By Martin Keady · April 24, 2024

The term “screenwriter” has expanded in recent years to include writers for television, gaming, and all screen-based media emerging in the 21st century, such as Extended Reality or XR. Traditionally, “screenwriter” meant “writer of movies.” Today, I am focusing on the 50 greatest screenwriters in film.

These 50 writers encompass virtually the entire history of cinema and have transformed the art, craft, and language of screenwriting. Whether they wrote a series of great films or just one truly exceptional film, each deserves their place in any serious consideration of the greatest screenwriters ever. Any self-respecting screenwriter should be familiar with at least some of their work.

Billy Wilder self-identified as a writer, with his tombstone in Los Angeles bearing the words: “I’m a writer but then nobody’s perfect.” That, of course, is a reference to his most famous line, which is probably the most famous last line of any film, the two-word swansong to Some Like It Hot (1959): “Nobody’s perfect.”

While it’s true that nobody’s perfect, Wilder came closest. With his finest five films—Double Indemnity (1944), Sunset Boulevard (1950), Ace in the Hole (1951), Some Like It Hot (1959), and The Apartment (1950)—he created a full handful of classics, ranging from classic noir to the finest screen comedies ever written.

Read More: 4 Rare Screenwriting Tips from Cinema Master Billy Wilder

Billy Wilder

Woody Allen is largely a persona non grata in the film industry, but his success as a screenwriter lands him on the list of greatest screenwriters of all time. His best work is arguably Annie Hall (1977), Manhattan (1979), and Hannah and Her Sisters (1986). Even his later works like Midnight in Paris (2011) still garner accolades.

‘Annie Hall’ (1977)

Few writer-directors combined the two disciplines so successfully as Akira Kurosawa. Indeed, Kurosawa himself famously said, “If you want to be a great director, be a great screenwriter.” Above all, Kurosawa was a great storyteller.

In his films, Kurosawa created so many cinematic archetypes, from Seven Samurai (1954) to The Hidden Fortress (1958) to Yojimbo (1961), that they were invariably remade, both in Hollywood and in Europe. Only Rashomon (1950), the greatest cinematic meditation on truth-telling and its rarity, was so singular that it could not be replicated.

Akira Kurosawa

Some of the other greatest screenwriters on this list wrote entire canons, Herman J. Mankiewicz effectively wrote just one truly great film. That film, of course, is Citizen Kane (1941), which is probably the single most influential screenplay in the entire history of cinema.

Mankiewicz wrote the first draft of it, called American, and then rewrote it with Orson Welles, who also directed, produced, and starred in the final film. The precise division of their contributions will probably never be fully established, but what ultimately matters is not who wrote what but what they wrote, namely the first screenplay to have both the narrative ambition and moral ambiguity of great literature or theater. With its flashback structure famously inspired by probably the finest American novel, The Great Gatsby (1925), Mankiewicz told the story of a megalomaniac tycoon, a tale that only seems to have grown in resonance in our age of billionaires.

Fittingly, Mankiewicz became the hero of another great film when David Fincher told his story in Mank (2020).

Herman J. Mankiewicz

Fellini began his professional life as a writer, first achieving success on an Italian satirical magazine, before transplanting the comedic and convivial collaboration of magazine writing to film.

Then, for more than two decades he wrote and directed a succession of unique masterpieces that somehow combined the most intense realism with the most vertigo-inducing flights of fantasy, with his many peaks including I Vitelloni (The Layabouts) (1953), La Strada (The Road) (1954), Nights of Cabiria (1957), La Dolce Vita (1960) and 8 1⁄2 (1963), culminating in what is perhaps the greatest autobiographical film ever made, Amarcord (1973), about his childhood in Benito Mussolini’s Italy.

Federico Fellini

Fellini made southern Europe his own with his hot, feverish tales of Mediterranean life, while Bergman cinematically conquered northern Europe, especially Scandinavia, with his more austere examinations of the human condition.

Just like Fellini, he wrote or co-wrote almost all of his greatest films, and brought to life unforgettable tales of medieval plague in The Seventh Seal (1957), of family breakdown in Through A Glass Darkly (1963), and, ultimately, of individual psychological breakdown in Persona (1966).

