detailed analysis of the “Detectives’ Row” of murder police and the “Dealers’ Row” of high-ranking drug dealers they were chasing. And that collective, indeed almost structuralist, vision of writing allowed for what is probably the most authentically collective vision of a society, even an entire civilisation, that has ever been captured on any screen, in the cinema or TV.

The pandemic has surely changed screenwriting, especially team-screenwriting, as much as it has changed everything else. In particular, the vastly increased and exponentially accelerated use of Zoom and similar video-calling technologies, has enabled, for the first time ever, remote co-operative working on a scale that had previously been unimagined. Now even the humblest of screenwriters, working in geographically distant parts of the world, can work together remotely, which hopefully will provide for the kind of deeply inter-connected stories with a truly global vision that are likely to define 21st-century storytelling, both on and off the screen. If that process really comes to fruition (and it is a trend that is likely to continue even after mass vaccination hopefully brings the pandemic to an end), then we can hopefully look forward to genuinely great 21st-century screenwriting and “team-writing” in the years and decades to come.

Martin Keady is an award-winning scriptwriter whose work has been produced for film, television, stage and radio. His major credits include: The Final, a short film about the famous ending of the 1979 FA Cup Final, which was shown on Channel Four; Moon the Loon, a play about the legendary Who drummer, Keith Moon, which was premiered at The Edinburgh Festival; and a collection of love poetry, Shards, extracts from which have been broadcast on Radio Four.” http://theshakespeareplays.com/

Martin Keady is an award-winning scriptwriter whose work has been produced for film, television, stage and radio. His major credits include: The Final, a short film about the famous ending of the 1979 FA Cup Final, which was shown on Channel Four; Moon the Loon, a play about the legendary Who drummer, Keith Moon, which was premiered at The Edinburgh Festival; and a collection of love poetry, Shards, extracts from which have been broadcast on Radio Four.” http://theshakespeareplays.com/

For all the latest from The Script Lab, be sure to follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.