Ingmar Bergman

Ben Hecht virtually invented the profession of screenwriter, at least in Hollywood. However, while Mankiewicz is almost exclusively remembered for writing Citizen Kane, Hecht penned numerous superb screenplays, both credited and uncredited. This was a time when credits were rarely distributed fairly, and writers who were supposed to write exclusively for one studio often collaborated with writers from other studios.

Among Hecht’s most famous credited screenplays are The Front Page (1931) and Scarface (1932), both of which were later remade at least once, and Spellbound (1945) and Notorious (1946) for Alfred Hitchcock. But, if anything, the films Hecht wrote without credit were even more remarkable. These include Gone With the Wind (1939), The Shop Around the Corner (1940), and His Girl Friday (1940).

Ben Hecht

Francis Ford Coppola was one of the greatest directors of the 1970s, having directed The Godfather (1972), The Godfather Part II (1974), The Conversation (1974), and Apocalypse Now (1979). That is surely axiomatic, but it is less widely acknowledged that he was also probably one of the greatest screenwriters of that decade. That is because, in addition to writing or co-writing the screenplays for the four masterpieces that he directed, he also wrote or co-wrote the screenplays for Patton (1970) and The Great Gatsby (1975).

Read More: Why 1974 Might Be the Greatest Year in Screenwriting

Francis Ford Coppola

The first woman to appear on this list is undoubtedly one of the greatest screenwriters ever, despite only ever writing or co-writing a total of 11 films. The relatively paltry total of screen credits, especially when compared, for example, with Ben Hecht’s estimated 100 credited and uncredited scripts, was largely due to Leigh Brackett‘s primary focus on sci-fi writing, and she was so successful in that field that she was called “The Queen of Space Opera.”

In cinema, however, Brackett deftly moved between different genres. She was one of the co-writers of The Big Sleep (1945), adapting Raymond Chandler’s great novel, and contributed to what was probably the last great film by Howard Hawks, the Western Rio Bravo (1959). Then, in an extraordinary final act as a screenwriter, she wrote or co-wrote two of the defining films of the 1970s and 1980s: The Long Goodbye (1973), which updated Philip Marlowe to 1970s Los Angeles; and the greatest Star Wars film, The Empire Strikes Back (1980).

Leigh Brackett

Just like Mankiewicz’s Citizen Kane, Robert Towne’s Chinatown (1974) is both truly historic and completely timeless, making him one of the greatest screenwriters ever.

Towne, who had already achieved considerable success with The Last Detail (1973), as well as being rumored to have contributed to The Godfather, based his magnum opus on his childhood in LA in the 1930s. Intent on writing a neo-noir that would outstrip even the original noirs by examining the complex and often unpleasant origins of the city that effectively created crime fiction, he wrote a love-hate story about LA that remains almost sadistically shocking half a century on.

Robert Towne

Emeric Pressburger probably formed one of the greatest screenwriter-director partnership in film history with Michael Powell. Their wartime and post-wartime run of films is one of the most extraordinary in film history, to the extent that Martin Scorsese, a long-time devotee of the duo, is reportedly making a documentary about them.

Pressburger’s credits include The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), the great British film about both World Wars; A Canterbury Tale (1944), a truly bizarre yet beautiful film about a mysterious man who pours glue on girls’ hair; I Know Where I’m Going (1945), one of the first and still one of the greatest romantic comedies; Black Narcissus (1947), the greatest studio creation in film history; and The Red Shoes (1948), one of Scorsese’s “Five Films To Live By.”

In short, Powell and Pressburger created one of the greatest oeuvres in English story-telling in any medium and almost certainly the greatest in English film.

Emeric Pressburger

For those directors who are not writer-directors, choosing the right screenwriter is crucial; indeed, it is so important that it often leads to the formation of great director-writer partnerships. This list examines several partnerships, particularly those involving British directors. However, few were as significant as the collaboration between David Lean and Robert Bolt in the 1960s.

Bolt had risen to fame with his play A Man For All Seasons (1960), depicting Henry VIII’s conflict with his mentor, Thomas More, which he adapted for film in 1968. However, it was with Lean that Bolt truly shone, delivering a trilogy of exceptional screenplays for Lawrence of Arabia (1962), Doctor Zhivago (1965), and Ryan’s Daughter (1970).

Robert Bolt

Credits mean a lot to screenwriters. They are often the only tangible proof of their contribution to a film, but credit is often denied them. However, the greatest “credit theft” in film history is surely that which Ruth Prawer Jhabvala suffered. That is because she was the third and effectively silenced partner of one of the greatest and most commercially successful film-making partnerships of all time, Merchant Ivory.

Although producer Ismail Merchant and director James Ivory got their due, their go-to screenwriter was never given the third billing she deserved despite writing almost all of the greatest Merchant-Ivory films: Shakespeare Wallah (1965), A Room With A View (1985), Howards End (1992), and The Remains of the Day (1993).

Ruth Prawer Jhabvala

With all due respect to Robert McKee, William Goldman stands out as the greatest screenwriter who transitioned into a prominent screenwriting guru after publishing his memoir, Adventures in the Screen Trade (1983). This memoir stands as the greatest (and certainly the most commercially successful) book about screenwriting ever.

Goldman’s authority stemmed from his own experiences, having won two screenwriting Oscars: the first for Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969) and the second for All The President’s Men (1976). Additionally, Goldman penned many other notable films, including Marathon Man (1976) and The Princess Bride (1987), both adapted from his own novels.

William Goldman

Before Ruth Prawer Jhabvala won screenwriting Oscars in successive years for Howard’s End (1992) and The Remains of the Day (1993), it had been over half a century since a female screenwriter had won back-to-back Academy Awards for writing.

Prawer Jhabvala’s predecessor as a serial Oscar-winning woman screenwriter was Frances Marion, one of the most successful writers of “talkies,” as cinema completed its most important technological and conceptual transition, from silence to sound. Marion won her two Oscars for The Big House (1930) and The Champ (1931), the earliest and best boxing film of that name.

Read More: 10 of the Best Scripts Written by Women

Frances Marion

In Hitchcock’s golden age, he employed a succession of great screenwriters, but the greatest of them was Ernest Lehman. For Hitchcock, Lehman wrote North by Northwest (1959), somehow wrestling into a story Hitchcock’s long-nurtured but nebulous idea about a man trapped on Mount Rushmore (the original working title for the film was The Man In Lincoln’s Nose).

Yet Lehman had already contributed to a non-Hitchcock classic in Sweet Smell of Success (1957). And as Hitchcock declined in the 1960s, Lehman rose above his old master by becoming the writer for many of the greatest Hollywood musicals of that decade, including West Side Story (1961), The Sound of Music (1965), and Hello Dolly! (1969), while somehow still finding time to adapt Edward Albee’s generational play, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966).

Ernest Lehman

No one has done more to reinvent cinematic language in the last 30 years than Quentin Tarantino, given that his distinctive kind of pop-culture-quoting wisecracking dialogue has become almost ubiquitous among his many imitators in the 1990s and early noughties.

Tarantino has been a spectacular screenwriter, especially in his first two films, Reservoir Dogs (1992) to Pulp Fiction (1994). There are very few writers, or even writer-directors, since Tarantino who have earned their own equivalent of “Tarantino-esque” to suggest a writer or writer-director with a unique and complete worldview, and the dialogue and plotting chops to go with it.

Read More: Screenwriting Advice from a Young Quentin Tarantino

Quentin Tarantino

Raised by a strict Calvinist father, Paul Schrader barely saw any films at all when he was a child. When he left home to attend college, he immersed himself in them, particularly those that resonated with his ultra-orthodox upbringing.

Like so many of the French New Wave writers and directors, Schrader was a classic gamekeeper turned poacher, graduating from writing film criticism to writing screenplays. He wrote The Yakuza (1974), Taxi Driver (1976), and Raging Bull (1980).

Paul Schrader

Paul Schrader was supplanted as the most famous living screenwriter at the start of the 21st century by Charlie Kaufman, a screenwriter who attained the fame of a director (if only temporarily), for creating seemingly scattershot, stream-of-consciousness scripts that were always grounded in a powerful central idea.

Being John Malkovich (1999), in which ordinary people got to experience 15 minutes of fame before being ejected onto the New Jersey turnpike, and Adaptation (2002), in which Nicolas Cage played a pair of screenwriting twins trying to adapt for cinema a seemingly unadaptable book, were fascinating explorations of fame and obsession.

But Kaufman’s masterpiece is undoubtedly Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004), which crystallized all of his ideas about memory, storytelling, and movies.

Read More: Being Charlie Kaufman: The Self-Consciousness of Absurdist Comedy

Jessie Buckley & Charlie Kaufman behind the scenes of ‘I’m Thinking of Ending Things’ (2020)

Joel and Ethan Coen wrote their films together, making them one of the greatest screenwriting teams. Avowed movie lovers, the Coen brothers’ specialty has always been to take existing genres and somehow turn them inside out or shock them back to life, with electrifying writing. This was evident in their still-sublime debut, Blood Simple (1984), which is simultaneously one of the great noirs and one of the great neo-noirs.

They maintained their dizzying reinvention of cinema through a multiplicity of genres and sub-genres: the screwball comedy in Raising Arizona (1987); gangster movie in Miller’s Crossing (1990); screenwriter noir in Barton Fink (1991); and the almost sui generis The Big Lebowski (1998), whose main character, the Dude, is probably the most beloved movie character of the last thirty years.

Read More: The Dudes Abide: The Must-Read Scripts of the Coen Brothers

The Coen Brothers

Julius and Philip Epstein are the second set of screenwriting brothers to make this list. And there is no doubting the screenwriting ability of the Epsteins because, along with Howard Koch, they were the writers of Casablanca (1942).

Unsurprisingly, Casablanca was almost impossible to top and it remains the sole major credit for the twins because Philip died of cancer a decade later. Julius continued to write alone, but it was arguably only until 40 years after Casablanca that he came close to equaling it with Reuben, Reuben (1983), a hilarious, painful, and only thinly disguised biopic of Dylan Thomas as he “spread a picnic on the precipice.”

The Epstein Brothers

While Hollywood has largely cornered the market in screenwriters (especially in English), there have been screenwriters from other, non-US film industries that have attained the fame or status of a Hecht, Lehman, or Schrader. One of those is Jacques Prevert, arguably the greatest French screenwriter (in addition to being a celebrated poet).

Prevert wrote many French films over more than three decades, but two absolute masterpieces stand out even in a fairly stellar list. Le Crime de Monsieur Lange (1936) was one of Renoir’s mid-career classics in which an unsuccessful writer becomes his own publisher (when the publisher runs off with the firm’s money) and then has to confront the villainous publisher when he returns.

The second, Les Enfants du Paradis (1945), is an even greater achievement because many, including Francois Truffaut, regard it as the greatest film ever made. Marcel Carné’s masterpiece about French survival during WW2, is told through the tale of a theatre company in Paris in the 1890s.

Jacques Prevert

The incredible life and career of Dalton Trumbo were worthy of a biopic, so it is entirely appropriate that, to date, he remains one of only two Hollywood screenwriters (alongside Mankiewicz) to have had his life turned into a movie.

Trumbo experienced a remarkable journey, transitioning from being the most commercially successful screenwriter in history, with early hits like Johnny Got His Gun (1939), to becoming the most famous blacklisted writer/director in the early 1950s. Despite writing under pseudonyms for films such as Roman Holiday (1954) and Spartacus (1960), he later enjoyed an extraordinary third-act revival, a turn of events that even a writer as cynical as Trumbo himself might have deemed unbelievable.

Dalton Trumbo

Jay Presson Allen was probably the finest and certainly the most commercially successful female Hollywood screenwriter of the 1960s and early 1970s. She almost literally sprang to fame and fortune after Alfred Hitchcock hired her, on the back of her successful Broadway adaptation of Muriel Spark’s novel The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (1961), to write Marnie (1964).

Marnie may have marked the end of Hitchcock’s career, but it was the launchpad for Presson Allen, who went on to adapt The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (1969) for cinema before her greatest triumph, the screenplay for Cabaret (1972)

Read More: The Top Ten Female Screenwriters of the 70s and 80s

Jay Presson Allen

Paddy Chayefsky completes the Holy Trinity of great American screenwriters who have each won three screenwriting Oscars, even if Chayefsky is not nearly as well-known as Wilder or Woody Allen because he was purely a screenwriter rather than a writer-director. Nevertheless, Chayefsky could claim one thing that neither Wilder nor Allen could, namely that he triumphed not just in film but in film and television. Indeed, Chayefsky was arguably the first great television writer, especially with Marty (1953).

It was only in Chayefsky’s later years that he recaptured his ’50s fame with a couple of very different but equally stunning screenplays. The first was Network (1976), his great howl against the increasing stupefaction of America and by extension the Western world. And the second was Altered States (1980), a hallucinogenic, indeed phantasmagorical exploration of drug culture.

Paddy Chayefsky

Jean-Claude Carrière was the successor to Prevert as the go-to screenwriter of the French film industry, writing or co-writing a number of late 20th-century classics. He found a great director to write for in Luis Buñuel, writing Belle de Jour (1967) and The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972).

After Buñuel, Carrière wrote for a succession of European and American directors, including for Volker Schlöndorff in The Tin Drum (1979), and for Philip Kaufman in The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1988).

Jean-Claude Carrière

Bruce Robinson achieved the status of one of the greatest screenwriters ever with his first two screenplays, The Killing Fields (1984) and Withnail & I (1987), which remain, nearly 40 years on, probably the greatest debut and second or sophomore screenplays ever written. Having recently contributed to a new book about the film, Withnail and I: From Cult To Classic (2023), I can personally testify to the enduring genius of the screenplay for Withnail & I.

Bruce Robinson

Unlike the Coens and the Epsteins, Herman J. and Joseph L. Mankiewicz did not write together. The older brother Herman was already a celebrated screenwriter by the time the younger brother Joseph arrived in California. Indeed, one could go further and say that it was only when Herman’s star began to wane that Joseph’s star began to rise.

Joseph achieved a remarkable one-two trick, winning the Oscar for Best Director and the Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay in consecutive years with A Letter to Three Wives (1949) and All About Eve (1950). Later in his career, Joseph wrote and directed Julius Caesar (1953), Guys and Dolls (1955), and Cleopatra (1963).

Joseph L. Mankiewicz

In the late 1980s and 1990s, Nora Ephron was the most famous female screenwriter in the world, with a succession of scripts, usually told from a female perspective, that included arguably the greatest rom-com of the late 20th century.

After the end of her marriage to Watergate reporter Carl Bernstein, Ephron began to write screenplays, starting with Silkwood (1983), then adapting her novel/thinly disguised autobiography, Heartburn (1986). But Ephron’s masterpiece was to come with When Harry Met Sally (1989).

Nora Ephron

Aaron Sorkin is probably the most famous writer of dialogue in recent decades, with the simultaneously detailed but messy exchanges in The West Wing (1999-2006).

Having originally made his name as one of the greatest screenwriters with the screenplay for A Few Good Men (1992), Sorkin mainly worked in TV before returning spectacularly to film with The Social Network (2010).

Read More: My Walk and Talk with Aaron Sorkin: A Month in Aaron Sorkin’s Master Class

Aaron Sorkin

Billy Wilder wrote both of his inimitable double-bill of screen comedies, Some Like It Hot and The Apartment, with his second great co-writer, I.A.L. Diamond. For two men to have written such equally fabulous but completely different comedies—the first being the screwiest of screwball comedies and the second being arguably the most dramatic comedy ever written—is almost unbelievable.

Perhaps inevitably, Wilder and Diamond could not top that spectacular double-hitter, but they continued to write together for many years, achieving perhaps their next biggest success with the delightful The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes (1970).

I.A.L. Diamond

Wilder’s first great co-writer was Charles Brackett. Wilder and Brackett met while helping to co-write Ninotchka (1939), and almost instantly hit it off as writers, if not necessarily as friends; the idiosyncratic émigré Wilder and the ultra-patrician Brackett were very different temperamentally.

Nevertheless, they made some of Wilder’s earliest classics together: The Lost Weekend (1945) and Sunset Boulevard.

Charles Brackett

Graham Greene was among the greatest novelists of the 20th century but he was also among its greatest screenwriters. Having begun his career in film as a critic before getting into trouble for suggesting that child star Shirley Temple’s biggest fans were “middle-aged men,” Greene eventually stopped writing about movies and started writing them.

Like so many European filmmakers, his screenwriting career boomed after WW2, first with the screen adaptation of his novel Brighton Rock (1948). Other notable films of his include Fallen Idol (1948) and The Third Man (1949).

Graham Greene

The second truly great writer in another medium to appear on this list of the greatest screenwriters is playwright Harold Pinter. Pinter may be most famous for his plays (and the pauses in them), but he had grown up during the Century of Cinema and always loved film, which eventually led to his writing a series of excellent screenplays for Joseph Losey.

The two men made three superb films together: The Servant (1963), Accident (1967), and The Go-Between (1971).

Harold Pinter

Shinobu Hashimoto was one of Kurosawa’s principal co-writers, especially during the 1950s when Kurosawa created an alternative cinematic world in the East to go alongside Hitchcock’s cinematic domination of the West.

Among the films that Hashimoto co-wrote with Kurosawa are arguably Kurosawa’s two greatest films: Rashomon and The Seven Samurai. He also wrote or co-wrote many other fine Japanese films, including Sword of Doom (1966)

Shinobu Hashimoto

One of the greatest screenwriters from London is T.E.B. Clarke. He may not be as well known as many other screenwriters, but his work remains world-famous. That is because he was the principal writer for Ealing Studios, which became the only film studio, rather than its far bigger US counterparts, to give its name to an entire genre: “Ealing Comedies.”

Clarke wrote or co-wrote many of the greatest Ealing comedies, like Passport to Pimlico (1949), The Lavender Hill Mob (1951), and The Titfield Thunderbolt (1953).

Read More: 10 Famous Screenwriters from London

T.E.B. Clarke

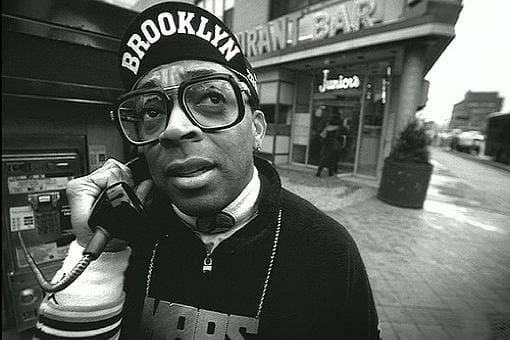

Spike Lee remains one of the greatest screenwriters/directors working in Hollywood. At the start of his career, Lee also acted, playing one of the love interests in his beautiful black-and-white debut, She’s Gotta Have It (1986) and the lead in Do The Right Thing (1989).

More recently, Lee wrote and directed another classic in BlacKkKlansman (2018), which told the unbelievable but true story of a black policeman in the 1970s who somehow infiltrated the Ku Klux Klan.

Read More: 5 Trademarks of a Spike Lee Script

Spike Lee

Tullio Pinelli was to Fellini what Shinobu Hashimoto was to Kurosawa, namely the great co-writer who helped a great writer-director to complete their scripts.

Fellini worked with many co-writers, including at least one other great writer-director, Pier Paolo Pasolini. However, it is Pinelli whose signature is most prominent among them, including on La Strada, La Dolce Vita, and 8½, which is one of the greatest films ever made about the wholly mad business of filmmaking.

Tullio Pinelli

Elaine May initially wrote and performed with her husband, Mike Nichols, before she emerged as a superb writer/director in her own right, first with A New Leaf (1971), then with Mikey and Nicky (1976) before co-writing (with Warren Beatty) Reds (1981), a remarkable account of the Russian Revolution.

Elaine May

Greta Gerwig‘s opening run of films—Lady Bird (2017), Little Women (2019), and Barbie (2023)— is probably the finest in Hollywood since Rob Reiner’s first six superb films in the late 1980s and early 1990s, cementing her place as one of the greatest screenwriters in modern cinema.

The “double ending” of Barbie in particular, in which the titular doll first contemplates the reality that being alive is necessarily painful before ending with one of the best jokes in recent cinema, is a testament to Gerwig’s brilliance as a writer and director.

Read More: 6 Things Greta Gerwig Learned About Writing from Being an Actress

Greta Gerwig

William Goldman, the most commercially successful screenwriter and screenwriting guru of the 1970s and 1980s, is barely remembered now, so it is not surprising that the “Second Screenwriting Goldman,” Bo, who was no relation to William, is so little celebrated today.

Nevertheless, between them “The Goldman Boys” wrote many of the greatest films of the 1970s, the last truly great decade of American film. In particular, Bo wrote three masterpieces that form his own Insanity Trilogy: One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975), Melvin and Howard (1980), and Shoot The Moon (1982).

Bo Goldman

Like some of the other greatest screenwriters on this list, Phyllis Nagy’s reputation largely rests on one great screenplay, Carol (2015). The film, based on a Patricia Highsmith novel, depicts a love affair in the early 1950s between a younger single woman and an older married woman, who ultimately faces losing her children if she continues the affair.

‘Carol’ (2015)

As unforgettable as “Diablo Cody” is as a nom de plume, it is not the greatest creation of Brook Busey; that is Juno (2007), which more than 15 years on remains the gold standard of teen comedies.

While it is true that Juno remains probably the only great screenplay that Cody has written—notwithstanding the multiple pleasures of Young Adult (2011) and Tully (2018)—it is such a singularly brilliant script that its singular brilliance merits its author’s inclusion in this list of the greatest screenwriters.

Diablo Cody

David Williamson is one of the greatest screenwriters to hail from Australia. He was a successful writer for film, TV, and theater in the 1970s, but it was his Australia Trilogy—Gallipoli (1981), The Year of Living Dangerously (1983), and Phar Lap (1983)—that launched him (and to a degree Australian cinema) on the world stage.

David Williamson

Like so many of the greatest screenwriters and directors, Chloe Zhao began her career in film by writing and directing short films, including The Atlas Mountains (2009).

Zao graduated to features with Songs My Brother Taught Me (2015), a drama–if not tragedy–about life on a Native American reservation, and her second feature, The Rider (2017), had a similar setting and a similarly moving story about a former rodeo rider trying to recover from a serious fall. However, it was her third feature, Nomadland (2020), that launched Zhao into the cinematic stratosphere.

Read More: Celebrating the Best Screenplays by AAPI Writers

Chloe Zhao

Woody Allen has worked with a number of co-writers over the years, but the greatest by far is Marshall Brickman. Brickman first worked with Allen on Sleeper, but it was when Allen began to make more serious and dramatic films that Brickman became his perfect writing partner.

With Annie Hall and Manhattan, the former a dazzlingly inventive comedy about the end of a love affair that seemingly employs every cinematic trick in the book (from direct-to-camera address to animation) and the latter a more “classical” black-and-white meditation on love in NYC, Allen and Brickman created the greatest comedy double-bill since Billy Wilder and I.A.L. Diamond wrote Some Like It Hot and The Apartment, nearly twenty years earlier.

Marshall Brickman

Gillian Flynn has been one of the most successful female screenwriters of the last decade, despite having only two co-writing credits to her name: Gone Girl (2014) and Widows (2018).

Gillian Flynn

Lynne Ramsay is the Scottish writer-director who has followed in the tradition of Alexander Mackendrick and Bill Forsyth by creating cinematic worlds that are simultaneously utterly Scottish and universal, at least in her first couple of films: Ratcatcher (1999) and Morvern Callar (2002).

Ramsay’s second set of films has been much bigger and grander in scale: We Need to Talk About Kevin (2011) and You Were Never Really Here (2017).

Lynne Ramsay

As a black lesbian filmmaker, Dee Rees is almost the embodiment of intersectionality, namely the concept that it is the interconnected nature of social categorizations such as class, race, or sexual identity, especially as they apply to an individual, that reflects the true nature of so much social oppression in the 21st century.

Pariah (2011), Mudbound (2017), and The Last Thing He Wanted (2020) prove that Rees is one of the greatest screenwriters.

Dee Rees

The final entry on this list is the first screenwriter, Georges Melies, who wrote what is generally regarded as the first screenplay ever written, for his silent classic Le Voyage dans la Lune (A Trip to the Moon) (1902).

Although Melies’ screenplay had no dialogue and consisted mainly of “directions” (both for Melies the director and his cast), it is still seen as the document that established the template for screenwriting.

Read More: The 10 Best Short Films Ever Made

Martin Keady has written for The Script Lab for nearly a decade. He has also contributed to WITHNAIL & I: FROM CULT TO CLASSIC, a new book about the most quotable film ever made, and written SHAKESPEARE, the first ever biopic of the Bard.